Confessions of a Jury Foreman

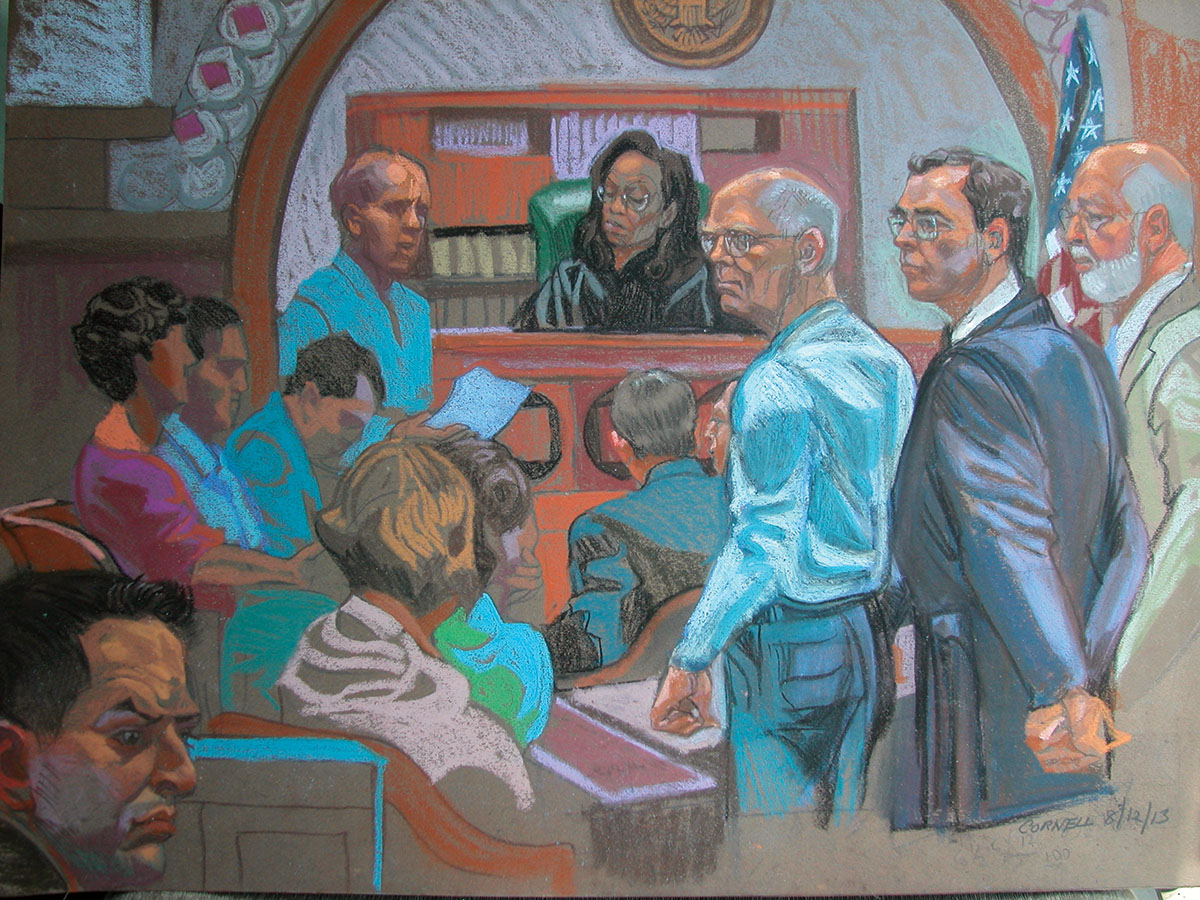

Illustration by Christine Cornell

The Whitey Bulger trial was a turning point in my life. I had been laid off by an insurance company in 2011 and became a stay-at-home dad to my five-year-old son. By the summer of 2013, I was gaining weight and depressed. My wife tried to help, but I had lost my way. Serving as the jury foreman made me feel that there’s no problem that I can’t solve under pressure. It gave me confidence in myself. I’ve always had this feeling that I’m destined, not for greatness, but that there is something out there waiting. I don’t know if this was it. I still think about the trial every day. It’s become a part of me. Yet I hated being the person that I had to be at many times during the deliberations. The pressure was mounting and I was seriously concerned that we were not going to render guilty verdicts on murders that were, in my eyes, beyond a reasonable doubt. When you are involved in the most intense negotiations you could ever be presented with, you do some things that you need to do to get the result you need. This often involves influencing people in many different ways. Some good, some not so good. I did some not-so-good things that still bother me today.

