The Girl Who Cried Wolf: A Holocaust Fairy Tale

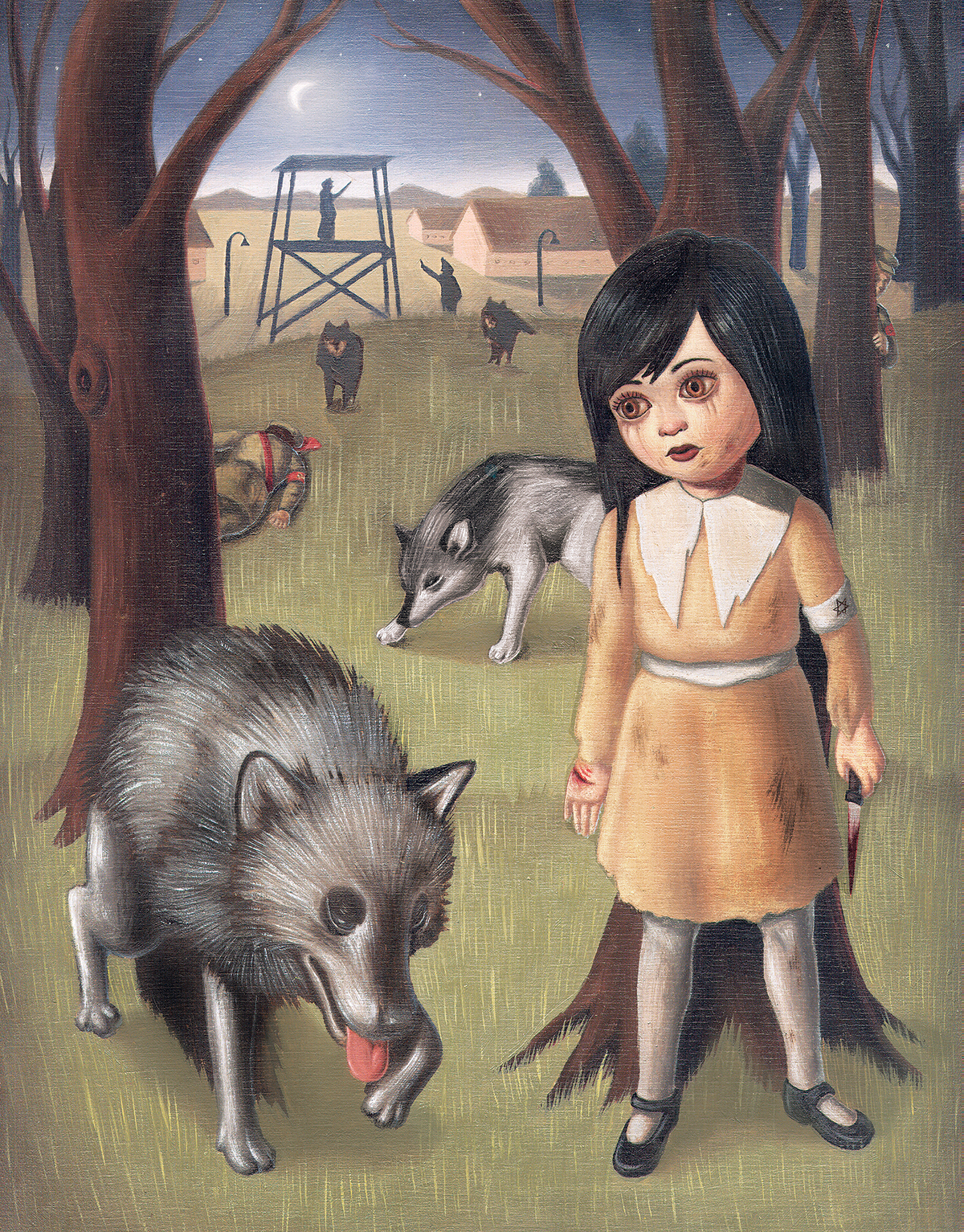

Illustration by Ana Bagayan

On a crisp autumn afternoon in 1997, Monique “Misha” Defonseca drove from her house in Millis to Wolf Hollow, a wildlife center in Ipswich. She was going there to demonstrate how humans and wolves can live in harmony. In the popular imagination, wolves are vicious predators, but at Wolf Hollow they talk about how wolves are intelligent, social creatures that have more to fear from humans than we from them.

