Training Our Kids for the Next School Shooter

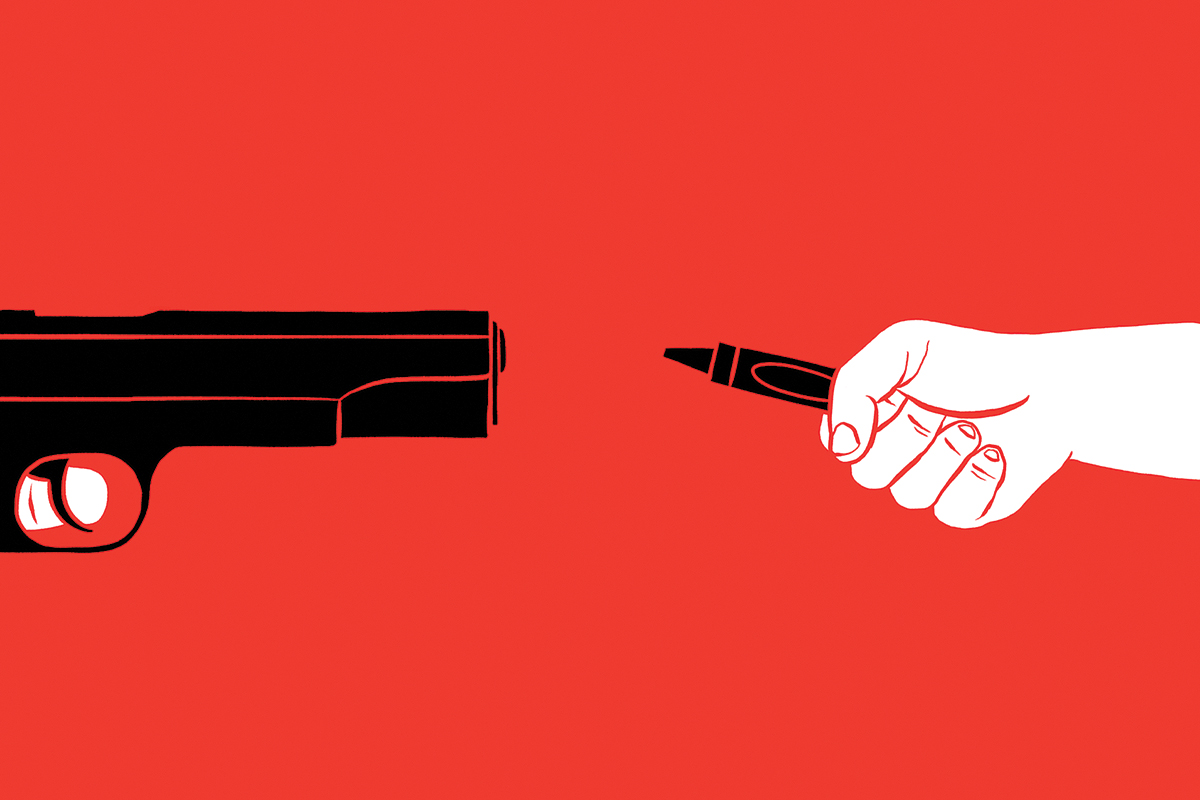

Illustration by Matt Chase

My friend’s eight-year-old daughter came home from school recently and bolted into the bathroom. When she came out, her mother asked, “Is everything okay?”

They’d had a safety drill at school that day, her daughter explained, at which they’d been told, among other things, that if an intruder entered the school while they were in the bathroom, they should lock the stall and climb onto the toilet seat so he couldn’t see their feet. “I’m never going to use the bathroom at school again,” she announced.

My friend quickly reassured her daughter that the odds of something like that happening were slim. But as she recounted the story to me later, she added, “In the back of my mind, I’m thinking, I don’t want you to use the bathroom either!”

With 52 school shootings last year as of October, gunmen have become the proverbial atomic bomb of my kids’ generation—a thing that could happen, a thing we need to prepare for. Over the past year or so, in nearly every district in Massachusetts, schools have aggressively ramped up their training for active-shooter situations. The first thing they need to communicate to our kids is that there’s a possibility, however slight, that a killer might be coming for them.

How kids are taught is up to each school district—the state lacks a standard protocol. I first heard of the approach in my town, Wayland, at my kids’ elementary school last spring. Lured by the promise of free childcare and pizza, I attended a meeting billed as an overview of new safety procedures. I had no idea what I was walking into.

Think for a moment about the unthinkable: What if your child’s school was infiltrated by a mass murderer? What would you want them to know to make it out alive?

Then think back to when you were a kid. If you grew up in the ’50s, you were probably taught to duck and cover to survive aerial bombings. In the ’80s, we were led single-file down to the “fallout shelter”—the school basement—to dodge a nuclear attack. By the end of the 20th century, the standard response to any threat—be it weather, accidents, bombs, or intruders—was the lockdown: Pull down the curtains, be quiet, and lie still on the ground.

All of these approaches were passive—shelter, hide, stay quiet. But what happens when the intended target is you?

After the tragedy at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, it became clear that the passive approach doesn’t work when a killer targets kids. On that horrific day, 52 teens and four staffers huddled under tables in the library as two students roamed the hallways brandishing shotguns, a carbine, a semiautomatic handgun, and pipe bombs. Just around the corner was an emergency exit leading out to the sidewalk. Yet anytime the kids peeked out, teacher Patti Nielson shrieked in panic, “Under the tables, kids, heads under the tables!” Four minutes later, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold burst into the library and killed 10 teenagers.

The lockdown approach continued to fail at Red Lake, Virginia Tech, and during numerous other active-shooter situations, until the brutal slaying of 20 children and six staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in December 2012 finally led to a change in concept by the government.

Thirteen months after Sandy Hook, Governor Deval Patrick established the Massachusetts Task Force on School Safety and Security, which proposed several ways to enhance a lockdown, including barricading doors, distracting or countering the assailant, and self-evacuation. “No child will be able to succeed academically if they don’t first feel safe in school,” Governor Patrick said when he signed the executive order, “and no teacher will be able to teach at their best if they aren’t confident there’s a plan in place to ensure their school is well prepared for an emergency.”

Last year, the town of Wayland adopted a version of this response strategy called ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate), created by Dallas-area police officer Greg Crane in 2001. Shortly after Columbine, Crane asked his wife, an elementary school principal, how her school handled emergency situations. She told him: “The teachers get everyone in a classroom, lock the door, turn off the lights, sit in the corner, and wait for the police to arrive.” For the first time, Crane understood why so many people were killed and wounded in school shootings: The targets were too damn easy.

So Crane devised a program that instead provided options-based, proactive survival strategies. “It’s a fallacy to believe that a passive response, or relying on a locked door, will always maximize survival chances,” Crane says. ALICE encourages individuals to participate in their own survival—to read the situation and make decisions in the moment. “A one-size-fits-all plan will always be inadequate,” he maintains. Nearly 15 years later, ALICE is now the most widely used active-shooter response program in the United States.