Busted

Illustration by Sean McCabe

Boston Police Commissioner Ed Davis sat in a small hotel room at the Sheraton in Revere, surrounded by FBI agents and police officers assigned to the BPD’s anti-corruption unit. The room, dubbed the OP, for “operation post,” was cramped and sweltering, and made only hotter by the high-tech audio and video equipment running in it. Davis, a hulking man, tugged at his blue button-down shirt, loosened his tie, and anxiously settled in. The OP was mostly quiet, save for the occasional crackle of a police radio with a transmission from the surveillance team. For eight months, its members had been following one of their own, a Boston cop named Jose Ortiz, and today, May 2, 2007, the department was going to move.

On the roof of the Sheraton, FBI sharpshooters covered an informant who was waiting for Ortiz to pull into the parking lot to take control of a cache of drugs and money. But it wasn’t just the informant the cops were concerned about. Sometimes dirty cops eat their guns when they’re captured, and everyone assembled at the hotel that afternoon wanted to see Ortiz in handcuffs, not a body bag.

“There he is,” said an agent. Davis looked out the window and saw Ortiz, a 20-year BPD veteran, swagger across the parking lot. Just off working a paid detail, he was wearing a black fleece over his uniform shirt, but the navy blue pants with the light blue stripe were easily recognizable as standard department garb. Anyone passing by might have wondered what a Boston cop was doing at this Revere hotel, but not the crew manning the OP: They knew he was looking for the four kilograms of cocaine and $4,000 in large bills that were stashed in the trunk of a blue sedan.

The case against Ortiz had begun on August 30, 2006, when the cop was caught on a security tape coming into the Boston business of the informant, who the feds now call “Victim A.” According to the FBI’s account of the meeting, later filed in court, Ortiz announced he worked for “Colombian people” who wanted Victim A to pay off an alleged drug debt of $265,000. I’ll kill you and your family myself, Ortiz said. He said he knew where Victim A lived, who his family was, who his friends were. Then, the FBI says, Ortiz gave Victim A his Boston Police Department business card. On the front was the phone number to his station house, District 4 in the South End. On the back he scrawled his nickname: El Flaco (“The Skinny One”). As Ortiz prepared to leave the store, he said the man should ask for him by that name when he called.

Victim A decided to report the incident to the authorities. The following day, he handed over the business card to Boston police officers in the anti-corruption unit, a small, elite group charged with investigating major crimes within the department. The cops put together a photo lineup of eight men; after Victim A immediately pointed to Ortiz, the FBI and BPD used him to set up a sting. For the next few months, Victim A would meet Ortiz at detail sites, several times pressing thousands of dollars into the hands of the cop, who always wore his BPD uniform. During one phone call recorded by the feds, Ortiz warned Victim A that if he did not pay the full amount the Colombians said they were owed, they might “become very aggressive.” “[If they] can’t get their money back,” Ortiz told the man in Spanish on another call, as investigators listened in, “they are going to have to resolve the problem themselves. You understand me? And that, that is what we are trying to avoid.”

Not surprisingly, Victim A was nervous as he waited in the parking lot of the Sheraton, even with the sharpshooters overhead. Davis watched as the pair talked. His Spanish wasn’t good enough to make out what was being said, but he had been at enough narcotics buys to know what was about to happen. Victim A opened the trunk. Ortiz saw the drugs and cash that together were to pay off the last of Victim A’s debt, and nodded and smiled. “It was nauseating to see this guy show up in a uniform with a jacket over it to participate in what was a drug deal,” Davis says. “It was sickening to see somebody who would sell his badge like that.” Victim A handed Ortiz the keys to the car. Within moments the FBI SWAT team swarmed from their hidden positions and surrounded him.

“I’m a cop!” Ortiz screamed, as he was forced to his knees, his hands in the air. The FBI agents cuffed him and pushed him down onto the pavement. Ortiz tried again: “I’m a cop!” But this time, for the first time, that would not be enough to help him get off easy.

After Ortiz went down, Ed Davis joined Lieutenant Detective Frank Mancini, the arresting officer from the anti-corruption unit, in the room where Ortiz was being questioned and booked. For a minute or so, Davis glared at the disgraced cop in his BPD blues. Then he tore the badge off Ortiz’s chest, snapping, “You are no longer a Boston police officer. You don’t deserve to wear this.”