Defonseca was living proof of Wolf Hollow’s message: A few months earlier, she had gone there to sign copies of her new book, Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years, which tells the story of a Jewish girl from Brussels who, at the age of seven, loses her parents, runs away from the family that takes her in, and walks for thousands of miles by herself, all the way from Belgium to Ukraine, while evading the Nazis. Along her perilous journey, she stays with a pair of wolves she names Maman Rita and Ita, and later joins a pack of six adults and four pups. “I was like the wolves, a hunted animal, one that would be killed on sight,” Defonseca writes in Misha. Later in the book, she says, “I have no idea how many months I spent with them, but I wanted it to last forever.”

The book signing back in May had attracted 300 people curious about Defonseca’s incredible story, but this return visit had the potential to reach many more: It was being taped for Oprah. For the segment, Defonseca would go inside two layers of chainlink fence and cavort with wolves once again. Joni Soffron, who runs Wolf Hollow with her family, brought together submissive members of the center’s pack in one of the pens. She gave Defonseca some cubes of cheese to feed them, and told her to crouch down and keep her head as low as theirs.

The Oprah taping had also lured Defonseca’s publisher, Jane Daniel, to Wolf Hollow. Defonseca had a stormy working relationship with Daniel, but the day’s events could not have happened without her. It was Daniel who persuaded Defonseca to turn her wartime memories into a book; Daniel who sought out Soffron at Wolf Hollow; Daniel who engaged a publicist to pitch Misha to Oprah. In its first six months, Misha sold a few thousand copies—not terrible for a Holocaust memoir from a small-time publisher, but not enough to make anyone rich or famous. Still, Misha told a story that could resonate with Oprah‘s audience: a child victimized by adults, a Jew on the run from Nazis, an animal lover who found refuge from the depravity of humans in the embrace of wolves.

Inside the pen, the wolves approached Defonseca and nibbled on the cheese. “The connection they had with each other was immediately like something I had never seen with anyone else,” says Soffron. Then a male named Petro got up on his hind legs. Catching a whiff of Defonseca’s hairspray, he opened his jaws and put them around her head. Soffron understood this as a signal of acceptance from Petro, but to anyone less familiar with wolves, it looked as if he were about to bite Defonseca. When Petro let go, one of his fangs scraped her ear and drew blood. The cameras stopped. Defonseca stepped out of the pen and cleaned up her injury. It wasn’t a serious wound, and everyone else appeared more shaken than Defonseca, who went on to answer the Oprah producer’s questions for an hour. At the end of the session, Defonseca howled. Petro and the others howled back.

It seemed like only a matter of time before an Oprah appearance would put Misha on the map. But Defonseca never sat down with Oprah Winfrey in the studio, and the footage from Wolf Hollow never aired. Daniel says Defonseca sabotaged herself by being uncooperative with the show’s efforts to set up her trip to Chicago, and by coming off as too coarse and combative in a subsequent phone call with a producer. (According to Daniel, Defonseca asked if they wanted to film her peeing with wolves, too.) Defonseca, meanwhile, blamed her publisher for failing to follow through on the session at Wolf Hollow, and a judge would concur, identifying the incident as part of a larger scheme by Daniel to take advantage of a Holocaust survivor. Whatever happened, it was for the best. It meant the audience of America’s most popular daytime talk show was never exposed to Monique Defonseca’s lies.

