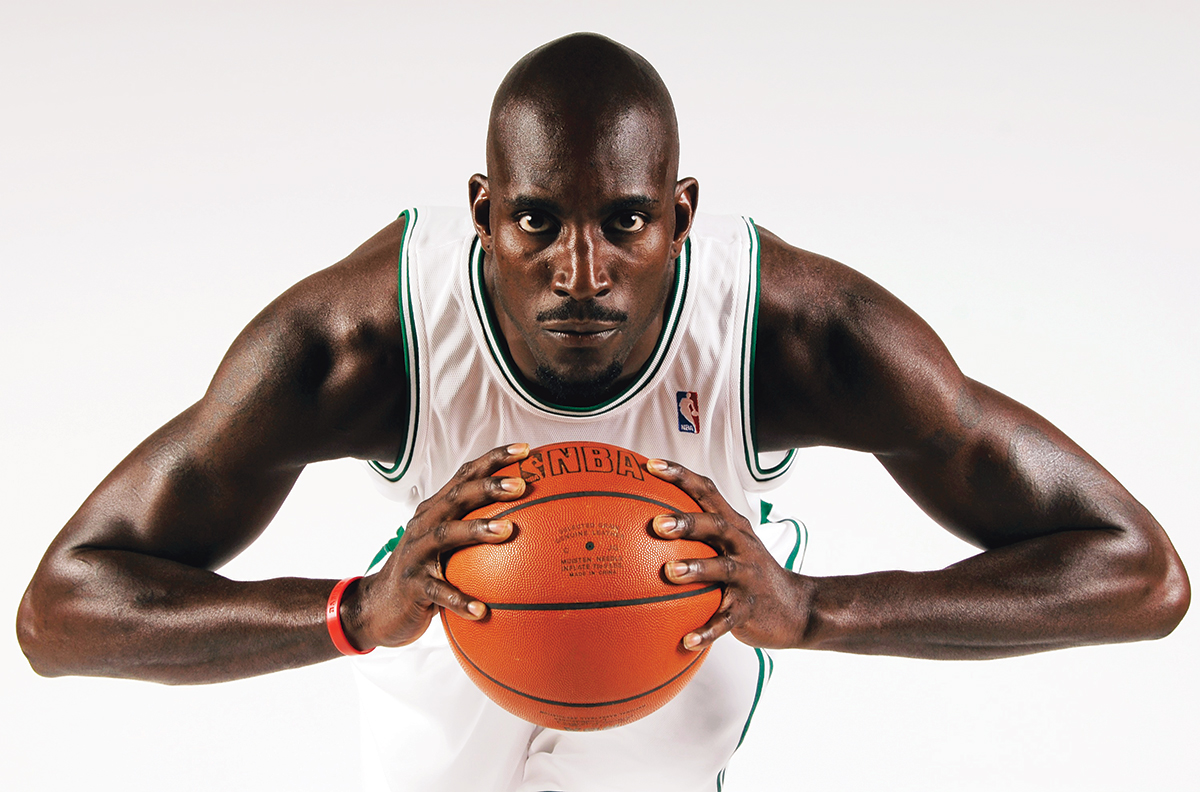

Kevin Garnett, By the Numbers

Getty Images

IT WAS THE FREE THROWS THAT HAUNTED HIM. Kevin Garnett had played horribly in one of the biggest games of his life — Game 5 of the 2008 NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers — a “garbage” performance by his own admission, punctuated by two missed free throws that could have tied the game with 2:31 to go. After enduring a five-hour ground delay at Los Angeles International Airport the next day, the team finally arrived back in Boston a little before 11 p.m. “I was pissed,” Garnett says. “I missed those fucking free throws. That bothered me the whole trip.” When the plane touched down at Logan, Garnett called a car service to take his family home. Then he headed to the Celtics’ practice facility in Waltham.

An empty basketball court had always been Garnett’s refuge from the critics who said his style of play — selfless to the point of being deferential — wasn’t conducive to winning a championship. He had seemed strangely passive in the first four games of the series, and he’d given naysayers more fodder in Game 5 (one basketball writer opined that Garnett was a “fake franchise player,” and another compared his record of postseason futility with that of Yankee Alex Rodriguez). Alone in the Waltham gym, he drained foul shot after foul shot.

By the time he finally went home, it was the morning of Game 6.

That night, before tip-off, Celtics coach Doc Rivers was concerned enough about Garnett to send assistant coach Kevin Eastman to check on him. Eastman, seeing the familiar death stare that is part warning to reporters (who by now do not need it), part meditation, reported back: “I think he’s good to go.”