The note to federal court Judge Denise Casper was handwritten in nearly perfect block letters across a greenish steno pad: “Due to multiple personal verbal attacks against a female juror, that have nothing to do with the facts or evidence in the case, I would like to have a male juror excused from the jury.”

It was 11 a.m. on August 6, 2013, our first full day of jury deliberations in the U.S. government’s case against James “Whitey” Bulger. To the outside world, everything was running smoothly. For three months, gangsters and killers, all of whom cut deals with the feds to hang their former boss, sat on the witness stand inside Courtroom 11 at the Joe Moakley federal courthouse and offered their confessions. The stories had a deadening repetition: Bulger killed a person, someone else buried the body, and Bulger took a nap. After showing us guns, bones, and the inside of blood-splattered cars, the prosecution had done its job. The defense had rested, without putting Bulger on the stand. Five stories below the jury room, dozens of TV trucks and reporters dappled Northern Avenue near the courthouse steps, waiting, with the rest of the world, for us to send Bulger away for life. No one could have guessed that down the hall from Judge Casper’s chambers and past the jury-room door, the wheels of justice were spinning right off a cliff.

Juror No. 12, a middle-aged author of historical Revolutionary War books with short, curly hair, confided in us that her son had died due to medical malpractice. She sued and lost. It was a sensitive subject. Already, however, a man from Framingham, often identified in the media as Juror No. 5, had brought it up at least three times. He believed that No. 12 was anti-government and bitter with the justice system due to her bad experience in court, and was looking for ways to stonewall the prosecution by delivering as many not-guilty verdicts as possible. He may have been right, and part of me thinks he was, but you don’t keep bringing up a mother’s dead child. We told him his comments were inappropriate, but he kept pushing.

We were discussing a piece of evidence when No. 5 blurted out, “Her son died, so that’s why she feels that way.” No. 12 instantly shot up from her seat and left the room. Disgusted, I stood and shouted, “That’s it!” before chasing after her.

I found No. 12 inside an empty office. With the doors closed, I could hear jurors down the hall screaming at No. 5, “What the fuck is wrong with you? We told you three fucking times not to bring up the kid. It doesn’t matter!” Several other jurors soon joined us, and I told No. 12 that I wanted No. 5 off the jury. We all agreed, so I dictated the handwritten note and sent it to the judge.

In an era when “civic duty” is an anachronism and less than 50 percent of Bostonians bother to vote for mayor, here were 12 jurors and six alternates sacrificing three months of our lives for this trial. Many people gave up vacations, graduations, weddings, and funerals. My favorite uncle died and I was unable to attend the service. But this was nothing compared with the jurors who had to work on weekends to make ends meet because they had exhausted their benefits at work, all so they could fulfill their duty. Suddenly, everyone’s efforts were at risk and we feared the possibility of a mistrial if we kicked No. 5 off the jury. And in truth, this blowup wasn’t the only time during five days of secret deliberations that jury members—myself included—nearly blundered Boston’s trial of the century.

Juror No. 12 was still furious at No. 5 when she walked back into the jury room a half-hour later. We took our lunch break and had to keep them separated while we waited to hear back from Judge Casper. In low voices, I spoke to several jurors about how we needed to keep No. 5 under control. He seemed like a 14-year-old boy trapped in the body of a man in his forties. I determined we could not jeopardize everything we had done as a jury, and I would not let one person bring us down. Before starting deliberations, I pulled No. 5 aside. “A note was written to the judge,” I told him. “However, no name was on the note, so you still have a chance to be part of this jury. Are you with us?” He agreed to behave. So when Judge Casper asked us whether we’d been able to resolve our issues, the answer was an honest “yes.”

As deliberations continued, I got to learn more about what made people tick and what was important to them. It seemed to me that what No. 5 most wanted was to get his hands on the guns used by Whitey and his gang. The first day of deliberations, his eyes lit up when he asked, “Can we really see the guns if we want?” It became apparent that if I let No. 5 see the guns, or even better, handle the guns, then I would gain leverage over him to influence him when I needed it. When he said that he wanted to see if one of the guns had a scratched-out serial number—as the gun involved one of the charges against Bulger—I finally relented in hopes of keeping him under control. After examining the firearm in the jury room, he was the happiest fortysomething man I have ever seen. Personally, I could have cared less about seeing the guns. We saw them several times in court, and that was enough for me.

