How the Harvard Kennedy School Abandoned America

And just when we need it most.

It was the first day of December on Harvard Kennedy School’s campus, and Kellyanne Conway was wearing a cardigan the color of Donald Trump’s hair. A fitting choice, perhaps, for a campaign manager whose candidate had recently pulled off the most sensational presidential upset in American history. A longtime GOP pollster who now finds herself at the epicenter of power in Washington, Conway was surrounded by nearly a dozen fellow political hotshots who’d led the Trump or Hillary Clinton campaigns. Together they sat in a wood-paneled conference room filled with white-clothed banquet tables. Tidy rows of tabletop mikes and carafes of water conjured an air of erudition and gentility.

Since 1972, HKS’s Institute of Politics has invited key confidants from the Republican and Democratic presidential tickets, from Mary Matalin to David Axelrod, for the purpose of capturing a “first draft of history,” as the school likes to put it. Over the past several decades, the ritual had largely consisted of journalists asking political gurus questions about moments in the campaign that had been covered in the press several times over. Even when campaigns ran hot, dialogue here had remained cool. The losers kowtowed to the victors and everyone complained about Saturday Night Live impersonations. Afterward, participants proceeded to a bar to cordially clink glasses before retiring to their homes for the winter.

Not anymore.

Nearly two hours into the 2016 event, Conway’s deputy praised former Breitbart executive and controversial White House chief strategist Steve Bannon—who’d accepted an invitation to the conference but pulled out at the last minute—as “an unbelievably brilliant strategist.” In response, Clinton’s campaign communications director, Jennifer Palmieri, let loose. “If providing a platform for white supremacists makes me a brilliant tactician, I am glad to have lost,” she fumed, adding, “I would rather lose than win the way you guys did.”

“No, you wouldn’t,” Conway sneered. “No, you wouldn’t.”

Moments later, Conway continued, “Do you think I ran a campaign where white supremacists had a platform? Are you going to look me in the face and tell me that?”

“It did,” Palmieri countered. “Kellyanne, it did.”

“Guys, I can tell you’re angry, but wow,” Conway later retorted. “Hashtag, ‘He’s your president.’ How’s that?”

The spectacle instantly made national headlines, and for good reason: No scene, perhaps, better embodied today’s political landscape, at a time when just about the only thing liberals and conservatives agree on is that government in Washington, DC, is more antagonistic and hopeless than ever. The high-profile yet ultimately chaotic and unproductive meeting of America’s most powerful political minds would also seem to be equally indicative of the state of affairs at Harvard Kennedy School. Here on the shores of the Charles, you’d think that the cradle of public-policy education would offer some optimism in these fractious times. After all, HKS cranks out hundreds of well-meaning graduates each year—exactly the sorts of dreamers many of us assume will free us from the shackles of today’s unprecedented partisan gridlock. But will they?

