Dennis Lehane Has Many More Boston-Based Novels Lined Up

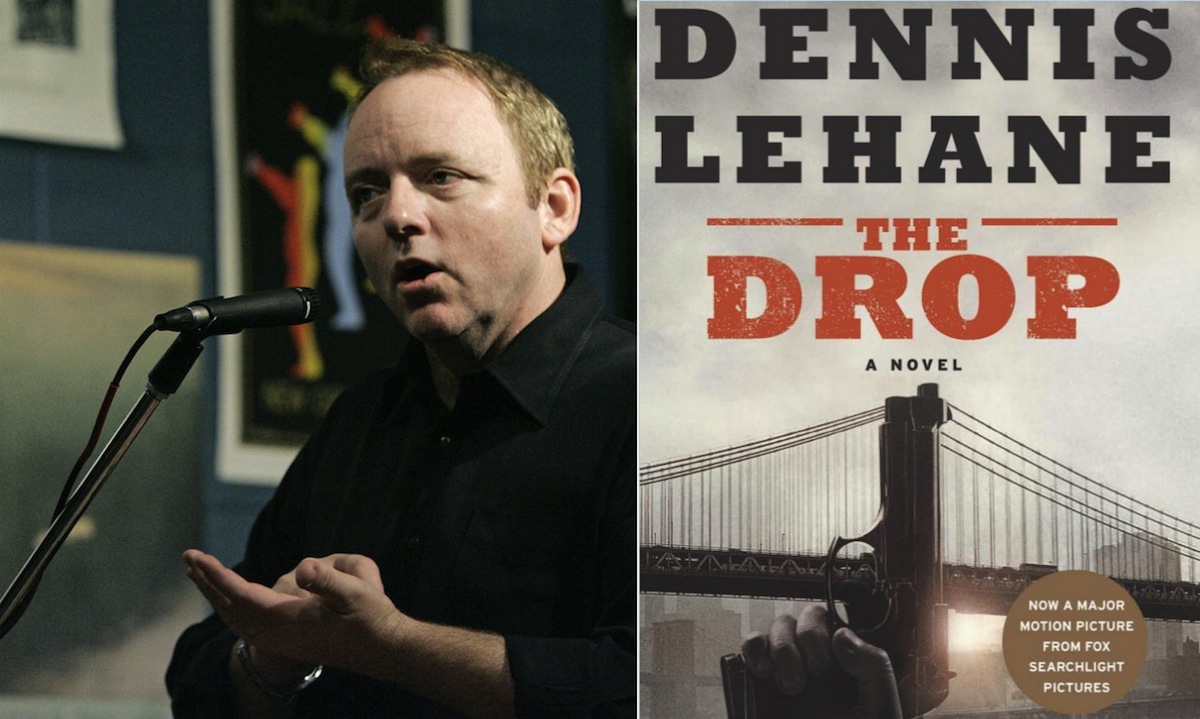

Image via Associated Press/Dennis Lehane

Long before Dorchester-bred author Dennis Lehane announced the official release date of his new book, The Drop, which features a scene where the novel’s protagonist discovers an abandoned puppy inside of a trash can, fans of his noir-style works feverishly wondered if the anecdote was the manifestation of true life events that transpired in December 2012, when the Lehane’s family beagle, Tessa, suddenly vanished from their Brookline home.

Spoiler alert: it’s wasn’t.

In fact, the scene was derived from a short story called Animal Rescue that Lehane created years ago, which was based on a failed attempt at a novel that he started to write more than a decade before Tessa sadly disappeared.

“That whole thing—it was not remotely connected. It’s just been a weird thing in my life,” Lehane said in an interview.

In early September, Lehane’s newest work of fiction will hit bookshelves just days before a movie-version hits theaters. The film stars big-name acts like Tom Hardy, known best for his role as the sinister villain in 2012’s Dark Knight Rises, and The Sopranos’ James Gandolfini, who passed away last year, in his final on-screen role.