I first heard about Misha two years later, in 1999, at a conference in Prague for child survivors of the Holocaust. I was there researching a book I was writing about a man who called himself Binjamin Wilkomirski. He had drawn upon my own family history in creating an identity as a Jewish child survivor of the Holocaust, claiming kinship with an Avram Wilkomirski of Riga, Latvia, who was my great-grandmother’s brother. My family learned of Binjamin after he published a memoir, Fragments, which won the 1996 National Jewish Book Award for Autobiography and Memoir, and similar prizes in England and France. By the time I arrived in Prague, however, Fragments had been exposed as a hoax: Binjamin was in fact a Catholic from Switzerland named Bruno, who’d indeed had a tumultuous early childhood—abandoned by his father and mother, maltreated by a foster family, and finally adopted by a wealthy Zurich doctor and his wife—but had never encountered the Nazis, let alone spent time in concentration camps, as he claimed.

My interest in a phony Holocaust survivor was not always the best conversation starter at a conference of authentic ones, but one child survivor I managed to meet there suggested I look into Misha. Back home, I ordered a copy and found it unbelievable. There were similarities to Fragments: the lurid specificity of the violence as contrasted with the vagueness of basic information; the breadth of the narrator’s experiences, which encompassed the entirety of the Holocaust. Then there was the tiny compass embedded in a cowrie shell (a photo appears in Misha) that Defonseca says she used to find her way east—an Eagle Scout would have a hard time navigating with this souvenir. She said she had stabbed to death a German soldier twice her size whom she had just seen rape and murder a young woman. And claimed that she had snuck into the Warsaw Ghetto, and, even more extraordinary, snuck out. And that she had lived with wolves, not once but twice.

But even if the memoir was implausible, Defonseca could still be a Jewish child survivor of the Holocaust. As long as she insisted on her memories, the only way to expose Defonseca would be through hard evidence: wartime records, photographs, genetic samples. To learn more about Misha, I wrote to Holocaust scholars, hidden-child groups, and municipal archives in Brussels, to little avail; Belgium has strong privacy laws that protect personal records. And when I raised the question of authenticity with Ramona Hamblin, a lawyer who at one time represented Defonseca, she argued that the core of the story was true, and that anything dubious about Misha was an embellishment or misrepresentation not by its author, but instead by her publisher, Jane Daniel. Hamblin clearly did not want Defonseca to be discussed in the context of Binjamin Wilkomirski, and sent letters to me and to my editor in an attempt to persuade us to leave her client out of the book I was writing about him. “It is not only unfair to cast aspersions on Misha for [Daniel’s] overreaching acts of censorship, it is dishonest,” Hamblin wrote. My book A Life in Pieces came out in 2002, with only a brief discussion of Misha, and many unanswered questions.

According to Misha, Defonseca arrived in the United States in December 1985 “with my husband, my son, and all my pets.” Maurice Defonseca, a Belgian who’d spent his career working for the computer firm Honeywell Bull, had just been transferred to an executive job in the Boston area. According to one friend, the couple had met while she was working as a receptionist at Honeywell Bull in Brussels. (The Defonsecas declined to speak on the record for this story. Maurice told me his wife is undergoing therapy and is unable to talk.) The Defonsecas bought a house in Millis in 1985. Though her first name was Monique, in America she went by Misha. Before Maurice, she had been married to a Belgian named Morris Levy, and she often used Levy as a middle name, bolstering her Jewish bona fides. “We went to her bat mitzvah, we’ve gone to her house to celebrate Yom Kippur,” says Valerie Sullivan, whose late mother, Odette, counted Misha as a close friend.

The Defonsecas joined a Conservative synagogue, Temple Beth Torah, in Holliston. “She said she was a survivor. She was obviously very traumatized, but she had never talked about it,” says Rabbi Joanne Yocheved Heiligman, who spent two years at Temple Beth Torah. “She wasn’t pushing to tell the story—she told the story when I asked her.” In 1989 or 1990, Defonseca told Heiligman that she had been “saved by animals.” It was an amazing tale, but there are many stories of improbable survival from the Holocaust: “I have a cousin who rode around Europe under railroad cars,” the rabbi says. A couple of weeks later, Heiligman invited Defonseca to ascend the bimah—the platform from which the Torah is read—on Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, and bear witness in public for the first time. The congregation lit six memorial candles; Defonseca made the unusual request that one be dedicated to the animals. The rabbi acquiesced. She says the congregation found it moving.