And indeed he was. Late in the first quarter, with the Celtics trailing 10-8, Paul Pierce grabbed a rebound and pushed the ball up the floor. Garnett beat his defender, Laker power forward Pau Gasol, down the court and got into position under the basket. Garnett shucked Gasol to the ground, and Pierce delivered the pass from the top of the key for an easy lay-up. It was at once a subtle yet assertive move, and Garnett’s teammates understood the significance immediately. “Our whole bench just exploded because we knew it was over,” Rivers says. “On that play.”

By the fourth quarter it was no longer a basketball game. It was Carnival on Causeway Street. The new Garden had become the old, cigar smoke filling the air. When the final buzzer sounded, Garnett had scored 26 points and grabbed 14 rebounds in a decisive 131-92 win. Though he rarely responds to his doubters, during a postgame interview with Michele Tafoya of ABC he couldn’t resist yelling into the television camera, “WHAT ARE Y’ALL GONNA SAY NOW?”

It is a popular belief that Garnett secured his legend the day the Celtics capped their unprecedented one-season turnaround by winning the championship, a championship he and the team will defend beginning this month. But that’s too easy. Garnett is a unique, even revolutionary, figure — the first high school player to go pro in 20 years, and three years later the owner of a massive contract that shook the NBA — yet he has a game as old-school as Bill Russell’s. More than any other NBA star, Garnett has also been sold short by the narrow way greatness is defined for professional basketball players. Nothing about him changed in the 24 hours after his late-night penance in the empty practice gym — it’s just that to appreciate the player he has always been requires an entirely new way of looking at him, and his whole sport.

IN JULY 2007, KEVIN GARNETT WAS PONDERING HIS FUTURE at his Malibu home with his friend, Tyronn Lue, a guard currently with the Milwaukee Bucks. The Celtics had just traded for Ray Allen, a veteran All-Star from Seattle, and now were pushing hard for a deal with the Minnesota Timberwolves to land Garnett. “He was like, ‘Man, it’s cold in Boston,'” Lue says. “I said, ‘Shit, it’s cold in Minnesota.'” Later Garnett had a similar conversation with another friend, Detroit’s Chauncey Billups, who told him the same thing: If he wanted to win a championship, he needed to go to the Celtics.

Two months earlier, Garnett never would have even considered Boston. The Celtics had been bad the previous season, 24-58 bad, but they had hope in the form of the upcoming draft, where two potential franchise players — Greg Oden and Kevin Durant — were waiting. Their plans were tied to the draft lottery, held a month before the actual draft, during which numbers are drawn to determine the order of the first 14 picks. Thanks to their terrible record, the Celtics had the second-best chance of winning the top draft pick. They got the fifth.

That disappointment gave way to a bold new strategy. The team would scrap the youth movement that had been under way since the 2005 season and try to pull off not one, but two blockbuster trades. They made the first, for Allen, on the day of the draft. For the second, the Celtics pursued a number of big-name players including Jason Kidd, Shawn Marion, and Gasol, then of Memphis. But all along they were really focused on Garnett. “We had plans A, B, C, and D,” says Steve Pagliuca, the team’s general partner. “But getting KG was plan A-plus.”

The Celtics were taking a big risk, both financially and on the court. To add Garnett and Allen, they had to trade away almost half their roster and take on more than $130 million in contracts for two players in their thirties, i.e., past their prime. Garnett’s and Allen’s salaries just for last season, combined with Pierce’s, totaled $56 million, pushing the Celtics over the salary cap. To complete the roster with veteran free agents, the Celtics had to go into the luxury tax bracket, which demands a dollar-for-dollar penalty. With a final payroll of over $76 million, the Celtics were paying an extra $8.2 million in those luxury taxes, which even in the NBA isn’t chump change.

And then, of course, there was no guarantee that having three stars on the same roster would actually work. NBA history is filled with attempts to create superteams, almost all of which have crashed and burned in a dysfunctional mess of conflicting egos and agendas. The most recent example came in 2004, when the Lakers added Gary Payton and Karl Malone to a lineup that already had Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant. The Hall of Fame foursome were good enough to get to the NBA Finals — whereupon they self-destructed against Billups’s Pistons, Payton bitching about his playing time and Shaq and Kobe bitching about each other.

Accordingly, from the beginning, there were doubts in Boston. Two days after the trade, the Globe‘s Bob Ryan wrote, “That’s it? Someone actually thinks this Celtics team will win the East and contend for the championship? Really?” (In fairness, this was before the team had signed James Posey, who would prove to be a critical role player — but then, no one was planning a parade route after he signed, either.)

The skepticism began with how the three stars would play together — would Allen’s surgically repaired ankles hold up, would Pierce sulk if he didn’t get the attention, or the last shot — but the biggest questions were reserved for Garnett. Could he, in the hoariest sportswriter-speak, finally “will his team to victory”? The answers, of course, came in the form of banner number 17. Though as Garnett uniq

uely demonstrates, just framing the question that way badly misses the point.

