The Race to Save the Rare Books

Photograph by Christopher Churchill

Go in past the bronze statues that guard the entrance of the Boston Public Library, up the grand staircase and around the marble lions commemorating a pair of Civil War regiments. Go up to the top of the stairs, to the landing, where the full grandeur of art and architecture hits you with the sense that this is a place that matters.

But it is also a place in trouble. So keep going.

Up another flight of stairs, down increasingly dusty corridors, across worn carpeting, and toward the double doors of the library’s rare books department. Step through them and into the soft, dim glow that protects the treasures displayed there in glass cases: some of the oldest and most valuable books on earth.

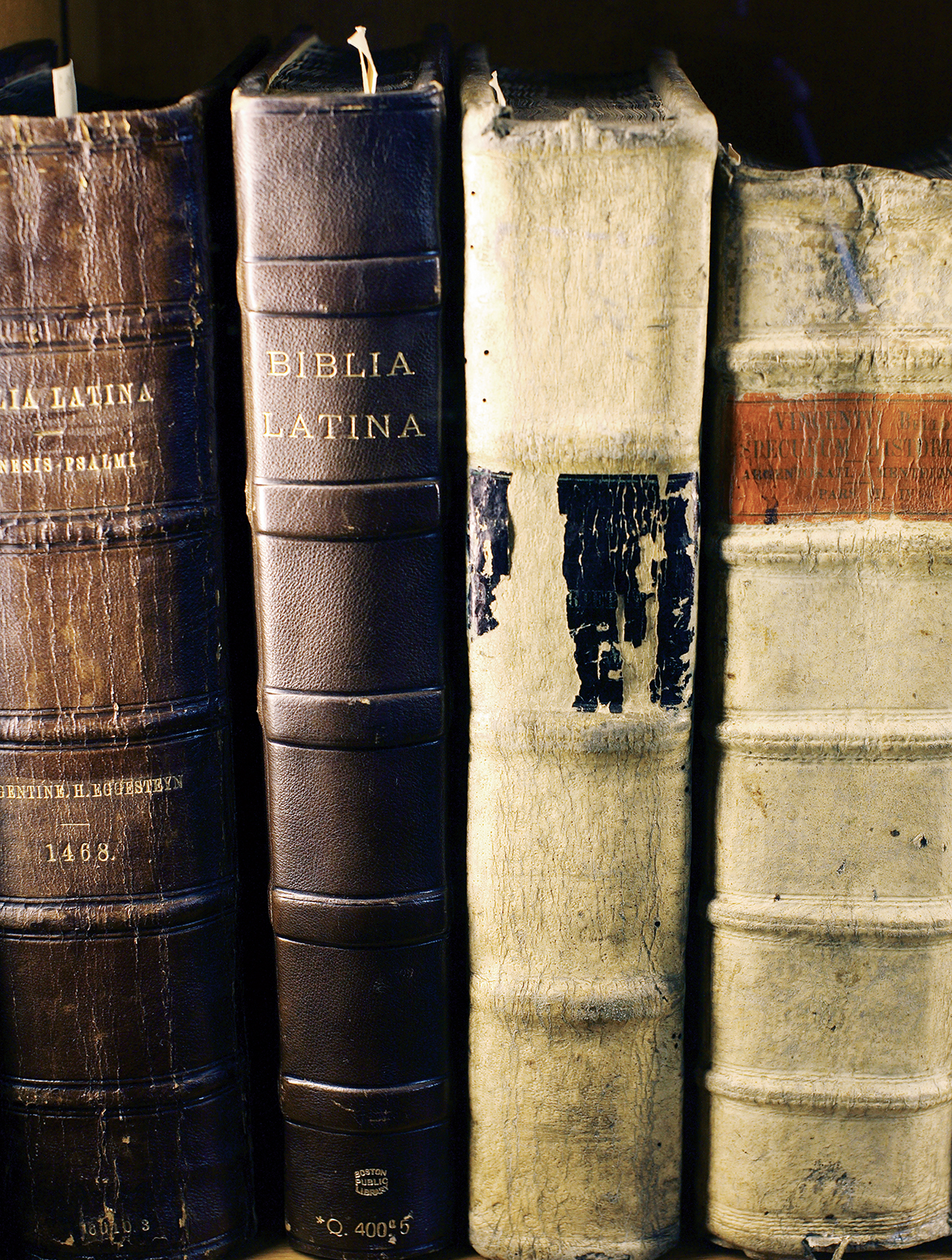

On the left of the room, scores of incunabula—books published before 1501—are shelved in neat rows. Each of these volumes, born at the dawn of the printing age, is priceless; the library boasts more than 500. Above, along a balcony that encircles the room, the personal library of President John Adams looms out of reach. Composed of some 3,510 volumes, it was among the great collections of its day—and, as one of the few 18th-century libraries still intact, would be a stunning prize for the library even if its provenance could not be traced to one of the country’s founding fathers.