Those who know Defonseca mention her strong French accent, penetrating blue eyes, and penchant for speaking her mind, but what comes up most often is her connection with animals. “She loves them; they love her,” says Sullivan. “I’ve recovered birds that are injured, and she’s brought them back to health.” Descriptions of the Defonseca home in Millis tell of a house overrun with animals—many cats, a few dogs—and a yard given over to wildlife: raccoons, squirrels, skunks. “She doesn’t like people. She’d rather be around animals,” says Heiligman.

It was Defonseca’s love for one particular animal that brought her into the orbit of Jane Daniel. Separated, with two grown children, and living in Newton, Daniel had worked in marketing and had also done some freelance writing. In 1990, Daniel wrote How to Protect Your Life Savings from Catastrophic Illness and Nursing Homes with Harley Gordon, a Boston lawyer, and published the book herself. When bookstores showed little interest in stocking it, Gordon and Daniel set up a toll-free number and marketed it themselves. The book started to sell, and Simon & Schuster offered to take it on. But having borne all the risk, the duo did not see any reason to share the rewards. “A contract with a publisher,” she told the Boston Globe at the time, “means that everything is entirely and exclusively for the benefit of the publisher.” How to Protect Your Life Savings also attracted the interest of Cleveland attorney Armond Budish, who noticed that some of the charts that appeared in his how-to book also appeared in Gordon and Daniel’s. In 1992, a judge ordered Gordon and Daniel to take their title off the market. They did, then sued their own lawyers for malpractice.

The drama over How to Protect Your Life Savings did not scare Daniel away from the publishing business, however. In 1993, she set up an imprint called Mt. Ivy Press, running it out of her Newton home, and put out a few titles: Weddings for Complicated Families, Main Dish Salads, and Gigolos: The Secret Lives of Men Who Service Women. At the same time, Daniel began doing public relations for Play It Again Video, a Needham company that strings together family photos into multimedia slide shows. When Daniel asked Play It Again what its most memorable project had been, her client told her about a two-and-a-half-hour memorial video for a terrier named Jimmy. It had been commissioned by Jimmy’s owner, Misha Defonseca.

Daniel arranged to meet Defonseca at a restaurant in Sherborn in 1994, hoping to pitch the Jimmy video as a newspaper story that would give Play It Again some exposure. As they talked, Defonseca told her how she had survived the Holocaust by walking across Europe and living with wolves. Daniel said she thought it would make a great book.

Though Defonseca had given talks locally about her wartime ordeal since coming out at Temple Beth Torah, she told Daniel she had no plans to write a memoir. Still, Daniel persisted, and, after several visits to the Defonsecas in Millis, she managed to sign her up. Mt. Ivy did not offer Defonseca an advance, but the contract guaranteed royalty payments and a share of film and foreign publishing rights. To get around the obstacle of Defonseca’s limited English, Daniel asked her friend and next-door neighbor, Vera Lee, to work on the project with her. Lee, who had taught French at Boston College and run the French Library in Boston, wouldn’t get paid up front for interviewing Defonseca and writing a manuscript based on their conversations, but she would share the copyright and the proceeds. While all three women would invest their time in Misha for an uncertain reward, Defonseca’s singular story seemed to have more commercial potential than Main Dish Salads.

Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years came out in early April 1997, with blurbs from leading Jewish figures; Elie Wiesel, for one, called it “very moving.” Working with Elaine Rogers at the Boston literary agency Palmer & Dodge, Mt. Ivy sold a one-year film option to Disney before publication. By the time Mt. Ivy put out Misha, Palmer & Dodge had also sold the foreign rights in several countries, including a six-figure deal for the German edition. Defonseca retained the French rights and crafted a second version of her life story that was published in France later that year. It went on to become a bestseller.