NBA superstars are traditionally judged by two criteria, scoring and championships, and the perception is that one feeds directly into the other. Blame it on Michael Jordan. In our mind’s eye we will always see Jordan with the ball in his hands at the end of the game — he knows he’s taking the shot, his defender knows it, everyone in the freakin’ arena knows it, and we all know it’s going in. That’s greatness defined in the NBA. It’s also “not Garnett’s game,” notes Britt Robson, a Minnesota journalist and longtime Garnett observer. “Some people resent that. They see it as cowardice. They won’t say it that straight, but that’s what they’re implying.”

Garnett stands nearly 7 feet tall (he swears that he is 6 foot 11¾), meaning that by all rights he should play center. But he has always steadfastly rejected that categorization. Think about the game’s great centers and you think of their go-to moves: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s skyhook, Hakeem Olajuwon’s “Dream Shake.” Garnett’s moves, by contrast, have no name. His repertoire, heavy on 20-foot jump shots and turnaround fadeaways, is more usual for a guard than a big man. It’s also uncannily effective.

Garnett takes about 16 shots per game (Kobe Bryant, the league leader in attempts the past three years, has averaged as many as 27), and he hits 49 percent of them. That makes him a very good scorer, though not one of the league’s best: In his 13 years in the NBA he has finished in the top 10 in points per game just three times. (“To be a great offensive player, you have to be single-minded,” Rivers says. “It has to fuel you. But that doesn’t fuel Kevin.”) But while those numbers tell us something, they also lead to more questions. On the one hand, Garnett takes a decent number of shots and makes a high percentage; on the other, he doesn’t shoot as much as other superstars — maybe he should shoot more. Or perhaps he has found the right balance. What we need is perspective, and we will use more numbers — much more complex numbers — to get there.

The term “sabermetrics” comes from Red Sox senior adviser Bill James, who started a revolution in baseball when he began to go deep inside the game’s statistics to try to answer similar queries, such as whether it’s more productive to take a walk or swing at a bad pitch and possibly manage a hit. The answer is to take the walk, but that’s another story — actually, a whole book, Michael Lewis’s bestselling Moneyball, which helps account for why sabermetrics’ influence on baseball is well known. But in fact it reaches into all sports, and especially basketball. The seminal volume on the application of Jamesian analysis to basketball stats is Dean Oliver’s Basketball on Paper. Unlike Lewis, Oliver didn’t have a character as colorful as Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane through whom to tell his story, but to his readers it was no less eye-opening.

About a third of NBA teams now employ some kind of numbers guru, and the Celtics have been at the forefront of the movement. When Wyc Grousbeck bought the team in 2002 with his partners, he brought with him an MIT-trained M.B.A. named Darryl Morey. Morey was drawn to how so-called advanced metrics could be applied to roster and on-court strategies, and began to press his theories on Danny Ainge, who runs the team’s basketball operations (and who has “a healthy skepticism” about the new-wave analysis, says Grousbeck). The Celtics have also since brought on a Harvard Law grad named Mike Zarren, who crunches reams of data for the front office and coaches — the specific details of which are zealously guarded by the team. Morey, meanwhile, went on to become the first stats-junkie GM in the NBA when he was hired by the Houston Rockets, which makes him the Theo Epstein of basketball.

The key concept in Basketball on Paper is the use of possessions as a way to understand how games are won and lost. The average NBA team will have the ball between 80 and 90 times per game, and the team that uses those possessions more efficiently will win. It’s a relatively simple idea, taking a seemingly fluid sport and breaking it down into units that can be recorded as neatly as baseball innings.

From there, things get more complicated. Once you have logged a team’s possessions, you can track individual players’ contributions in the form of their offensive rating (how many points a player scores per 100 possessions), defensive rating (points allowed per 100 possessions), and usage percentage, which estimates how often a player is involved in his team’s offense. Which at last brings us back to Garnett, whose career usage percentage is 25.6 percent. By way of context, that’s lower than that of Ray Allen and Paul Pierce, and far lower than that of Allen Iverson, LeBron James, and Kobe Bryant, who are all above 30 percent.

And that’s one of the big things that throw people about Garnett, says ESPN’s John Hollinger, one of the pied pipers of the statistical movement. “Our perception of a dominant player is that he has the ball in his hands all the time. Whether it’s good things or bad things, he’s doing things. The perception is that Garnett disappears.”