Lehane, whose writing is often centered on Boston and features a cast of gritty characters living in the city’s underbelly, took a different approach to coming up with the book version of The Drop. Instead of writing it and then having it optioned to become a film, Lehane first penned the script for Hollywood hotshots, and then later went back and wrote the novel based on that screenplay.

Here, Lehane talks about why that particular process was refreshing for him as an author, and what he has on tap next for bookworms looking for more crime-centric reads.

Are there any big differences between the book and the film?

[The book] just goes deeper. Structurally, it’s the same. It just goes—all the stuff that got left on the cutting room floor, a lot of stuff that got cut out of the script; there’s a lot of stuff that came from the original source material that I never used, and a lot of stuff I wanted to go deeper on. It enriches the experience.

The setting is different, too.

Yes. The book is in Boston, the movie is Brooklyn.

Was that out of your hands in terms of location choice?

In terms of the movie, yes. There was a point where they came to me and said, ‘we really just don’t want to do another, you know, white criminals in Boston movie.’ I said fair enough. It’s sort have been a little bit beaten down in the first 10 years of the 2000s. So they said let’s do Brooklyn, and that was great visually. I was all 100 percent supportive of that decision. But when my publisher approached me about writing a novel [based on the screenplay for the movie], and I had always seen it as taking place in the same neighborhood of Mystic River, I said, ‘I will never set this in Brooklyn.’ It just feels like this is a little bit my turf. When I write a book, I want to set it in Buckingham, which is a world I created [within Boston]. It just felt right. It also felt—because there have been many incarnations of this story—it started as a failed novel, and then I culled from that novel a short story, and then the story got optioned and became a script, and the script became a novel.

That’s quite a different process for writing a book.

It is. It was really fun and actually really cool. The original incarnation of it, when I started it with a novel, that was set in Buckingham. That was in 2002. That became the short story Animal Rescue, and then that got picked up for the movie.

And you even wrote the script for the movie.

Right, I wrote the script. There was nobody else who had their hands on the script at all.

How was it writing that?

It was great. It was a really wonderful experience because nobody had any illusions about the type of movie we were trying to make. Everybody was always on board to kind of make a gritty, down-and-dirty, 1970s-influenced film. The commercial considerations didn’t override the film. We didn’t say, ‘oh, we have to slap on a happy ending,’ or ‘oh, we have to do this because market research.’ We knew what we were making with really terrific actors.

Including James Gandolfini.

Yes. This is it. This was his final film.

Did you have a chance to work with him on set?

No. It’s really sad. We played phone tag a bunch early on, and then I was on set, but he wasn’t shooting. But we were psyched because we were going to meet that night for dinner, and he was going to come, and then he couldn’t make the dinner. But I’ll never forget it: he sent over six bottles of wine as an apology—a really nice note. He’s just a really classy guy. But we never—to my everlasting regret—I never met him.

That’s too bad. But it’s pretty great that he starred in a film based off of a script that you wrote.

It is. It’s fantastic. And I was the biggest cheerleader for that. I wanted him cast, and there was a lot of going back-and-forth, and a lot of other actors interested in the part. It became something a lot of big names wanted to play, but I was always in the background going, ‘Gandolfini, Gandolfini, Gandolfini.’

I read somewhere that you like to see movies first and then read the books. How did that play out for you personally in writing this script, and then the novel based on this script?

It’s weird; it’s the same thing. You get to do things you didn’t get to do in the script. You get to do things with language, you get to spin a sentence, or you can take a paragraph and say, ‘let me paint a picture here.’ It’s the literary things that I like to do. And also, you just get to go deeper. You get to do things that never show up in a screenplay. They’re different forms…cinema is image-driven, and literature is word-driven. The best example is the ending of Gone, Baby, Gone. The ending of the book is a literary ending, in the sense that it’s all in somebody’s head. But Ben [Affleck], when he makes the film, can’t do that. So he came up with this beautiful image of the main character and this little girl sitting and watching this TV. They watch the TV in the book, but it’s not in the ending…in both cases, they are wonderful endings, but they are different [in what they do].

