Playing Through the Pain

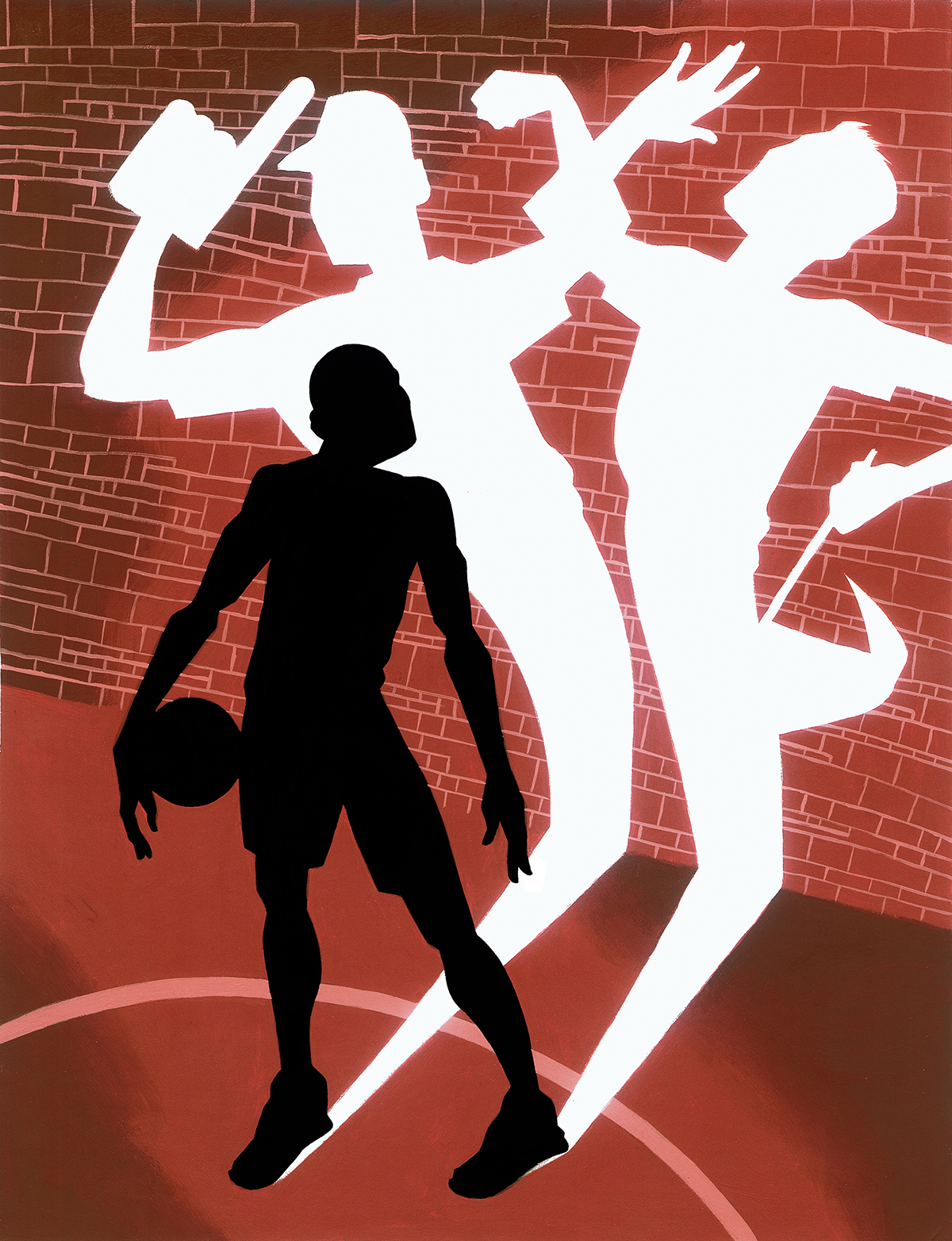

Illustration by Thomas Fuchs

A quarter of the way into his first season in Boston, things are going as well as anyone could have expected for Kevin Garnett. He’s got the Celtics off to one of their best starts ever, and after years of futility the team is considered a genuine championship contender. In the process, Garnett has been embraced by the city—fawned over and bragged about by fans and journalists alike. It’s been a pretty smooth ride. But it didn’t begin that way.