The making of Misha was not without complications. “Misha actually didn’t have that much concrete to put into the story, not enough to make a whole book,” Lee told me in 2001. In an effort to put together a coherent narrative, Lee created scenes out of remembered tidbits, entire conversations out of snippets of dialogue, she said. She read up on the wildlife and landscape of the places Defonseca passed through—France, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, Italy—and on the behavior of wolves. When Lee finished a chapter, she would share it with Daniel. By May 1996, a rift had emerged. Lee said Daniel wanted the story to be more lyrical and to include a romantic interest for young Misha; Daniel thought Lee’s manuscript was too short, the tone too juvenile. Ultimately, Daniel took over Misha, re-interviewing Defonseca and reworking large sections of the text herself.

In the months before she published Misha, Daniel heard concerns about the authenticity of the tale. Henryk Broder, a German journalist, wrote a skeptical article for the newsweekly Der Spiegel. In Daniel’s quest to gain blurbs, she had sent the manuscript to academics and historians, including Debórah Dwork, the author of Children with a Star: Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe. Dwork told me: “It wasn’t that there were numerous inaccuracies. It’s that I thought that the whole thing was a fantasy.” That’s not what Daniel heard; she wrote Dwork to thank her for “del

ivering the most embarrassing moment of my publishing career,” made a few corrections, and blamed any errors on Vera Lee. In a December 1996 letter, Daniel offered Lee the choice of getting paid and taking her name off the book, or withdrawing her contribution to the manuscript. But neither option was acceptable to Lee, who decided to hire a lawyer.

In May 1998, Lee filed a breach-of-contract suit. At first, she went after both Daniel and Defonseca, but Defonseca soon aligned herself with her former coauthor, deciding that Daniel had treated her unfairly. When Daniel had taken over the manuscript, she added Mt. Ivy’s name to the copyright. Mt. Ivy in turn channeled foreign rights payments to an offshore corporation called Mt. Ivy Press International, based in the Turks and Caicos. Daniel insists there was nothing improper about the offshore corporation—she says she set it up for tax purposes—but its existence was among the reasons a jury decided in August 2001 that Daniel and Mt. Ivy had withheld royalties from Defonseca and Lee, and had caused Defonseca “severe emotional distress.” The court ordered Daniel to pay $7.5 million to Defonseca, and another $3.3 million to Lee.

By all accounts, the Defonsecas seemed to need the money. Maurice had left Honeywell Bull back in 1988; Der Spiegel would later report that he was laid off after receiving his green card. The precarious finances of the Holocaust survivor and her husband became part of the story behind the story as the publication date neared: The Defonsecas were said to be receiving donations of food and pet care from neighbors, and one generous Millis resident had recently loaned them $5,000 to fend off foreclosure. Stan Kizlinski met Maurice in a state-funded networking group. “We were all out of work at the time,” says Kizlinski. “Maurice and I got to be friends.” One day, “Maurice gave me a call and said they needed money to help meet their house payments until Misha’s royalties came in.” In April 1997, Kizlinski loaned the Defonsecas $1,000; they paid him back $200.

When Lee filed her lawsuit, it froze all business activity involving Misha. With no money coming in from the book, the Defonsecas asked for more help. The president of Congregation Agudath Achim in Medway circulated a letter on behalf of the Defonsecas in 1999. “Misha is in very poor health and her financial situation is dire,” it stated. “She is currently offering her furniture for sale just to survive.” The entreaty described a clear villain: Jane Daniel, who “refuses to even give Misha a case of books that Misha could sell and get money for food and gas.” It also mentioned offers for the film rights to Defonseca’s story, including one for about $1.5 million. “However, Misha cannot enter into any deal until the rights to her story are clear.” In February 2001, the Defonsecas filed for bankruptcy. They were $36,000 behind on house payments and owed money to credit card companies and department stores, as well as a handful of neighbors in Millis.

