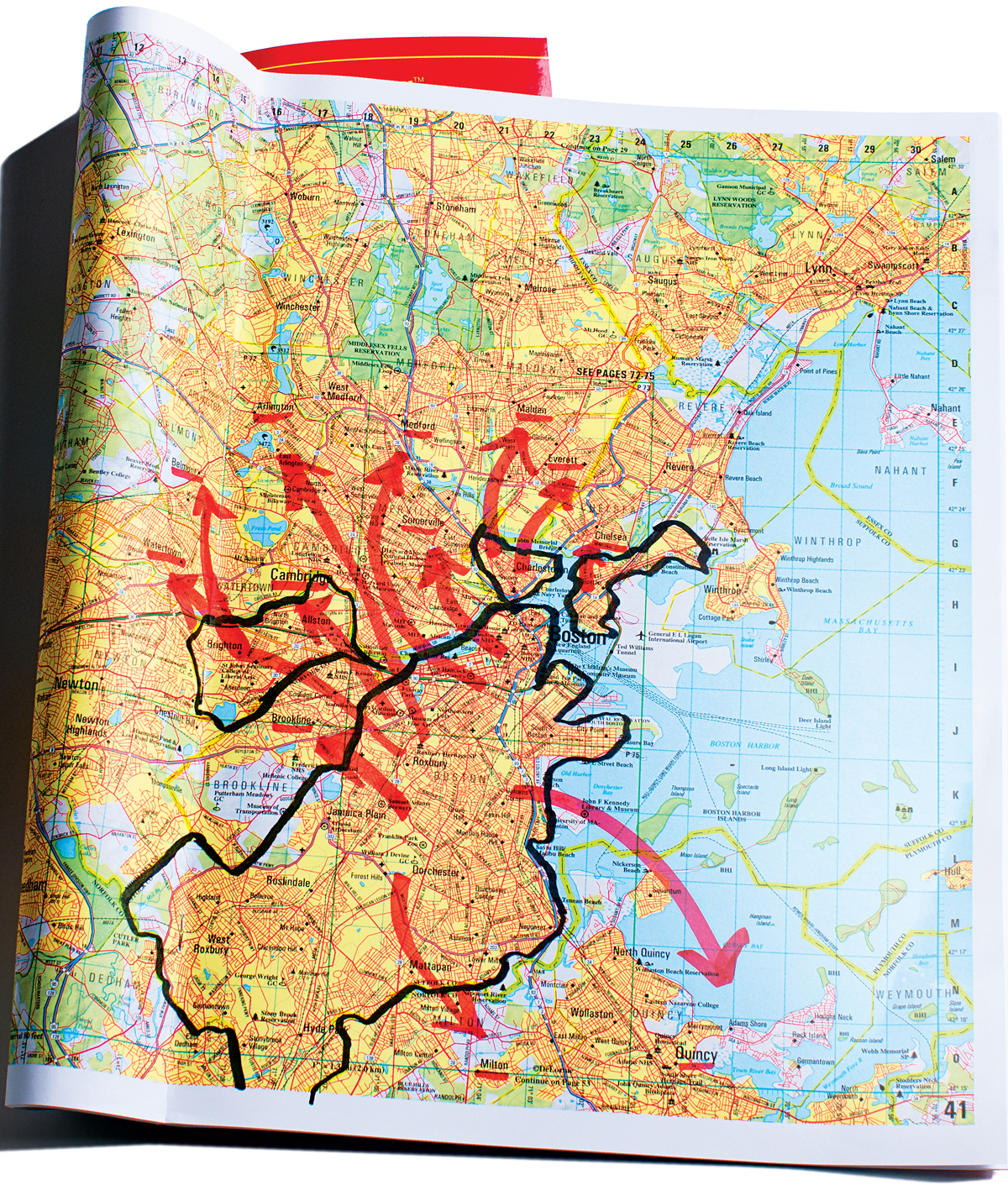

Annex Brookline!

Photograph by Scott M. Lacey

Newly ascended sultans of the Ottoman empire traditionally celebrated their good fortune by murdering all of their brothers. In later years they settled for imprisoning them in the imperial harem where—like the people who dared challenge Tom Menino over the past two decades—they descended into irrelevance and insanity. This practice was simple common sense, actually, because whether you’ve just been elected president of the United States, mayor of Boston, or even just the grand poobah of your local Elks lodge, your first concern must be to consolidate your authority, preferably with a demonstration of raw power that puts the fear of God—or, better yet, the fear of you—into any potential usurpers.