But Davis now admits that Ortiz should have had his badge confiscated long before that day. Prior to his arrest, Ortiz had been suspended from the force six different times, for offenses that included swearing at a commanding officer, lying on police reports, double dipping into overtime, and stealing a sheet from a fellow officer’s citation book to write a bothersome neighbor an illegal ticket. Yet for all these violations, Ortiz was never severely punished. The most serious disciplinary action he received was for forging detail slips, for which he got a 70-day unpaid suspension. And even then he served only 20 days.

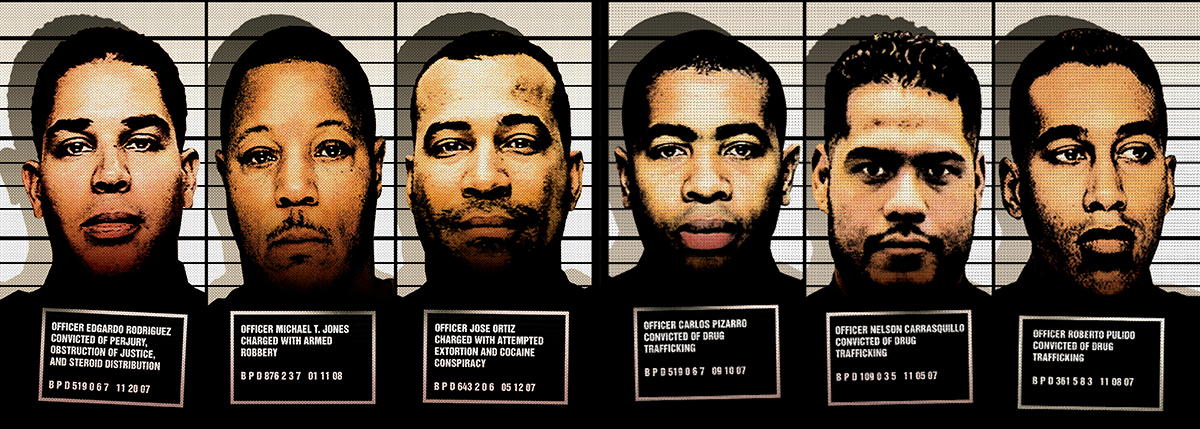

Worse still, even if everything the FBI says is true, Ortiz is far from the only strike against the BPD, which has seen its reputation sullied by a string of recent scandals: Officer Edgardo Rodriguez pleads guilty to lying to a federal grand jury and distributing steroids. Officer Paul Durkin shoots a cop buddy who tried to take his keys after a night of drinking, and is forced to resign. In January, veteran officer Michael T. Jones is arrested for allegedly robbing a Roslindale gas station at gunpoint. The next month, detective Kevin Guy, a longtime narcotics cop, is hit with a 45-day suspension after testing positive for steroids. Two officers, Windell Josey, who worked with domestic violence victims, and David Murphy, are nabbed by other police departments—one in Randolph and one in Baltimore, Maryland—for allegedly assaulting their girlfriends. At the department’s Hyde Park evidence warehouse, a facility only cops are allowed into, a probe finds that drugs from nearly 1,000 cases spanning 16 years have been stolen or improperly discarded.

Now, many law enforcement officials are bracing for the final sentencing hearing for a group of disgraced cops known in the department as “the Three Amigos.” All three officers pleaded guilty to drug possession and trafficking charges. One of them, Carlos Pizarro, was sentenced to 13 years in federal prison in December. Another, Nelson Carrasquillo, was sentenced to 18 years last month. According to court documents, the suspected ringleader, Roberto Pulido, was also accused of (though never charged with) involvement in an identity fraud ring and helping to run an illegal after-hours club in Hyde Park, where strippers would perform lap dances for cops in a closed area called “the Boom-Boom Room.” He is likely to receive his term in the coming months. Meanwhile, even more sordid revelations may soon emerge. Boston magazine has learned that Pulido’s 2002 shooting at the hands of a shadowy assailant will also be reviewed. And the U.S. Attorney’s Office has initiated an investigation into allegations of widespread steroid abuse in the BPD.

As the outrages pile up, Ed Davis is struggling to fulfill his pledge to wipe the dirt from the department he took over in 2006. Unfortunately, in Boston, ripping a badge off a corrupt cop is the easy part. Actually getting the cop off the force is something else altogether. In part because of shoddy management, and in part because of a system that makes it exceedingly difficult to eliminate bad seeds, reform efforts start off at a serious disadvantage to entrenched dysfunction. The problems run deep, and by the looks of things, the worst may be yet to come.