Defonseca continued to find people willing to come to her and her husband’s aid. Karen Schulman, a former medical secretary, was at work at a CVS in Medway in 2001 when a customer told her that the Defonsecas didn’t know where they could go with their two dozen cats and two dogs. Schulman, who is Jewish but not a practicing Jew, had heard the story of Misha. She offered the Defonsecas four rooms in her ranch-style house in Milford. “I told them they would stay with me as long as they needed,” says Schulman. “I never wanted a dime, but they insisted on giving me $500 a month. We would see each other in the kitchen, occasionally have dinner. They would speak French, they would eat, go back to their room. They were very private.” Schulman bought a carpeted tree for the Defonsecas’ cats; the Defonsecas fed the Schulmans’ miniature schnauzer. In August 2001, Schulman drove with the couple to the courthouse in Cambridge for the trial over Defonseca’s book, and sat in the gallery to support her.

Schulman would also sometimes chauffeur Defonseca to Walpole State Prison, where Defonseca talked with her friend Joe Labriola, serving life for a drug-related murder he insists he did not commit. They had met while Defonseca visited Norfolk Prison in 1996 to talk to a group of Vietnam vets. Defonseca, who told of killing a Nazi soldier, connected with the inmate over the trauma of having committed violence in wartime. She began to visit him as often as once a week. They sent hundreds of letters back and forth, and Labriola wrote her poetry. “Joe is one of the rare people to whom I would trust my very life,” she wrote in the foreword to Prisms of War, a collection of his prison poetry. “We both saw in each other not only the physical wounds, but also more importantly, the invisible and terrible wounds that were much later termed to be Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.”

Defonseca told Labriola she had lost her home in Millis, and that she and Maurice were in difficult straits. Between May 2001 and June 2002, Labriola sent Defonseca five checks totaling $3,000 as a gift, of which she repaid part.

The Defonsecas were still staying with the Schulmans on April 17, 2002, when the judge in the case tripled the award, giving $22.5 million to Defonseca and $9.9 million to Lee. “Mt. Ivy and Daniel’s business dealings with Defonseca and Lee were clearly outside the penumbra of any established concept of fairness,” the judge, Elizabeth Fahey, wrote in her finding of fact. Obviously moved by Defonseca’s story and ruling accordingly, Fahey nevertheless wondered about the Defonsecas’ continued money trouble. Despite all they suggested, “the Defonsecas’ three bank accounts reveal[ed] deposits between December 1996 and February 2000 of over $243,700,” she wrote. “The evidence never made clear how, notwithstanding that amount of deposits, the Defonsecas were claiming financial hardship.” Indeed, the Defonsecas’ bankruptcy proceedings were never completed, and the Defonsecas were ultimately able to sell their home in June 2001.

Karen Schulman did not know about the Defonsecas’ deposits, and the judge’s ruling was quickly appealed by Jane Daniel, freezing the award once more. Schulman had given the Defonsecas her word that they could stay in her house as long as they needed, and she intended to honor that promise. “You have to understand,” Schulman says. “She said to me, ‘Hitler took my family. I have no family members. My animals are my family.'” But the Defonsecas’ presence became a source of tension with Schulman’s daughter, Joelle Fantini, who had lost her apartment and needed a place to stay, and thought the Defonsecas were taking advantage of her mother. “They would always speak French at the dinner table to each other,” Fantini says. “That was a red flag.” Despite the couple’s continued reliance on charitable assistance, by the fall of 2003, Schulman and her daughter say, Misha Defonseca was buying large amounts of pet food and receiving packages by mail order. “She always showered my husband, my son, my parents, myself with gifts,” says Fantini. The Defonsecas also showed up in new cars: Misha a blue Mazda sedan, Maurice a red Honda Element. The Schulmans asked the Defonsecas to move out, and in the end had to consult a lawyer, who sent a notice to quit the premises. In November 2003, almost two and a half years after they moved in, the Defonsecas bought a house in Dudley, near the Connecticut border, for $190,000. They did not need a mortgage.

