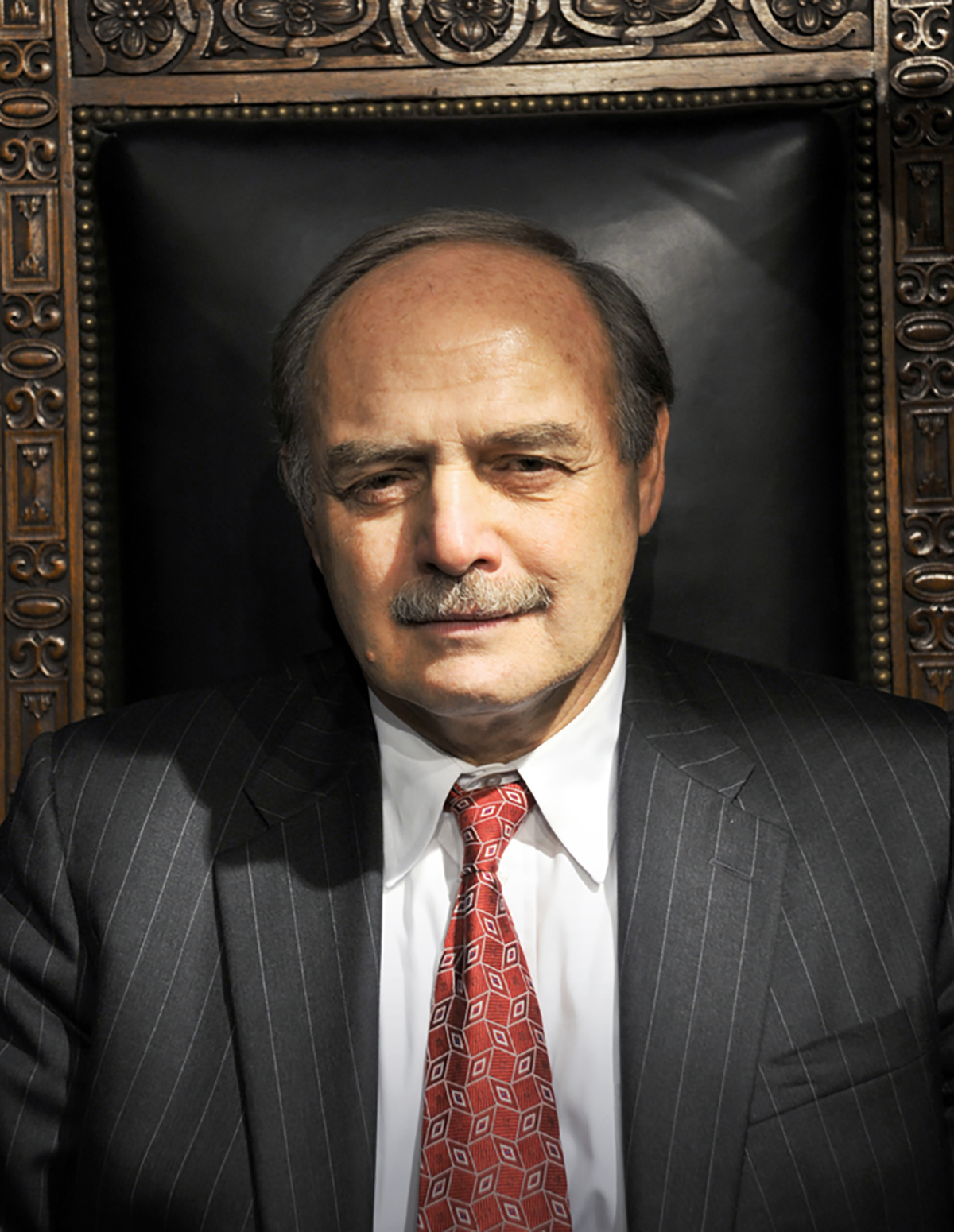

King Sal

Sal DiMasi, enthroned on the House speaker’s chair. (Photograph by John Goodman)

On Beacon Hill, Salvatore F. DiMasi is “Mr. Speaker,” but in the North End, he’s always Sal. Or, more accurately: Sal!!! Walking through his old neighborhood, he knows everyone, and everyone knows him. Because of this, he is obliged to frequently stop, hug, kiss, and shoot the bull. Oftentimes, the exchanges include policy advice, which DiMasi promises to mull over. Invariably, he finds himself buried in praise, moving through the streets in the same way he moves through the House chamber, as if on a wave of affection, pausing occasionally to slap his hand down on something—a table, a constituent, a colleague—and unleash a great, full laugh.

Back in December, DiMasi promised me an extensive tour of the neighborhood, but on the appointed day it was so cold, and he was so underdressed (overcoat, no hat, no scarf), that we were forced to duck inside repeatedly to warm up. Over cappuccinos at Caffè Graffiti on Hanover Street, he was holding forth on the government’s moral responsibility toward the downtrodden when he was interrupted by an old-timer who sauntered over and yelled, “I agree with your stance on the casinos! One hundred percent. But don’t tell Deval.”

“A familiar refrain!” DiMasi shot back, before assuring the table, “That wasn’t a plant.”