Here, in this low light, a visitor is a world away from the crammed shelves on the airy floors downstairs. Some of these volumes are huge folios, others octavos small enough for a pocket or purse. Their leather bindings peer from the past like the bodies of the mummified popes that look out from their glass altar-caskets in the Vatican. Unlike the popes, though, these books are still alive.

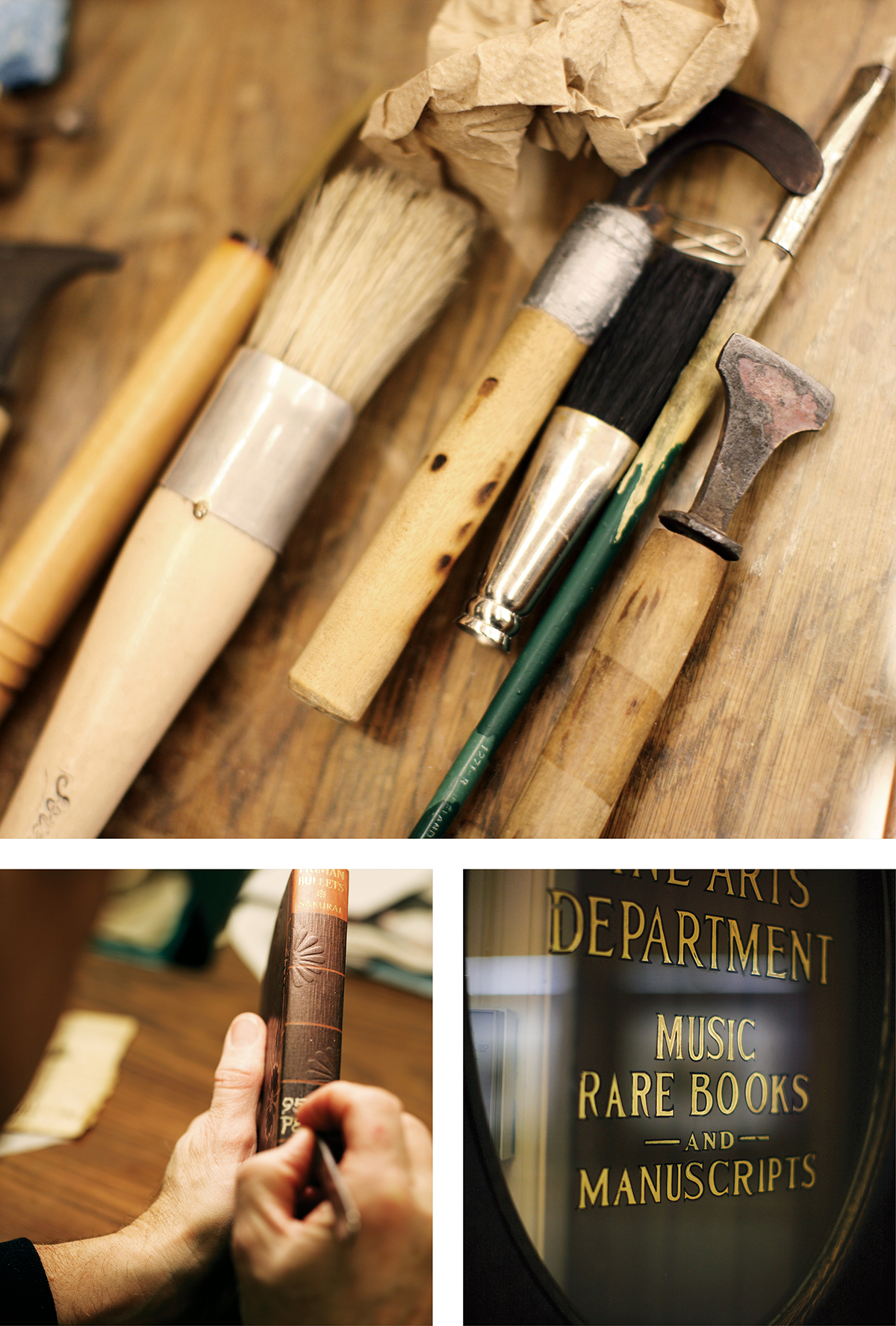

And for that, you have Stuart Walker to thank. The library’s conservator of rare books is in his workroom, just to the left of the display space. It’s the windowless sacristy to this sanctum of books, and also a battlefield where, every day, Walker fights acid, mold, and all the other insidious enemies that the passage of time is using to destroy the library’s treasures. The lab is spartan: four sinks, two light tables, a book press that calls to mind a medieval torture device. His tools are rudimentary: a variety of chemicals; a few dozen sheets of Japanese paper called tengujo, used for fixing torn pages; an array of needles and threads, for the meticulous task of resewing bindings.

Walker has been with the library since 1982, when he was hired through a grant to oversee a restoration project. When it ended, the BPL kept him on board. At 59, he has the calm, no-nonsense demeanor of someone who puts on his blue apron every morning and gets down to business. But he’s a bit nervous today. He’s running filtered water into a large bowl, which is overflowing into an even larger tray. He’s about to wash a book.

Stuart Walker, the library’s conservator of rare books. (Photograph by Christopher Churchill)

Near Walker’s sink sits Volume II of A History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, published in England in 1786 by a Unitarian named Joseph Priestley. It’s in pretty rough shape. The edges are so flaked that flipping the book open produces a puff of paper dandruff. Its pages are pulling apart at the gutter. And it looks as though it’s been defaced, the margins covered in pen scratchings.

But it’s those notes that make the Priestley book worth worrying about, because they were written by John Adams. When he read, he used the margins of his books to carry on a personal dialogue with authors who pleased him or piqued him. More than two centuries later, we can still eavesdrop on the conversation—so long as Walker doesn’t screw up. He knows that plunging the pages into water will remove the ancient glue and chemicals that are destroying them. The risk is that it will wash away Adams’s notes, too.