Jury deliberations are all about the science of human nature. They are about finding consensus, the quest for truth, and making a just decision. But with 12 random strangers confined together like a submarine crew in a guarded room, where every memory, experience, and preconceived notion not only bubbles to the surface but is also scrutinized by 11 of your peers, juries are also about power, control, and, eventually, forgiveness. At least that was my experience as Juror No. 11.

Bulger’s trial was historic in many respects. Not only was he Boston’s most notorious mobster, but the trial was remarkably complex: There were 32 criminal counts, and within one of those counts there were 33 racketeering acts, several of which even had multiple parts. That meant that the jury had to deliver “guilty” or “not guilty,” or “proven” or “not proven” verdicts 70 separate times. Nineteen of the racketeering acts involved murder. And even though I knew the pressure to deliver the right verdict on each and every count would be crushing, I wanted to be on the case from the first day of jury selection when we learned it was the Bulger trial. After two years of unemployment, I had finally landed a job at a bank and was supposed to start the same week as the trial. I couldn’t tell my wife it was Bulger’s, but she knew the case could last months and was worried that I might lose my first job offer in a long time. I didn’t care. I thought to myself, This is the biggest deal ever. This could be the greatest thing I’ve ever done.

During the testimony phase of the trial, jurors were forbidden from talking to one another about the case. We were a collection of eight men and four women, ranging from 24 to 65 years old. There were no lawyers or doctors, though there was a small business owner and a nurse. It was a room packed with hard-working, ordinary people. By contrast, the jury room was filled with posh leather chairs, a shiny rectangular table, a kitchenette stocked with cereal and snacks, and a pair of restrooms. To kill time, we’d stare through the large windows at the outside world. Sometimes, we would try to guess who was testifying that day—was it Stephen Flemmi? Kevin Weeks?—by counting the number of media trucks parked on the street below. Once, during a rainstorm, we noticed that defense attorney Jay Carney had left the windows to his BMW down. We sent a note to the court clerk and found ourselves laughing a few moments later when we saw Carney rush outside to his car.

As notorious as Bulger is, at 83, he wasn’t much to look at. He did the same thing every day, scribbling or pretending to scribble on the yellow notepad in front of him. Occasionally, he’d whisper into his lawyer’s ear. A fellow juror told me Bulger once tried to stare him down, but personally, I never paid Bulger much attention. Watching killers and mobsters testify was far more interesting. It was better than the movies. I mean, these were the real guys. They’d be on the stand a few feet from their old boss, whom they hadn’t seen in 30 years, and say, “Hey, Jimmy,” or “Hey, Jim,” the same way you’d greet an old pal. But Bulger only responded once. I’ll never forget watching Weeks testify that Bulger was a “rat,” and then hearing Bulger scream, “You suck!” followed by a rat-a-tat of “fuck you”s. But other than that, the most exciting thing Bulger ever did was ask for a bathroom break, which the jury loved, as it gave us a chance to stretch our legs. Once the prosecutors and defense attorneys rested and turned the case over to us, however, there was no shortage of action.

Our first order of business was to elect a foreman. I had been sizing up the other jurors during the entire three-month trial. I wanted to be foreman from day one, and I needed to know where I stood. I knew I could do the job. I knew what needed to be done. I knew I could get it right. When the time came, I raised my hand for consideration—but so did No. 5, as well as another juror who later told me she did so to make sure No. 5 did not get the job. I won, 11 to 1.

This was a heavy responsibility, and I took it very seriously. The following day, however, I lost my cool. One of the jurors wanted to ask Judge Casper if we had to be unanimous in our decisions on “proven/not proven” verdicts for the racketeering acts, which included all of the murder charges, the same as we did for “guilty/not guilty” verdicts on the overall criminal counts. Without knowing the answer, I immediately told her “no,” and moved on to something else. The woman did not say a word, but I watched her stand up from the jury table and walk out of the room. Forced to take a break, I had time to reconsider the juror’s question and realized that I didn’t know the answer. I felt bad for dismissing her, and when the woman returned 10 minutes later, I could see she’d been crying. I apologized and gave her a hug. I then forwarded her question to the judge. Turned out she had been right all along, and I promised the jury I’d be more open-minded.

From the first day of deliberations, I was incredibly stressed thinking that we wouldn’t get a guilty verdict. Inside the jury room, with the air conditioning pumping, we attempted each charge in the order it appeared on the indictment, but that meant dealing with the murders first. I quickly realized we were not ready for such a daunting task. Instead, we talked through the money laundering and extortion counts, for which there was an overwhelming paper trail of evidence. These guilty verdicts came fast and easy and I was pleased with how we, as a jury, were moving along. On day two, we dove into the so-called Notarangeli murders, by far the most contentious and complicated deliberations of the trial.

