Stephen Sondheim Thinks Getting Rid of Boston’s Colonial Theatre Would Be ‘A Crime’

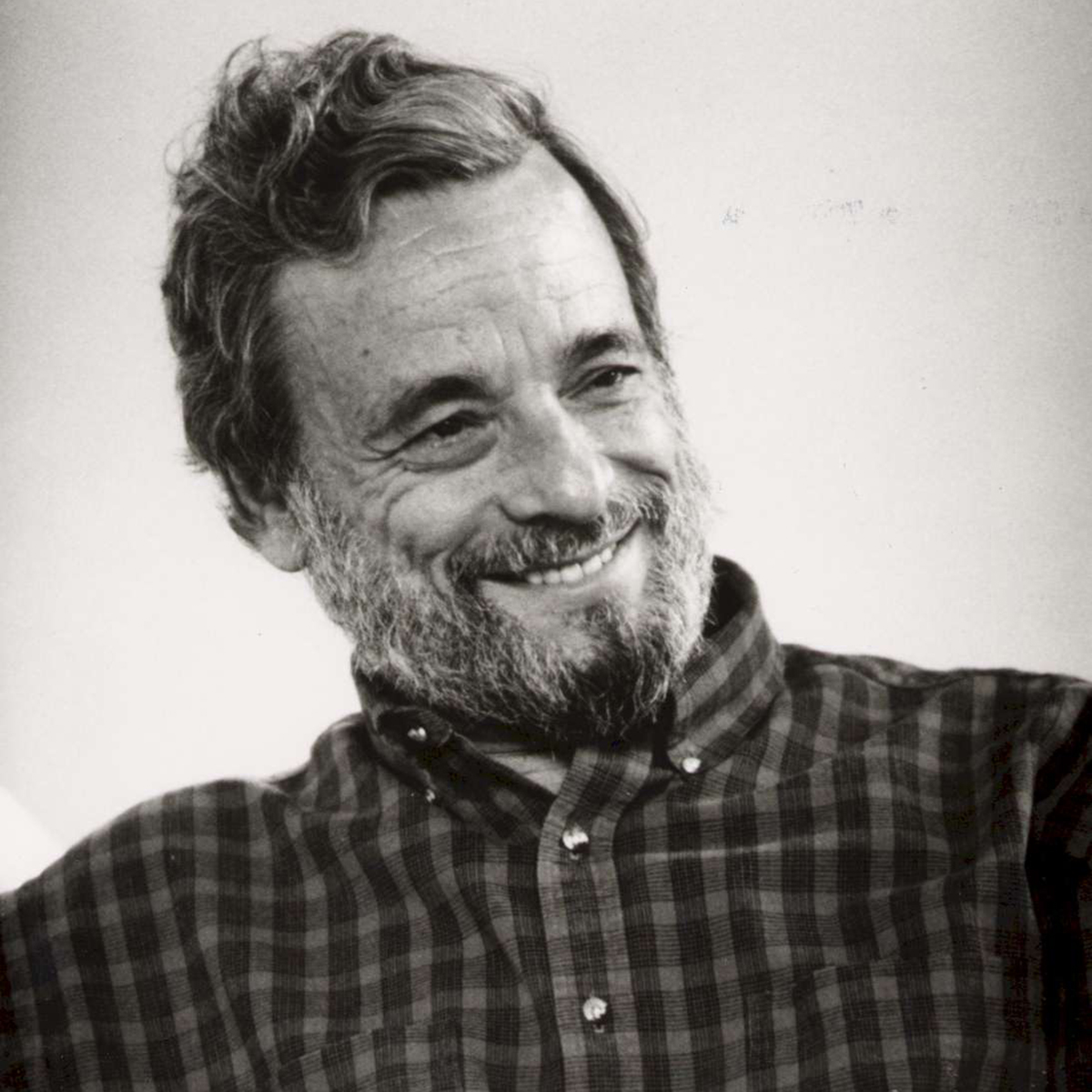

Photo by Alex Lau

In a word, Stephen Sondheim says it’s a “crime.”

He’s talking about Emerson College’s proposed plan to repurpose the fabled Colonial Theatre as a student activity center, with a cafeteria in an adjoining building and dining tables in the orchestra section.

“I’ve had shows which tried out in the Colonial, and it’s not only beautiful but acoustically first-rate, two qualities which are rare in tandem, even on Broadway,’’ Sondheim told me this week. “For those of us involved in musical theater, it’s a treasure and to tear it down would be not only a loss, but something of a crime.”

Sondheim knows his way around crime. The man with the acid pen has composed musicals about presidential assassins and a barber who turns into a butcher of squires and priests. And Sondheim, who is known as nothing short of God in theater circles, has a long history of opening pre-Broadway tryouts at the Colonial, Boston’s oldest continually running theater. He tried out Follies there in 1971 and A Little Night Music in 1973. Ethel Merman starred in Gypsy back in the day, and the first national tour of Into the Woods opened at the Colonial.

Granted, Emerson is not planning to tear down the theater. That wouldn’t be possible anyway, since a petition to landmark the theater has been pending with the Boston Landmarks Commission for, oh, about 25 years. Any changes to the theater must go through the Commission’s Accelerated Design Review process, and Emerson has not initiated that process. Last week, Emerson President Lee Pelton told Boston that the college is exploring many options for the historic showplace, with the dining space being just one possibility. But he didn’t provide details on the other plans.

The Colonial Theatre Building, Hotel Touraine, and Masonic Building in 1903. / Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The plan for the student center, however, has elicited a local and national outcry. More than 6,000 people have signed a change.org petition titled “Tell Emerson the Colonial Matters.” Sondheim’s name has been invoked frequently by signers of the petition, including stagehands, actors, Emerson students and faculty members, and folks who remember seeing shows at the grand old dame. Former New York Times critic Frank Rich sent a shout-out to Sondheim on the petition and on Facebook—with a particular mention of Follies, which takes place in a theater that is about to be torn down. “It is astonishing that Emerson College, which thinks of itself as an institution furthering the arts, would be preparing to deface the Colonial Theater in Boston,” Rich wrote. “What Emerson is planning to do to the Colonial is an egregious example of life imitating art.”

Ted Chapin, president of the Rodgers and Hammerstein organization and the author of Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’ signed as well. He was just a college kid working as a production assistant when Follies tried out in Boston, and he has fond memories of the place where Rodgers and Hammerstein rewrote and renamed Oklahoma in the theater’s ladies’ lounge. “It is probably one of the most historically important theaters in the country,’’ says Chapin, who remembers seeing the pre-Broadway tryout of Hallelujah, Baby! there when he a tyke.

It’s unclear what other options Emerson is considering for the Colonial, which has remained dark for much of the last few years. But last year’s Broadway season broke box office records, and there is theatrical product out there that could play the Colonial. The recent six-week run of Book of Mormon brought in millions of dollars and could have sat for many more weeks. I was there on the last day of the run, and there wasn’t an empty seat in the house.

The Emerson board of trustees is set to meet next week to discuss, among other things, the future of the theater. It’s a little more than obvious that the powers that be underestimated the local and national community’s attachment to the theater and its history. Somehow, they missed that day of class.

Meanwhile, Sondheim, at 85, is squirreled away working on a new musical, a collaboration with David Ives that is based on two films by the Spanish director Luis Bunel. The man who once penned a fiery letter to the Times protesting Diane Paulus’s production of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess said he didn’t have time to say much more than he told me in an email. But he did add, “I signed the petition, of course.”

Stephen Sondheim photo via The Huntington on Flickr/Creative Commons