Fare and Square

Illustration by C.J. Burton

As riders, our war with Boston-area cab drivers is fraught with grievances. For years, we have bolted on fares, acted boorishly, and vomited in the back seat. (Oh, we have definitely vomited in the back seat.) For their part, cabbies have stretched fares, not known how to get places, and chafed at having to accept credit cards. This last offense has been the biggest flash point lately. Because the credit card readers in taxis charge drivers a 5 or 6 percent processing fee—much higher than the rate paid by retail stores—cabbies feel like they’re getting robbed when we use plastic. Tales of drivers with “broken” readers—broken until riders profess they have no cash, that is—are common.

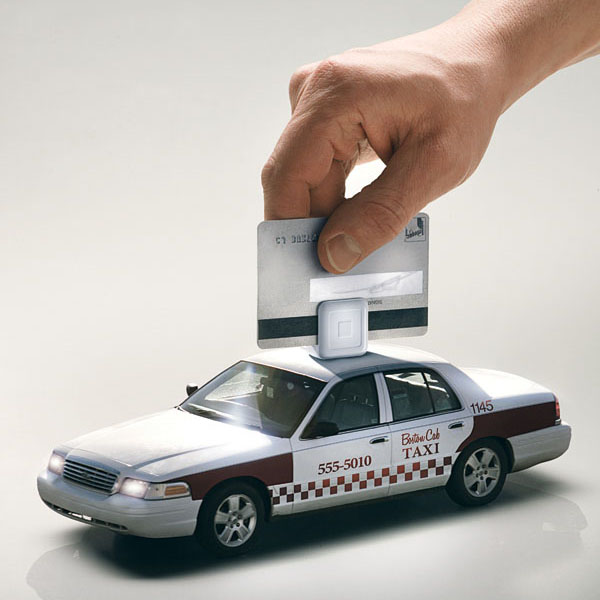

So I reacted with great trepidation one recent night when, at the end of a ride from Cambridge to Brookline, a friend pulled out her Visa. To my surprise, the driver took it and, lo, didn’t utter a complaint. He swiped the card through a square white attachment on his smartphone and handed the thing back without so much as a frown. “Do you get a better rate with that?” I asked. Provided by a company called Square, the device, along with its corresponding app, allows smartphones to run credit cards. “Yeah,” the driver said, “3 percent.”

Actually, Square charges just a 2.75 percent processing fee. It also guarantees deposits by the next day—a big deal for drivers who are used to getting cash immediately. The device has become increasingly popular among local cabbies, who typically pay all their fees up front and then keep every dollar in fares they make. In other words, the processing fees directly reduce what goes into their pockets. “We are seeing it pop up in more and more vehicles,” says Corey Pilz, of the Cambridge License Commission, which regulates taxis for the city. Square and other mobile-payment apps, such as Uber and Hailo—both of which let riders hail and pay for cabs with smartphone apps—may not solve every conflict between riders and drivers, but “it’s definitely a bridge,” Pilz says.

Of course, there’s a catch. And it’s a big one. It is illegal for cab drivers in the city of Boston to use Square. Cabbies are required to be members of a radio company—a group that provides communication for drivers and directs them to riders—and those associations have all contracted exclusively with one of two mobile-payment companies, Verifone and Creative Mobile Technologies. Those are the companies that set the high rates and profit from them.

That hasn’t stopped all Boston drivers—who are required by law to accept credit cards—from trying to pay less in fees. “I do know for a fact some of them are [using Square],” says Steve Sullivan, the general manager of Metro Cab, one of the five big radio companies in Boston. Sullivan says he believes that the number of Boston drivers using the app is relatively small, and that most of the ones who do are just keeping it as a backup, in case their normal credit card readers go out. But since the evidence is purely anecdotal, and it would be difficult for authorities to tell if a driver were using Square, it’s hard to know how prevalent use of the app is in the city.

You’ve got to wonder, though: If something like Square can bring peace between cabbies and riders, why not make it legal? Plenty of businesses across the city, including food trucks, already use it. “We would consider allowing anything,” says Mark Cohen, the director of Boston Police’s Hackney Carriage Unit, which oversees the city’s cabs. “The door is always open for new technology.” He says that if somebody were to present Square to his division, they would consider permitting it.

But for the app to move forward, it would have to crawl through the requisite tangle of city regulations and private interests, including those of the radio associations and current mobile-payment companies. And that doesn’t seem to be happening. “Hackney has just ignored it until now,” says Donna Blythe-Shaw, the head of the Boston Taxi Driver Association. “I don’t have much faith in Hackney, quite frankly.” And so, for now at least, the war goes on.