The Notarangeli murders were a series of assassinations carried out in 1973 and 1974 by Bulger hit man John Martorano, a.k.a. “The Executioner” or “The Basin Street Butcher.” North End Mafia boss Jerry Angiulo allegedly recruited Bulger to execute Alfred “Indian Al” Notarangeli, leader of a rival Somerville-based gang, because Angiulo suspected Notarangeli of killing one of his bookmakers.

Perched on the witness chair, just a few feet from me and the jury, Martorano wore a navy-blue suit with a light-blue shirt and a matching pocket square. He testified that he and Bulger made several attempts to snuff out Notarangeli, mistakenly killing Al Plummer and Michael Milano along the way. Plummer, a member of Notarangeli’s gang, was shot driving a car that Martorano believed was carrying Notarangeli. Milano, an innocent bartender, was shot in a case of mistaken identity because he drove a car that looked like Notarangeli’s brown Mercedes. In each case, Martorano testified to acting at Bulger’s behest or alongside Bulger himself. Martorano admitted that he also killed Notarangeli gang member William O’Brien before finally slaying Notarangeli in a 1974 drive-by shooting. Bulger, Martorano said, served as backup and followed behind in a separate car.

Initially, it was hard for me to think that Bulger was not involved. If Martorano said Bulger was there in the “crash car” or “boiler,” then I believed him. Why shouldn’t I? Martorano had already admitted to murdering all these people. Why would he lie about Bulger now? I flashed back to a speech I’d given to the jury before we’d begun deliberations about our responsibility as jurors and how at some point we would have to believe the “bad guys.” I wanted them to understand that we would have to take the word of wiseguys and killers to do our job. And now, with Martorano’s testimony on the Notarangeli murders, we were faced with exactly that.

I knew Bulger was going down. Everybody did, so I was shocked at the amount of reasonable doubt in the room over these killings. Once again, Juror No. 12 made her presence known. She had grown increasingly disgusted with the federal government as the trial went on, and felt uneasy about the cozy relationship between the FBI and the cooperating witnesses, particularly Martorano. There was no doubt that he got the plea deal of the century. Martorano admitted to 20 murders and did only 12 years in prison—he was forgiven altogether for killings in Oklahoma and Florida, both of which carried the death penalty—so whatever he told the feds must have been pretty damn good. Sitting at the jury table, No. 12 repeatedly asked the same questions: Other than Martorano, who placed Bulger at the crime scenes? How many witnesses were there? Where was the physical evidence? The answers were hard to find and she was persistent, challenging us to think clearly about the testimony.

I was resistant at first and was one of the hardest to sway. I simply chose to believe Martorano. But No. 12 could not be ignored as more jurors joined her side and leaned toward a not-guilty verdict due to the lack of corroborating evidence. At one point, a juror who was voting not guilty walked up to me and said he thought several jurors, including me, were pro-guilty on every charge no matter what. I told him he was wrong about me, but from that point on I was mindful of how everyone perceived me. It was an effective way to call me out and pressure me to vote not guilty. As if by design, I suddenly had one of those “Wow…you’re right!” moments. I realized that I couldn’t believe everything I heard and that I did need to be more open-minded. No. 12 was correct. Since there was no physical evidence or corroborating witness in any of the Notarangeli murders, it all boiled down to whether we believed Martorano. Given Martorano’s platinum deal with the government, it didn’t take a genius to think that maybe, just maybe, Martorano wasn’t telling the truth the whole time. I ultimately changed my mind and voted not guilty—one of eight gut-wrenching times I would do so.

Looking back, it haunts me thinking about the victims and their families who never received justice. I see their names and faces swirling in my head. Martorano admitted to killing innocent men, but the government’s plea deal enabled him to elude a lengthy prison term and any real accountability. When we voted not guilty on Bulger, we effectively slammed the door on the last chance victims’ families had for justice. In my perfect world, there would’ve been more evidence and we would have delivered a guilty verdict, but we just did not believe Martorano. It was a hard lesson for me to learn, and as the deliberations continued, my frustrations deepened.

The pressure to get all 70 verdicts right in such a notorious trial was tough, but at times the loneliness made the job seem like a punishment.