On May 17, 2005, an appeals court upheld the judgment against Daniel. Lacking the tens of millions she’d need to comply with the ruling, she negotiated settlements with Defonseca and Lee. She paid Defonseca $425,000 that she was to inherit from her father, and, after spending a night in the Framingham jail in May 2006 for falling behind on her payments to Lee, agreed to let Lee’s lawyer sell her historic home in Gloucester, which she’d bought in 1998 and operated as a bed and breakfast.

It was only then that Daniel began probing whether Defonseca was really a Holocaust survivor. Before the first trial, in 2001, she’d told me, “It’s not our job to decide for the world what is or isn’t true.” But her sleuthing in 2006 uncovered financial documents in the court records for Monique Ernestine Defonseca, with the birth date May 12, 1937. (This would make Defonseca four at the beginning of her ordeal; in Misha, she claims she was seven.) Daniel tried working with private investigators, but they made little headway. Then, in August 2007, she launched a blog with the hopeful title Bestseller! It would be “a real book being written in real time,” she wrote in the first post, which also included a book jacket design (the word “Bestseller!” in screaming red type, a courthouse, a statue of blind justice) as well as her e-mail address and phone number. “I especially hope to hear from those of you who may have been there at the time, or who knew the people I am writing about.”

In December 2007, Daniel heard from Sharon Sergeant, a Waltham-based genealogist. Sergeant had worked as a consultant at Honeywell Bull when Maurice had been an executive there, but they had never met. She stumbled onto Bestseller! through a link on the blog of an attorney she knows. “I said, ‘Oh my God, this is crazy,'” Sergeant says. As she kept reading, she became convinced that the mystery behind Defonseca’s identity could be resolved. “I said, ‘There has to be a way,’ especially because I knew more and more records were coming out”—archives being opened to the public, or made available in digital form.

“I contacted Jane, and I said, ‘I think this case can be solved.’ And she said, ‘Really?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, it’s not going to be easy, because everybody likes this story. There are all these emotional issues.'” Before getting involved, Sergeant did some research on Daniel. She also talked over the project with a friend who is a child survivor of the Holocaust, who reminded her that Daniel “has 33 million reasons why she wants this to be a fraud.” But in the end, Sergeant took on the Misha project, doing the work pro bono. For years, Daniel had been cast as Defonseca’s tormentor, but Sergeant saw Daniel as the damsel in distress. “Jane doesn’t have any money. She’s also in a crisis situation, because of the judgment. The last plug is going to be pulled momentarily: the house, the contents, her livelihood.”

Genealogy has an image as a fuzzy pursuit for hobbyists who poke around dusty church basements and hunch over microfilm machines in search of their seventh cousin three times removed. But Sergeant approaches the discipline with as much rigor as she did her earlier work at Honeywell Bull. “If it’s a big complex project, I like it,” says Sergeant. Tapping into her network of contacts, she found forensic genealogists who offered to analyze known photographs of Defonseca, and an amateur genealogist in Belgium, herself a hidden child, to dig through local phone books and deportation lists and archives. Sergeant and her team looked for information about the family reputed to have hidden Misha and about Monique De Wael, the identity that Defonseca says was imposed upon her after the war. Sergeant’s Belgian contact turned up a baptismal certificate for Monique De Wael. It, too, carried the birth date May 12, 1937, further proof that Misha had been four and not seven when she began her journey across Europe. The Belgian contact also found a roster that placed Monique in elementary school in the fall of 1943, when Defonseca claimed to be living with a wolf pack in Ukraine. Daniel posted these documents on her blog this past February.