Just six short months ago, news of Garnett’s supposed feelings about Boston had the city cringing. I was in my car when it happened, listening as Michael Wilbon, the Washington Post columnist and cohost of ESPN’s Pardon the Interruption, spoke on Dan Patrick’s national ESPN radio show, putting the city on the defensive. Again. It was the day of the 2007 NBA draft, and Garnett was said to have opposed any trade from the Minnesota Timberwolves to the Celtics. This was before KG relented, of course, and people were imagining all kinds of reasons for his refusing to come here, chief among them the fact that the Celtics had been dreadful in recent seasons. But Wilbon was pretty sure there was more to it than that.

“First of all, it’s a bad team,” Wilbon opined. “Second of all, you have this history of bigotry against African-American people in Boston. The only place I’ve ever been confronted, multiple times, and been called the n-word to my face, is specifically the Boston Garden…. The fact is, Boston has that history, and black players know that, and they do not want to go voluntarily to Boston.” When asked by Patrick whether he thought that perception factored into Garnett’s unwillingness to be traded here, Wilbon said, “I know it does. Yeah. Sure. Absolutely.” He later added that racism “might have been our issue at one point, but now it’s [Boston’s] issue.”

There were qualifiers before and after those comments. Wilbon credited the Celtics for being one of the first teams in the NBA to feature black players. And he stipulated that he didn’t think Boston today is much different from other major cities. But that didn’t matter. All anyone heard was Wilbon calling Boston racist. And that’s all anyone needed to hear.

Not long after, Angels outfielder Gary Matthews Jr. weighed in with commentary of his own. “They’re loud, they’re drunk, they’re obnoxious,” Matthews told the Los Angeles Times, referring to Sox fans, and added that Fenway is “one of the few places you’ll hear racial comments.” It was an extemporaneous remark, one the reporter never asked him to elaborate on or provide specifics for—and as casually as it was thrown out, it was just as readily accepted as fact, with other national outlets, once again, quickly picking up the story. In that way, it smacked of a familiar pattern: Every few years, someone in the sports world comes along and says something similar. (Back in 2004, it was Barry Bonds telling reporters he wouldn’t play here because “it’s too racist.”)

Months after making his inflammatory comments, Wilbon tells me, “I wasn’t saying that Boston is a racist place. I was saying that this is a conversation that black people have. How separate are the worlds of black and white people for white people not to know that black people have this conversation? And not just black people but people of color. This conversation has been going on forever.” But that’s where Wilbon is wrong. We know the conversation goes on. It’s just that most people around here would rather not join in. Some recuse themselves entirely, some angrily dismiss the assertions, and still others run the other way, tossing denials over their shoulders: That’s not us. They don’t know us. I won’t dignify that. None of which is very effective when it comes to changing anyone’s impressions. Accordingly, just as people “know” it rains in Seattle, they’re certain Boston is racist.

So whatever you may think about Wilbon’s comments on the radio that day, he was right about one thing: It is Boston’s issue.

The Wilbon situation reminded me of what a friend from Dallas said before I moved here a few years ago. He’s a fairly big sports personality down in Texas. He also happens to be black, and he told me to watch myself in Boston, warning that anyone with “brown skin” isn’t welcome.

More than anything, we have busing to thank for that reputation. There’s no getting around it. Instead of inspiring racial harmony, the experiment failed miserably as white parents threw stones at busloads of frightened black children without compunction. Boston has been known ever since as the racist city of segregated enclaves like Southie and Charlestown.

Of course, other cities have been plagued by race problems, too. L.A. suffered the Watts riots in 1965, and those that followed the Rodney King verdict in 1992. Just last May, cops there violently broke up a peaceful immigration rally by using what the police chief later termed “inappropriate” force. In New York City, officers pumped 41 shots into unarmed immigrant Amadou Diallo in 1999.

More recently, the NYPD killed an 18-year-old mentally ill black man when officers mistook his hairbrush for a gun. And yet the issue of racism plagues Boston more than most. Somehow, it has become a part of the city’s identity.