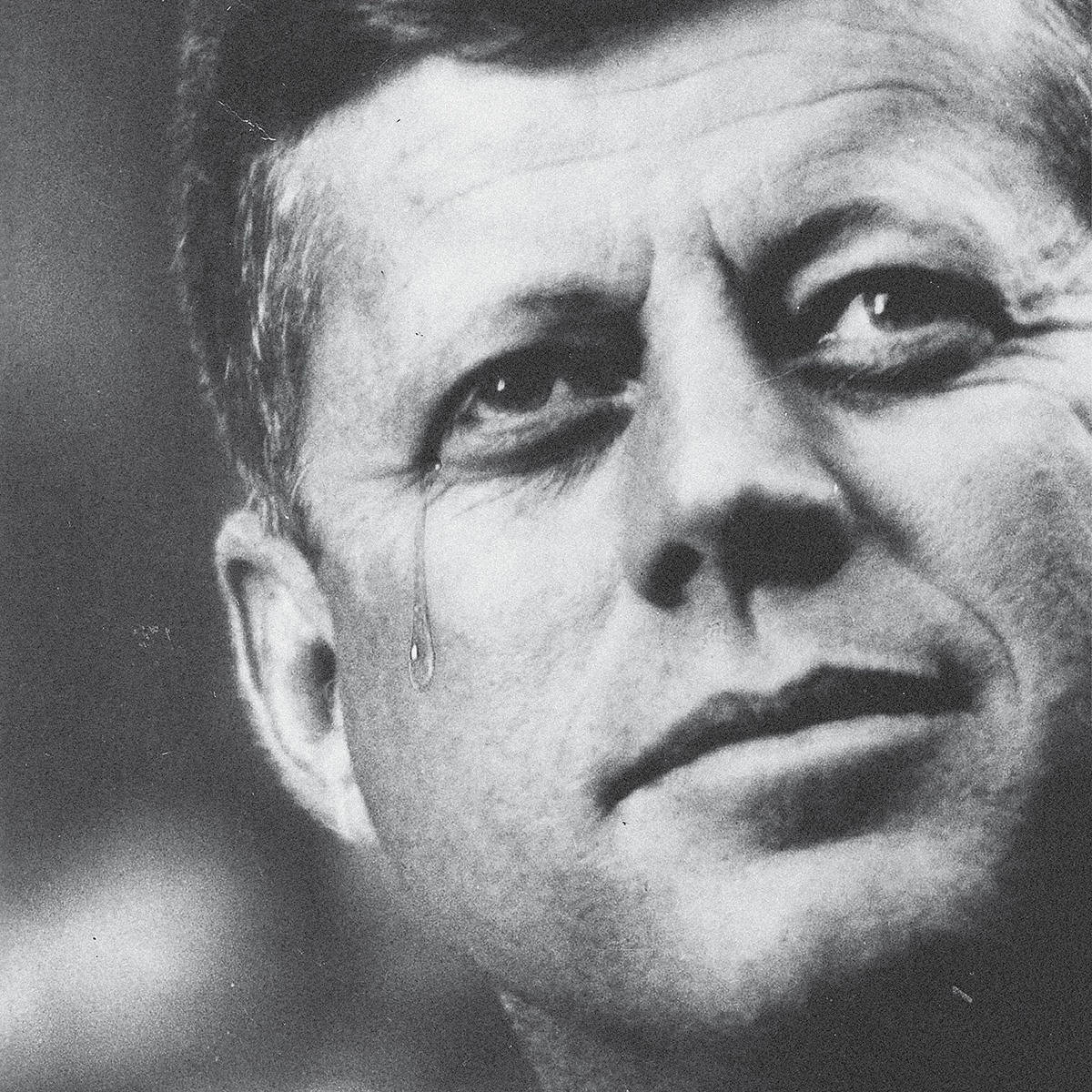

In the 1960s, the graduate school hitched its star to the legacy of John F. Kennedy, with the thought that it would recruit the country’s best and brightest and mold them into America’s next great public leaders. Today, though, all signs point to something far different. The school’s mission, critics say, has strayed from the ideals of its Kennedy namesake, and the curriculum no longer emphasizes government service, also preparing students for any number of far more lucrative careers in the private sector. While the school is cagey about its acceptance rate, it’s believed to be several times higher than those of Harvard’s other schools. What it lacks in exclusivity, HKS seems to make up for in big names, relying heavily on its world-famous alums and powerful VIP speakers to maintain the status quo and convince fresh faces to keep signing up for what has long been considered a less-than-challenging degree.

HKS dean Douglas Elmendorf says the school hasn’t given up on the public sector, but he’s also not losing sleep over HKS grads scratching at the door of the consulting world. “I’m agnostic about what path our students take in advancing public purpose,” he says, adding that he does want “a significant number of them to go work for a government.”

When the Kennedy family bestowed its name on Harvard’s school of government more than 50 years ago, HKS was supposed to inspire and produce the next generation of political lions. But as we venture deeper into this era of hyper-contentious politics in DC, it remains to be seen whether the school is going to play a relevant role and provide much-needed leadership and solutions. After talking to students, graduates, and faculty, though, one thing seems clear: You no longer go to Harvard Kennedy School to grease the wheels of democracy; you go to grease your own career track.

Harvard’s public-policy school was built after Lucius Littauer (center) gifted his alma mater an unprecedented $2 million. / Photograph by Bettmann/Getty Images

From its inception, HKS had been the unwanted stepchild of parent Harvard. In the early 20th century, the very idea of a professional public-service graduate school drew the ire of faculty stalwarts who’d already endured the establishment of the business school. College brass worried that such an enterprise, even more so than Harvard Business School, would dumb down their own scholarship. If not for an unprecedented $2 million donation—the largest from a single donor in the university’s history at that time—from a Harvard alum named Lucius Littauer during the height of the Depression, there may have never been a Harvard Kennedy School.

Littauer, who’d made his fortune as a businessman after inheriting his father’s glove-making empire, had an ax to grind with the government. After serving five terms as a right-wing congressman from New York—and somehow managing to elude serving a jail sentence following a conviction for smuggling a diamond tiara into the country in 1914—Littauer emerged as an outspoken critic of DC, particularly the New Deal. Behind his record-setting gift to Harvard was an anti-government edict that today reads like a precursor to the Tea Party. Citing the “growing invasion of government into every aspect of our nation’s life,” Littauer offered his bequest as “the best hope of avoiding disasters arising from untried experiments in government and administration.”

In 1936, the same year that JFK first stepped onto Harvard Yard as a freshman, the school that would eventually bear his name was officially established. When the Graduate School of Public Administration began, it aspired to enhance the competency of midlevel career bureaucrats in Washington. At first, the program attracted mostly academics, who were taught by professors from a hodgepodge of other Harvard departments—giving the school a ragtag feel. Were professors grooming dutiful bureaucrats or civic-minded scholars? A generation of statesmen or PhDs? Key questions remained unanswered while the school languished for decades, underfunded and unfocused in its direction. Harvard president James Bryant Conant once said that a degree from the school “wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.” In his outgoing 1953 address, with the tone of an ashamed father, he called the school his “greatest disappointment.”

Then came the Kennedys. Less than a month after JFK’s assassination, family members gathered at a Manhattan club and hatched the idea of a memorial to inspire students to embark on careers in public service. It was an easy sell. After all, government at the time was enjoying a star turn. According to Pew Research Center, more than 75 percent of the country trusted the federal government in 1964 (that number was 24 percent in 2014), and the federal workforce was multiplying like never before thanks to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. “In the early days of the Kennedy School,” says Archon Fung, the school’s current academic dean, “we imagined ourselves training people as policy analysts and as very high-level staffers in the federal government in Washington. In that era, a lot of people thought you could solve most public problems from that position.”

A master plan designed by famed architect I. M. Pei (one that never fully materialized) called for a sprawling campus, complete with a museum and presidential library in addition to the school. Having lacked funds since the day its doors opened, the school accepted a $10 million check from the Kennedy family, taking on the Kennedy name and officially spawning the John F. Kennedy School of Government. It didn’t take long, though, for Harvard to rankle Camelot.

The realm of public policy breaks down into two camps: those who rely on leadership and instincts, and those who rely on numbers and science. JFK is best remembered as doing the former, for his daring during the Cuban Missile Crisis and his ability to inspire a nation—a man of feeling more than technique. The school, on the other hand, had always leaned the other way, championing age-old disciplines of economics and empirical analysis. From the start, the school and the Kennedy name had made for odd bedfellows, and the rift was about to widen.