Dying While Black and Brown

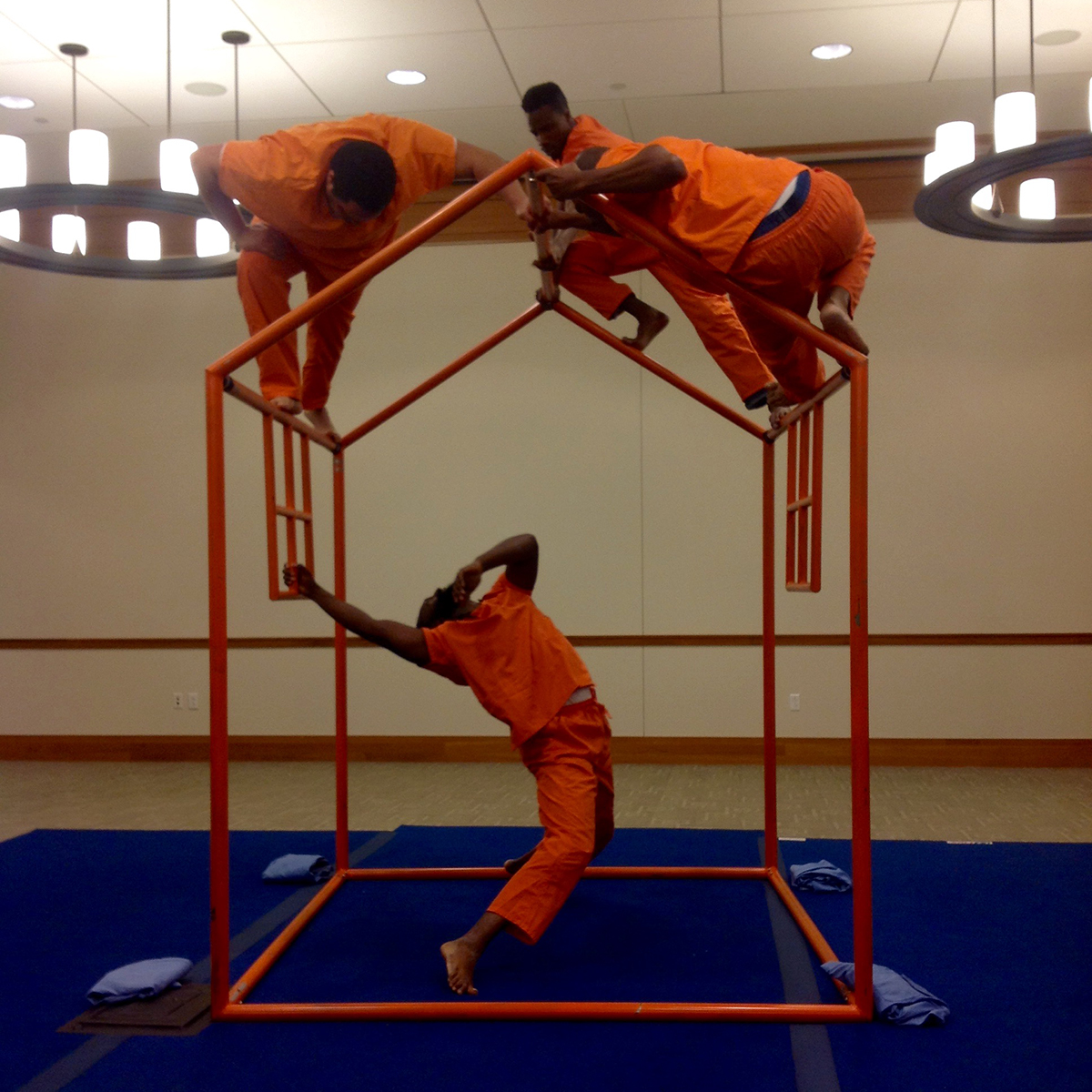

Members of the Zaccho Dance Company perform at Harvard Law School. Antoine Hunter (below), Travis Santell Rowland, Rashad Pridgen, and Matthew Wickett (above, left to right).

After the February 2012 shooting of Trayvon Martin, the hashag #blacklivesmatter took hold on Twitter and people took part in protests across the country decrying police brutality and the killing of unarmed black citizens. But it wasn’t only social media, marches, and protests that captured the historic moment, but many forms of art, as well.

“Art is a powerful entryway in the fight for justice,” explained David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice. On Friday, two days before the 50th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery march, the Institute brought the San Francisco Zaccho Dance Troupe to Cambridge, where Dying While Black and Brown, was introduced to a packed house at Harvard Law School.

The piece, choreographed by Zaccho’s artistic director Joanna Haigood, artistically spelled out the connection between incarceration, the death penalty, and unjust black and brown deaths—at least 56 unarmed black people were killed by police in 2014, more than all other races combined, and race plays a key part in which defendants live or die on death row.

Zaccho’s performance began with a score by noted jazz musician Marcus Shelby, as men entered and climbed onto a boxy jungle gym that looked like both a house and a cage at the same time. Each man represented a real person on death row, innocent or not, or a fictional creation based on parts of a real story. Trapped in the space, going nowhere, even when they rolled, somersaulted, fell, or fought each other on the blue mat, the men were always pulled back into the cage, a box that symbolized solitary confinement, death row, and the often silent victimization of black and brown men. The horror of slow motion movement on the bars, coupled with the trapped cries of “Can I get a phone?” and “Let me out,” were multiplied as the music became louder and no one could hear the prisoners, literally and figuratively.

At moments, the actors looked at their hands, as if they were examining their skin to see why they were the ones on death row. One man put his hands up, invoking #handsupdontshoot.

At one point, the men changed from their orange jumpsuits into blue jeans and light blue denim shirts, readying themselves for something ominous. One actor, who the audience discovered later was deaf, was led to his symbolic execution by two others, standing in for guards. The music stopped as the man’s breathing got faster and faster, a terrifying moment. The performer was led away, and then there were only three. The piece ended with a lonely figure looking at the audience through the bars.

Joining the actors and director Joanna Haigood for the discussion after the piece was Diann Rust-Tierney, Executive Director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. She pointed out that the Coalition wants to stop the death penalty around the country in states where it exists, and that they are 90 million strong.

“People are just beginning to make the connection between police abuse and executions,” she said. The dance is part of the Equal Justice Society’s campaign to restore 14th Amendment protections for victims of discrimination including those on death row.

Much like Common and John Legend’s anthem, Glory—the Academy Award-winning song from the movie Selma—the Zaccho Dance Troupe’s performance is an artistic work that speaks to the moment.

Black lives matter—even behind bars.