A Stomach Acid-Powered Pill Could Monitor Your Vitals, Deliver Drugs, and More

Photo provided by MIT and Brigham and Women’s

Who needs batteries when you’ve got stomach acid?

Researchers from MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital designed a high-tech pill that runs on the acidic fluids in your stomach, creating enough power to run small sensors inside the body and deliver drugs for long periods of time. The tiny device could have a huge impact on the way doctors treat patients.

A study that tested the device’s effects on pigs was published Monday in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Similar devices are usually powered by small batteries, which can pose a possible safety risk and eventually run out of power. Using the stomach’s natural environment taps into a power source that is safer and cheaper.

“We need to come up with ways to power these ingestible systems for a long time,” senior author Giovanni Traverso said in a statement. “We see the GI tract as providing a really unique opportunity to house new systems for drug delivery and sensing, and fundamental to these systems is how they are powered.”

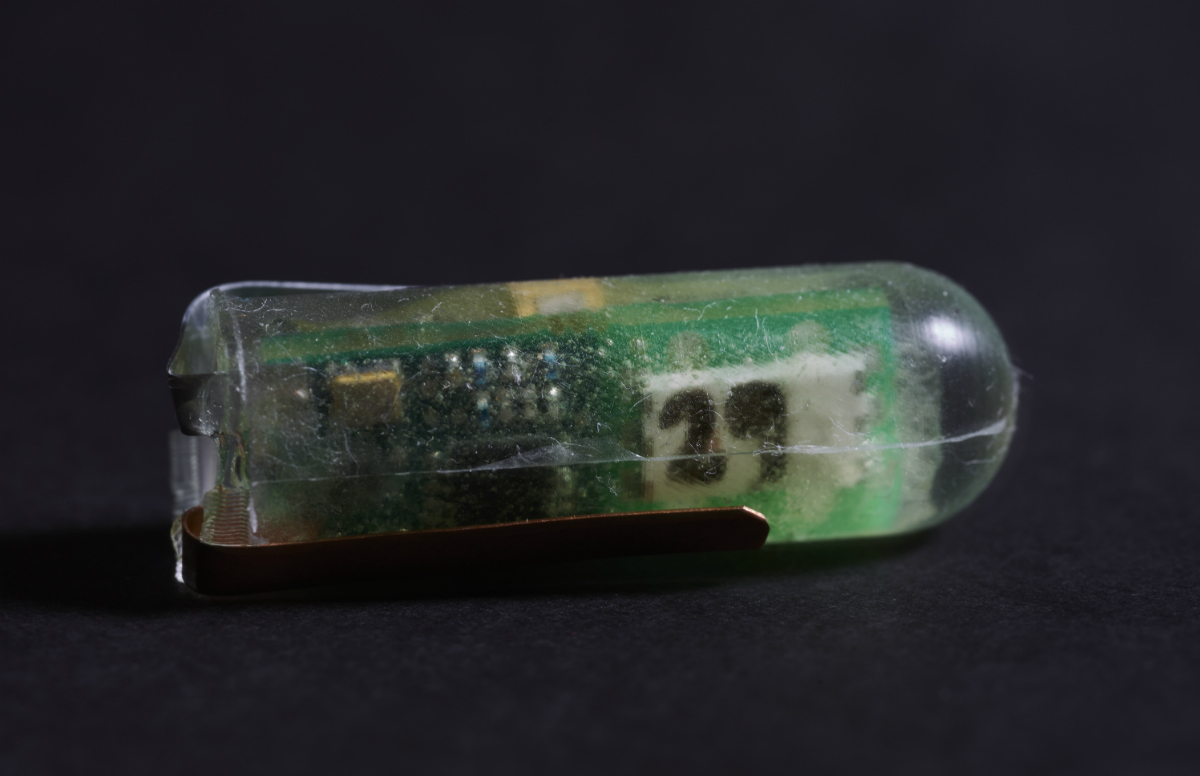

The pill is small—about 40 millimeters long and 12 millimeters in diameter—though researchers hope to shrink it to a third of that size in the next prototype, as well as add other types of sensors and tweak it for long-term monitoring of vital signs.

“You could have a self-powered pill that would monitor your vital signs from inside for a couple of weeks, and you don’t even have to think about it,” lead author Phillip Nadeau said in the statement. “It just sits there making measurements and transmitting them to your phone.”

The idea for the device started with a lemon. When two electrodes, often one copper and one zinc, are stuck into a lemon, a chemical reaction creates electricity, and the lemon’s citric acid carries the current between the two electrodes.

In this device, zinc and copper electrodes are attached to the surface. Just as the electrodes react and create a current in a lemon, zinc reacts with stomach acid to create electricity. In the study, the current was powerful enough to run a temperature sensor and a transmitter that tracks that information, and to release drugs encapsulated by a gold film.

During the study, the device generated enough power to allow the transmitter to send a signal every 12 seconds to a base station two meters away. Once the device moved to the less acidic small intestine—it took an average of six days to travel the digestive tract—the amount of power fell to only 1/100 of what it produced in the stomach, though researchers hope to find a way to harness the power there as well.

“This work could lead to a new generation of electronic ingestible pills,” senior author Robert Langer said in the statement, “that could someday enable novel ways of monitoring patient health and/or treating disease.”