A caretaking effort like this is part of the mandate that brought the four-volume Priestley here in the first place. The trustees of the Adams estate transferred the collection from the Thomas Crane Library in Quincy, where it had been held, to the BPL in 1894, figuring the library’s yet-unopened Copley Square location would be a better facility for safeguarding the national treasure. But in 2005, when the BPL’s Adams curator, Beth Prindle, was preparing the first public exhibition of the president’s library, she opened the first Priestley volume to find that the marginalia was flaking away. Prindle rushed the book across the hall to Walker, whose reply was simple: “This can’t happen.” He laid out the crumbling bits of paper and carefully fit Adams’s brain droppings together like a jigsaw puzzle. Then he restored the whole book so that it was ready to display.

Three years later, Walker’s only now getting around to volume II. A manpower shortage is the problem. Once, there were six people in his department. But over the past two decades, budgets have been slashed, so that today it’s just Walker and assistant conservator Albert Lizotte. The dwindling resources make for an ironic footnote in the dustup over the ouster of the library’s president, Bernard Margolis, who, it was said, lavished too much attention on the central library—on collections like John Adams’s—at the expense of the neighborhood branches. Not that Walker has time to worry about political spats. Untreated, the Priestley book will grow brittle; Adams’s scrawled notes will break apart and become lost for good. And of course, that’s just that one volume. The story is the same with scores and scores of books desperate for Walker’s care.

Clockwise from left, some of the tools of Walker’s trade; a door sign on the path to the rare books department; Walker using a scalpel to remove paint from a book’s spine. (photographs by Christopher Churchill)

Rescuing the BPL’s rare books is a job of jaw-dropping proportion. Including those on display, the library holds half a million titles and a million manuscripts. The most valuable aren’t the ones on view on glass-fronted shelves. Interested in The Bay Psalm Book, the first book printed in North America? The library’s got two. Want to see the handiwork of Johannes Gutenberg, the father of modern printing? The BPL has a page from his Bible, and one of the few copies of his Catholicon. Shakespeare? Unless you have a really good reason, you probably won’t get to see the famed 1623 First Folio, the original collection of his plays. That one’s kept in a vault.

Most of the rare books arrived in the late 19th century, back when Boston was the Athens of America, back when Bostonians were building a new home for their public library (the nation’s first), founded in 1848. Vivian Spiro, chairwoman of the Associates of the Boston Public Library, a group that raises funds for the library (and to which, full disclosure, I belong), puts that 19th-century giving into 21st-century perspective. “The optimism that made the creation of the BPL possible,” she says, “is now responsible for its predicament regarding the conservation of its most important holdings.”