Since we’re talking about Gone, Baby, Gone, I have to know: are they going to do a movie on the sequel, Moonlight Mile?

It was in the works for a TV show, and got all the way up to—we were hiring writers, and then it collapsed. So I don’t know. I think the idea of a TV show was kind of working. The thing is, Gone, Baby, Gone, as a film, it wasn’t financially successful—it’s a great film we are all so deeply proud of—but it was not financially successful, so nobody is making a sequel to it.

Even so, it’s one of those films like Shawshank Redemption. When it’s on TV, you have to watch it.

Is it really? That’s cool to hear. I had no clue. It’s funny, because it’s the only film of my books that for some reason I can really watch to this day. Like if I come across it, I’ll watch it for a bit.

You can’t do that with Mystic River?

No. I feel weird. It’s a weird out-of-body experience. You know what it is? It’s like how you feel when you hear your voice. It’s that feeling times a thousand.

Shifting gears a little bit here. One of the parts in The Drop—the movie and the book—there’s a whole thing with the lost puppy, and the relationship with the puppy. Has anyone asked if it has to do with your missing dog?

You know, people brought it up when my dog went missing. There was one point where there was a thread [online] that said it was a publicity stunt to call attention to the The Drop. Believe me, if I knew when I wrote the first scene of this book, which became the first scene of the short story, which became the first scene of the film, about a guy finding a dog two days after Christmas in a trash can—and I wrote that in 2001—if I knew that [years later] my dog would disappear near the same day, that would have freaked me out too.

Did it freak you out when Tessa went missing?

It did. It was too weird. It was like, ‘what the fuck,’ to be honest with you. That whole thing—it was not remotely connected, though. It’s just been a weird thing in my life. It’s like how everybody thinks my wife, Angie, is the basis for Angie [Gennaro from Gone, Baby, Gone]. No. I met her years, and years, and years after I created the character. My life is filled with those [coincidences] actually. But the one with the dog is easily one of the weirdest of all time.

Did you ever end up getting a new dog?

We got another rescue, but we never found Tessa. There was just—at some point you had to believe that, basically, whoever took her knew. She had to have been taken, because there were too many eyes on those streets where she vanished. It wasn’t just—it was my wife and these wonderful, incredible strangers who searched for her in the freezing cold. It was a humbling experience to be honest with you.

What do you think happened?

I think she vanished that night, on Christmas Eve, and my feeling is she probably jumped in a car. This is my theory because the last place she was seen was at a McDonald’s in Allston. I think she jumped in a car, and they said, ‘hey, I would like to give this dog to my sick mother, or my son,’ or whatever it is, for Christmas. Once word got out, they weren’t going to turn around and take the dog back. So that’s what I always thought happened.

Hopefully she’s OK.

Yeah, I just hope she is happy. That’s all we care about.

You’re also working on the last installment of the Coughlin-family series, which is due out in March. What comes after that?

I just want to…start writing books based in Boston again. There’s a trilogy planned—sort of Drop-size novels—because I really fell in love with that voice again, and I want to really write more about Boston in that voice. That’s the next round of books, and I’m still very much turning it all over in my head. But that’s the next round.

Do you come back to Boston to get back into the mindset and find that voice?

I don’t need to. It’s so burned into my brain. I don’t need to do any of that. I’ll check archives for various things, though. I don’t live in Boston right now, and that makes me ridiculously homesick. And when you are homesick, you write way better about the place you are missing. It becomes so much more vivid. You don’t write about summer in the summer, you write about summer in the winter, and you’ll be amazed by what details come back to you. You get more vivid and rich, and you put it down on the page better, I think. That’s why I’m not concerned at all about my ability to tap into Boston.

Editor’s note: This interview has been formatted and condensed.