A Local Artist Used Van Gogh’s DNA to Replicate His Ear

Sugababe photo provided to bostonmagazine.com

Arguably rivaling the notoriety of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings is the story of his own ear, legendarily lobbed off in 1888.

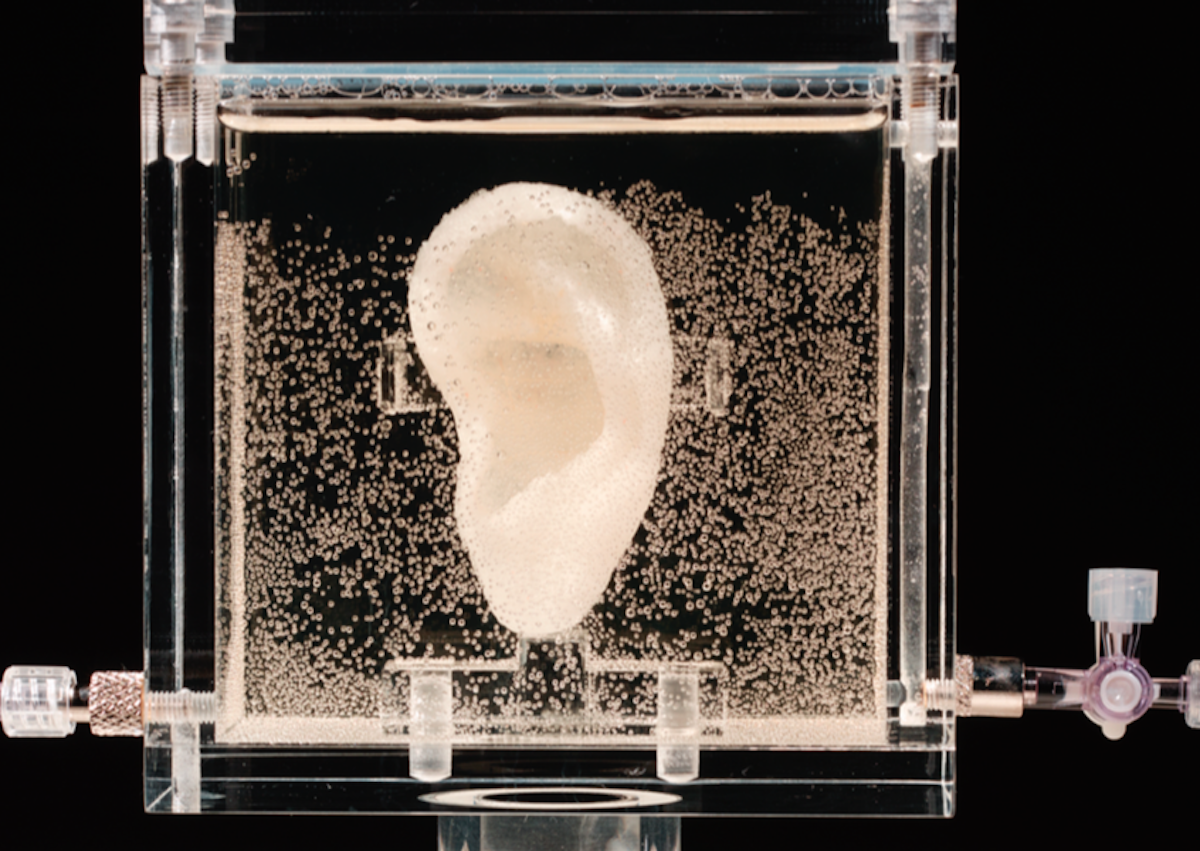

This year, cutting-edge genetic engineering and cloning technology has allowed the infamous ear to be lifted from history and re-purposed as modern art. Local concept artist Diemut Strebe created a living replica of van Gogh’s ear from tissue-engineered cartilage, a piece she calls “Sugababe,” in an ode to an English pop group that swapped all its original members for new ones.

Strebe partnered with biologists from MIT (including famed cloning researcher George Church) to gather cells from a postage stamp the artist had licked, as well as from a living van Gogh descendant—his great, great, great, great nephew—and translate the material into a fully fleshed-out model. The traveling ear currently sits, suspended in gel, in the Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Gallery in New York.

“One day, I realized painting was washed up,” says Strebe, who has a traditional artistic background. “I very much liked the intersection of art and science, the idea of CRISP-R technology, and using the most up-to-date genetic tools creatively.”

Strebe’s work is so technically advanced that the reconstructed ear is not only a precise physical replica; it can actually “hear” gallery visitors whisper into it, using a computer program that mimics the human auditory nerve.

So, is anyone listening on the other side, or are gawking passersby just talking into a void?

Strebe answers with a few questions of her own. “The ear is missing Vincent, so could anyone ever really be listening?” she says. “Would a ship be the same if you reassembled it, years later, with the same parts? How close can we ever really come to the original?”

If this paradox sounds like an echo of the debate surrounding modern cloning, Strebe has reached her goal. She challenges art patrons to expand their ideas of genetic engineering, thinking about how science can be used on an artistic and conceptual level.

“To everyone who finds this creepy: Is a bleeding heart in a Jesus painting not creepy?” Strebe asks. “We don’t live in Disneyland. We live in a time when these questions are important to ask.”