Each day, we deliberated from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., and the mood was all business. We took short breaks as needed and at the end of the day, Judge Casper warned us not to speak with anyone about the case or listen to the media coverage. That meant I couldn’t tell my family or my friends down at the tavern that I had been elected foreman of the Whitey Bulger trial. It wasn’t easy. I found myself walking out of rooms, functions, and restaurants all the time because I couldn’t watch the news or listen to people talk about it. Unable to confide in anyone—including other jurors—I shut down. I isolated myself and was always off thinking in another room, absorbed in the trail of murder victims that Whitey left in his wake. Of course, friends became suspicious that I was a juror on the trial, but I never told a soul, not even my wife.

The closest I came to blowing my cover came six weeks into the trial on July 16, 2013, when a jogger in Lincoln discovered Stephen “Stippo” Rakes lying dead in the woods. Rakes was an extortion victim of Bulger’s who owned a liquor store in South Boston and despised the kingpin. He was a potential witness and everyone, including the jury, assumed he’d been killed to keep him from testifying. I was stunned, and it terrified several of the jurors. We were not sure whether we were allowed to talk about it, but people were whispering to one another that they feared for their lives. Two jurors told me that they’d begun sleeping with a gun. Later that night, I came home to a frightened wife. I’d been on jury duty more than a month, so when the news of Rakes’s death aired, she pleaded with me to tell her if I was in danger and serving on the trial. I never gave in. Two months later, we learned that it seemed to have had nothing to do with Bulger when a 69-year-old man named William Camuti, who owed Rakes money, was charged with slipping cyanide into Rakes’s coffee and dumping the body.

To cope with the loneliness and mounting pressure, it was important for me to go to a different place either physically or mentally. I would escape to my sister’s campground near Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire, and find solace by walking through the pine trees or reading a Dan Brown book. I did a lot of soul-searching in the mountains, but I could never drown out the trial. And I admit: I began to crack a little.

By the fourth day of deliberations, we had agreed on verdicts for most of the charges and had finally made our way through the Notarangeli murders. The end was in sight. But something inside of me was still boiling, leftover frustration from my earlier disagreements with No. 12 about whether to believe Martorano.

We were deliberating over the murder of gangster Tommy King, a rival of Bulger’s. Martorano told the jury that he had shot King in the back of the skull inside a parked car, and that Bulger had driven off with the body. But unlike the Notarangeli murders, Martorano wasn’t the only witness. We had heard the same story from several people who were in on the hit.

While arguing for a guilty verdict, Juror No. 12 suggested that this time around we believe Martorano. I couldn’t believe my ears or keep my mouth shut. “But we’re not going to believe something John Martorano said, are we?” I said sarcastically, referring to her refusal to believe him during the Notarangeli murders. No. 12 went through the roof. She slammed her pen down, stood up, and said, “I want off this jury now! I feel like no one has been listening to me. I want you to write a note to the judge and tell her that I want off this jury immediately.” She stormed out of the room.

Scanning the other 10 faces left at the jury table, I could see that everyone was mad at me. Someone told me to apologize to No. 12. I said, “I know,” and walked toward the door. I had mocked her and been a smart-ass, but I was upset because suddenly she wanted to believe Martorano and she had made such a big deal convincing everyone to vote not guilty on several earlier murders based on not believing him. I knew there was corroborating evidence this time in the King case, but I had to be a dick. I had to do it. I just didn’t want her to fucking railroad this thing. And now I’d sent us all on a collision course with a possible mistrial if she dropped out of the jury.

I collected my thoughts as I followed No. 12 across the hall and into an empty judge’s chambers. I knew this was going to be one of the most difficult conversations of my life under the most extreme pressure imaginable. But I understood what I had to say. Personally, I had too much time invested in this trial to let it all slip away because of something I said in the heat of deliberations.

No. 12 was pacing near the window when I entered the room. She was crying and visibly angry. “I’m sorry,” I said. “You deserve more respect than that.” No response as she continued to pace. I had to get her back in that jury room. I knew that if she was adamant and wanted off the jury, then the whole proceeding could be over and declared a mistrial…all because of me. With that in mind, I said what I had to in order to get the result I wanted. “I need you in there,” I said. “You are a true patriot and this country needs you. You carried the day in the Notarangeli murders. Do not give up on the government now. I need you in that room. Let’s finish this so we can go back to our lives.”

Moments later, we walked together into the jury room, where we delivered a guilty verdict on King. After I apologized to No. 12, we hugged. She was able to see the good in me and realize that I was acting out under the pressure to deliver what I thought were the right verdicts. She saw that I was just being an imperfect human. And she forgave me.