By then, Sergeant and her team weren’t the only doubters pursuing Defonseca. The movie Survivre avec les loups, by the French Jewish filmmaker Véra Belmont, opened in France and Belgium in mid-January, putting Defonseca in the spotlight as never before. Enraged by the film, Serge Aroles, the author of a skeptical volume about feral children, flagged inaccuracies in Defonseca’s descriptions of animal behavior and wartime history. Aroles contacted Maxime Steinberg, the leading historian of the Holocaust in Belgium, who spoke out against Defonseca’s memoir on national television on February 20; Daniel’s blog could be seen on a computer screen in the background. Then Marc Metdepenningen of the Brussels newspaper Le Soir reported that Monique De Wael’s parents, Robert and Joséphine, had been members of the Belgian resistance and died in Nazi custody.

For two decades, Defonseca had insisted that she was Misha, the girl who survived with wolves. On February 22, she told a reporter for Le Soir that she was “extremely wounded” by all the accusations made against her. A week later, Le Soir presented Defonseca with a dossier of information, including statements from a De Wael relative who knew the real story, prompting Defonseca to release a confession through a Brussels lawyer. Monique’s mother, Joséphine De Wael, died a loyal member of the resistance, but Robert, Monique’s father, had betrayed his fellow resistance fighters, giving their names to the Nazis. Monique was raised by her grandfather, Ernest De Wael. When she was 15, she appealed to a Belgian commission to declare her father a political prisoner, making her eligible for state benefits. But with her father deemed a traitor, her appeal was denied.

“Yes, my name is Monique De Wael, but I’ve wanted to forget that since I was four years old,” Defonseca said in her statement. The story of Misha, she went on, “is not actual reality, but it was my reality, my way of surviving…. I ask forgiveness of all those who feel betrayed, but I beg them to put themselves in the place of a four-year-old girl who had lost everything, who had to survive, who fell into an abyss of solitude, and to understand that I never wanted anything other than to ease my suffering.”

In July, the French magazine XXI reported that Defonseca is working with her French publisher on a new book, drawing on her father’s papers and material from the Belgian archives and recasting herself as a different sort of victim. She still has supporters in Millis. Valerie Sullivan, the daughter of Defonseca’s friend Odette, continues to take Defonseca at her word. She says she spoke with Defonseca after her public admission, and that “she was essentially forced to say this is a hoax, but that’s not how it is. I’ve never known her to lie to us.”

But others feel betrayed. “Where was she at, that she had to do this to so many people?” says Joni Soffron of Wolf Hollow, who a few months earlier had been promised a trip to Paris to join Defonseca at the movie premiere. “I hoped because of our friendship, she would reach out to me,” Soffron says, but she never heard back. Karen Schulman, who put up the Defonsecas for two and a half years, says, “I will check on everything for the rest of my life before I ever believe a story firsthand.” Joe Labriola, her imprisoned former friend, adds, “In 35 years of prison, nobody has conned me. She was that good. I have to applaud her.”

Jane Daniel says she suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of her dealings with Defonseca. “I had 70 percent of the symptoms,” she says. “Going through the legal system is like having cancer. It’s the first thing you think about in the morning, and the last thing you think about at night. It is trauma.” Nonetheless, that hasn’t prevented her from heading back to court: In April her lawyer filed a complaint charging Defonseca with perpetrating a fraud on the court. Daniel has been had, and yet one wonders how much of this sh

e brought upon herself. Had she not pursued Defonseca, had she paid closer attention to the Holocaust scholars who warned her the book wasn’t a true story, she would have been spared the destructive legal fight. I asked her whether she thought it a mistake to publish Misha in the first place. “I think I made a rational choice based on the information I had at the time. I don’t think it was a careless choice.” Once she began turning up documents about Monique De Wael for her blog, Daniel stopped posting new chapters of Bestseller!

But she did keep writing. “I had lost everything. The only thing I had left, in terms of assets, was this story,” she says. She is publishing Bestseller! herself, available this month. And she says she still has the phone number of the Oprah producer who set up the Wolf Hollow shoot.