As is so often the case in Boston, the incidents most passionately recalled are tied to sports. There’s the one about the Sox giving Jackie Robinson a tryout, then running him out of town, supposedly at the request of owner Tom Yawkey. The Red Sox were, infamously, the last team in the majors to integrate when they finally signed Pumpsie Green—12 long years after Robinson became a Dodger and, more important, a powerful symbol of change. Bud Collins, the legendary sportswriter who started out at the Herald in the 1950s, was once scolded for even suggesting that someone at the paper write about the Sox and racism. In his brilliant, brutally honest book Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston, ESPN’s Howard Bryant, who grew up here and worked as a sports columnist for the Herald, details the rebuke Collins received from his bosses: “‘They told me I had a lot to learn about their town,’ Collins remembered.”

The animus toward black athletes wasn’t exclusive to the Red Sox. Celtics Hall of Famer Bill Russell may have been named one of the NBA’s 50 greatest players, but that didn’t shield him from bigotry during his playing days. Russell, who once called Boston a “flea market of racism,” even had vandals break into his home just to defecate in his bed. His teammates also felt the hatred. “We were living in Framingham when I was a player,” recalls Celtics Hall of Famer K. C. Jones. “I went to buy a house about five blocks away…. The neighbors said they didn’t want any blacks to move into the house.” Another time, Jones applied for membership at a country club, only to be told they weren’t fond of “entertainers.” Still, Jones is quick to point out that he enjoyed his time in Boston, and that things have changed. He even calls me back to make sure I note that he harbors no ill will. He stresses this. But he also knows that the city’s racism didn’t end with him or Russell.

Red Sox outfielder Tommy Harper had an experience similar to Jones’s. In 1973, during spring training in Winter Haven, Florida, he and other black players were not invited to dinners his white teammates attended at a segregated local club. Twelve years later, while working as a member of the Sox coaching staff, he described the incident to the Globe. Within a year he was fired. He eventually brought a discrimination lawsuit against the club that resulted in a settlement. Not long afterward, Jim Rice—for years the lone black Sox player—supposedly told a young Ellis Burks to leave the city as fast as he could.

“Having gone to school up there for three years, it was always an issue, and there were places where you were told, ‘Don’t go,’” says NBA Hall of Famer Julius “Dr. J” Erving, who starred at UMass before becoming a Celtics antagonist with the New York Nets and Philadelphia 76ers. “Jim Rice and I were friendly, and we had racial discussions. It was this undertone more than anything blatant. It was rough up there for athletes.”

Even as late as the 1980s, the symbol for sports in Boston—and, really, the city as a whole—was Larry Bird’s Celtics. A team of predominately white superstars, the Celtics were seen as a counterbalance to Magic Johnson’s “Showtime” Lakers. That white fans in Boston and across the country rallied so passionately behind those Celtics, that they privately loved seeing a white team excel in a league consisting mostly of black players, rankled many African Americans. Former Detroit Pistons star Isiah Thomas drew the ire of many in Boston when he said that had Bird been black, he would have been just another good player.

Then there is former Celtic Dee Brown, who, after being drafted in 1990, was driving through Wellesley when he was pulled from his car by the police and held face-down on the pavement at gunpoint. The cops were looking for a bank robber. A black man.

And yet, like K. C. Jones, Brown doesn’t want anyone to get the wrong idea: He loves Boston. “One incident happens and people dwell on it. It happens in every city, but Boston is stigmatized by it,” Brown says. He repeatedly tells me that he has nothing but fond memories of playing here, that he wishes people would know the whole story before so quickly judging the city. “If you go back in history, especially with the Celtics, they had the first black player. The first black coach. There are a lot of things people forget to put in there. There are racial problems in every city. You go to the wrong neighborhood in any city and you’re black or you’re white or Hispanic or Italian or Irish, you might be in the wrong place.”

Despite defending Boston to anyone who will listen, and especially to me, Brown acknowledges that altering the perception of the city is a difficult task. He knows because he’s tried, making his case to players and journalists alike. He hasn’t gotten very far. Most of the bitterness toward Boston is so deeply rooted now that it feels almost impossible to change anyone’s mind. A lot of it goes back decades, festering for as long as some people have been alive. “People think the core of Boston is Italian and Irish,” Brown says. “The Celtic. The Patriot. The Tea Party. Paul Revere. It’s that history…. Being from Florida or the South, people would say to me, ‘Boston’s just like Up South.’ That’s what they called it: Up South.”