Earlier, we had crashed a bingo game at a community center on North Bennett Street. The senior citizens struggled to their feet to give Sal a standing ovation. As he bent down to kiss his well-wishers, one thrust a Christmas present into his hands (later revealed to be a homemade scarf). DiMasi introduced me, and delivered a well-worn line about how in the North End you didn’t have one mother, you had a hundred. One woman got so excited upon learning I was writing this article that she insisted on giving me a kiss, too. “Sal’s with us,” said Frank Romano, a neighborhood lifer lounging outside the bingo hall. “He’s a kibitzer. You stop anybody in the North End and ask them what they think about Sal, and you’ll never hear a bad word.” The man sitting next to him, Pete DeMarco, added, “He gets a lot of bad press. It’s unwarranted.”

Not that DiMasi cares much, one way or the other, about that negative coverage. It’s a small price to pay for the kind of immense clout he wields. DiMasi has been speaker for three years now, amassing a formidable record on big-ticket issues ranging from healthcare reform to gay rights to the state’s new energy policy, but if he’s known at all outside Beacon Hill, it’s as a mustachioed caricature clutching a gavel. His gruff voice, occasional disregard for enunciation, and effusive personality have given rise to the perception that he’s just a good-timer, a man who wants nothing more than to joke and golf his days away while padding his pension. (In fact, when a Globe columnist graded DiMasi’s first year running the House, the writer did it not by recapping his legislative record, but by detailing the improvement in his golf game: DiMasi had shaved two and a half strokes off his handicap.) That perception has fueled persistent whispers that he’s not long for the chamber, that he’s getting ready to bolt for a lucrative career in lobbying, or some such, rumors that boiled over last fall when the State House News Service published a list of would-be successors. Afterward, DiMasi was forced to publicly vow to remain speaker for a “long, long, long, long, long, long time.” (“I had a member call me the next day and say, ‘That’s it! He’s gone!'” says Representative Dan Bosley, a House ally.)

Beyond the glad-handing exterior, there isn’t much consensus as to who Sal DiMasi is, what he’s all about. His friends extol his humor and his commitment to social justice; his enemies paint him as a vengeful power whore. In fact, he’s both, as well as a quick-to-tears crusader for the poor and a stubborn fiscal hawk, and a consensus builder who steers the House with an eye toward minimal public conflict and an old-school brawler who revels in political blood sport. To get bogged down in those contradictions, though, is to miss the larger point. Above all else, DiMasi is a breed of politician Boston doesn’t see much of anymore: one that values pragmatism above ideology, and wields his power without apology. And it’s that, chiefly, that has placed him on a nasty collision course with Governor Deval Patrick, creating a dynamic that, more than anything else, will shape the direction of Massachusetts in the years ahead.

Last year was a rocky one for Patrick, the idealistic newbie who spent a considerable amount of his time being repeatedly hammered and outmaneuvered by DiMasi, often in ways seemingly designed for maximum humiliation. Patrick is new to government, something he parlayed into an advantage on the campaign trail, but DiMasi has been playing this game since Patrick was in law school and, as history has shown, doesn’t feel a particular need to kowtow to executive power—which means he’s not an easy man to sway, even with the most exquisitely crafted speeches and the loftiest ideals. The sooner Patrick resigns himself to this, DiMasi would have him believe, the easier things will get for him. If he tries to buck the speaker, well, things will just get harder. “There are people,” says a source close to the administration, “who believe [DiMasi] would not be unhappy if the governor were not successful, and everything returned to the way it was. The governor believes he has gone out of his way to be deferential to the speaker; I don’t think the speaker can say the same.” A second administration insider is even more succinct. The speaker’s single biggest point of contention with the governor, says this person, is that “he doesn’t ‘get it.’ Which means: He doesn’t do it Sal’s way.”

DiMasi, the House’s first Italian-American speaker, grew up next to the Old North Church in the North End, in a cold-water tenement heated by a kerosene stove in the kitchen. His grandparents lived downstairs. The toilet was in the hallway. The shower was two blocks away, at the neighborhood bathhouse. He says he started playing football and basketball in school so he wouldn’t have to feel ashamed about showering there.

“We used to play pimpleball against the church wall,” DiMasi says, standing outside his boyhood home. “Every time I walk through this fence, I feel like I’m going to get chased out by the vicars.” (The church long ago took its revenge: When Hurricane Carol hit in 1954, the steeple fell on top of DiMasi’s father’s car.) Back then, DiMasi says, “all the kids were afraid of our parents,” though it’s his grandmother who sounds particularly terrifying: “She could hit you with a shoe from 20 feet away. She was better than Tom Brady!” DiMasi wasn’t bad himself: Before an injury derailed his football career, he received a call from a recruiter representing Notre Dame—”back when that meant something.”

DiMasi returns to stories about his neighborhood often when explaining his political views. “If somebody was out of work injured, we’d bring food over,” he says. “When much has been given to you, much is expected for you to give in return. That’s what we do around here.” His friends and House colleagues frequently repeat this spiel verbatim, retelling the stories of Sal’s youth, and not a detail out of place. It’s become lore. But just because it’s well rehearsed doesn’t mean it’s an act. Jack Connors, the legendary cofounder of Hill, Holliday, and chairman of Partners HealthCare, saw firsthand DiMasi’s empathy when the speaker was brokering the state’s healthcare reform. “When people began to talk about what a difference this would make in the lives of those who didn’t have healthcare, I saw tears well up in his eyes. This is a guy who really cares. This is not some game he’s playing.”