It’s a lesson Marty Walsh and John Connolly would do well to study, because after 20 years of Menino, whose reign was routinely described as imperial, the stakes for his successor will be as high as the towers rising around the city. Come November 5, that successor will be known, and whether it’s Walsh or Connolly, the entire city will be watching closely to see if Boston’s vast machine—the BRA, the police and fire departments, the public schools, everybody right down to the clerks in the parking-ticket windows in the bowels of City Hall—falls in line to carry out their new leader’s bidding, or, left rudderless and skeptical, collapses into a grotesque circus of chaos and corruption. In other words, this is no time for the sort of small, gradual, and pragmatic thinking both men campaigned on.

No, what the next mayor needs is not simply a bigger vision but a bigger city—epically bigger. And that means we’re coming for you, Brookline—and while we’re at it, for everyone else in the 617 area code, too.

In this time of transition, Boston needs to expand, and Mayor Connolly or Walsh won’t have the lay-up Tom Menino had when he campaigned to convert a bunch of downtown parking lots with harbor views into luxury condos and offices for the one percent. The kind of stratospheric growth we’ve seen in the Seaport won’t be sustainable forever. Then again, maybe it doesn’t have to be: Truth is, the idea that all of Boston’s growth ought to occur within our own borders, rather than through regional conquest—er, annexation—is a fairly recent one.

Cities grow to greatness for many reasons. While Boston eventually dominated the economic, political, and intellectual life of the U.S. through much of the 19th century, in 1800 the city was a dollop of marshy land between Mass. Ave. and the North End, home to barely 25,000 people. It was landfill, of course, that over the next century expanded the downtown waterfront and gave us most of the Back Bay, South End, and Fenway neighborhoods. But if we’d limited our expansion to just those parameters, Boston today would cover merely 9 percent of its current land area and, with a population of 120,000, would rank as the ninth-largest city in New England, just behind those jewels of the Nutmeg State, Stamford and Hartford.

Our great expansion didn’t begin until around the same time as the rest of the country’s, with most of Southie joining the city in 1804, just one year after Thomas Jefferson closed the greatest fire sale in history, otherwise known as the Louisiana Purchase. East Boston was added in 1836 (inaugurating a long tradition of everyone else in town asking, “Where is that?!”), followed by Roxbury and Dorchester shortly after the Civil War ended. The watershed year, though, was 1873, when the municipalities of Charlestown, West Roxbury (which also included J.P. and Roslindale), and present-day Allston-Brighton all wisely voted to submit themselves to Boston’s dominion.

And yet the most important vote of 1873 may not have been the “ayes” of all those that joined, but the “nay” of the one town that didn’t. Founded in 1705, Brookline had by the late 19th century grown into its present status as a walled garden where Boston’s wealthy and powerful could fluff their pillows safe from the predations of the city’s teeming horde of Hibernian hooligans. Flush with cash and self-regard, Brookline’s Brahmins turned up their noses at Boston’s embrace by a vote of 707 to 299. (Bostonians, on the other hand, favored the annexation 6,291 to 1,484.) In his 1985 book Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, the Columbia University historian Kenneth Jackson calls this vote “the first really significant defeat” for the urban consolidation movement nationwide.

Brookline’s demurral didn’t put a stop to talk of further expansion, but it essentially turned the tide against Boston’s imperial ambitions. An 1892 story in the New York Times reported on a proposal to absorb Cambridge, which, like many other second-rate towns of its day, found itself struggling to pay for modern roads and sewer systems. The Times story noted that “the overburdened taxpayers are strongly in favor,” but that “principal opposition comes from Cambridge City officers and would-be officers, who dread the passing of their glory.”

The grandest plan of all, though, came from the Brookline lawyer Daniel Kiley, who submitted a bill to the General Court in 1912 that would have combined every city and town within 10 miles of the State House into a 327-square-mile Überboston larger in area than New York City or Chicago—a footprint that today holds nearly 2 million people. Alas, Kiley’s bill fared little better than the Titanic, which sailed a few months later, and the annexation of Hyde Park on New Year’s Day would be Boston’s last. Opportunity briefly flashed again in 1991 when Chelsea went bust, fell into state receivership, and Boston Mayor Ray Flynn extended the offer of annexation, but the city’s leaders managed to wheel and deal their way through the crisis without selling the farm.