But of course that’s not true. In the 2006 book The Wages of Wins, an economics professor named David Berri laid out another new-wave stat, “wins produced,” which crunches standard box-score stats to assign credit to individual players for their team’s success. And according to Berri’s numbers, the best player in the NBA from 2002 to 2006 was not Bryant, who was consistently among the league’s leading scorers during those seasons, or Tim Duncan, who won two of his four championships during that period. It was Kevin Garnett.

In Minnesota, where he played alongside only three fellow All-Stars during his dozen years, Garnett’s skills were enough to produce 50-win seasons, but rarely enough to get out of the first round of the playoffs. In 2004, after the Timberwolves brought in stars Latrell Sprewell and Sam Cassell, the team had its best season ever, advancing to the Western Conference Finals. Garnett was named league MVP — an honor backed up by all the cutting-edge quantitative analysis. In 2005, Garnett put in a similar statistical performance, and again the metrics ranked him as the game’s best player. But Minnesota failed to make the playoffs, and Garnett finished 11th in the MVP voting, without a single first-place vote.

“People looked at Garnett [in Minnesota] and say he’s got all these numbers, but he doesn’t appear to make his team better,” Berri says. “Maybe they just weren’t that good.”

Let’s flash back to Garnett’s signature 20-foot jump shot. According to Hollinger, Garnett took more perimeter jump shots last year than at any other time in his career. This, in so many words, made a lot of Celtics fans pull their hair out. The guy’s 7 feet tall (okay, 6 foot 11¾). Why doesn’t he just get into the paint, where he belongs!

In fact, by playing outside, Garnett drew attention away from the basket, which for the Celtics meant that Pierce and Rajon Rondo were freed up to attack the rim. It also allowed center Kendrick Perkins to occupy the lane, which left him open for dunks and lay-ups when his defender would inevitably leave him to help cover a slashing Rondo or Pierce. (Perkins made 61 percent of his shots last season.) Garnett is also a deft passer from the high post, and frequently connected with Allen when he came off screens for open three-pointers. Every member of last season’s starting five had higher offensive ratings than their career averages, and all but Allen had higher shooting percentages (and he was just 1/100th off his career mark). No one benefited more than Pierce. The Celtics captain set a career high in offensive rating while posting the lowest usage percentage since his second season in the NBA. Put simply, Pierce had less to do, and that meant he did everything better.

The offensive system Garnett enabled the Celtics to run had two primary benefits: It kept players happy, since it got everyone involved, and it made it possible for the team to focus its energies on defense. By the traditional measure — points allowed — the Celtics played the second-best defense in the league last year. But it was even better than that. Hollinger determined that their team defensive rating was almost eight points better than the league average, ranking them the third-best defense in the NBA since the modern box score was implemented in 1974. More impressive, they became a great defensive team after being among the league’s worst the previous season. “To put everything together and do it in one year is really amazing,” says Kevin Pelton, a writer for the website Basketball Prospectus. Pelton’s stats show that the Celtics were the best in the league at defending shooters (the official term, for those taking notes, is “effective field goal percentage defense”) and forcing turnovers. They played solid straight-up defense and still were able to gamble for steals. According to Pelton, no team has ever led the league in both categories.

The architect of the Celtics team defense is associate coach Tom Thibodeau, another new addition last season. The scheme relies on constant communication and aggressively switching assignments. In Garnett — who never stops talking, and can shut down any player — he had the ultimate individual weapon to build around. “Kevin sold our team defense,” Rivers says. “We give a lot of credit to the coaches, but let’s be honest: Without Kevin, it doesn’t work.”

Garnett was the landslide winner for Defensive Player of the Year, an honor he curiously had never won before. The award was clinched by performances like the one he put in during a game in January, when he found himself matched up with Houston Rocket behemoth Yao Ming, who stands a half-foot taller and outweighs Garnett by 60 pounds. Garnett does not typically guard men of this size, but Perkins and Scot Pollard had both fouled out, and so with just over six minutes left and the Celtics leading by one, he went to work.

Individual defense in the NBA is really about geometry. Yao had been getting the ball about 4 feet from the basket and dropping in bank shots all night. Garnett’s job was to change Yao’s angle, which he accomplished by pushing him away from his preferred spot before the entry pass arrived. Now 6 feet away from the basket, Yao missed a hook shot. A few possessions later, he had become visibly uncomfortable. He tried an assortment of fakes and pivots, but Garnett held his ground, then swatted away Yao’s awkward-looking shot, punctuating the block with a primal scream. With the victory secure, Garnett emerged from a time-out raising his arms slowly skyward, demanding the spotlight, building the crowd into a frenzy.

IF HE HAD WANTED, GARNETT COULD HAVE BASKED IN MOMENTS like that all season. After all, he had waited his entire career to be in this position. But he understood the delicate balance of egos that had been struck by bringing him in, and — his awesomely unhinged look-at-me freak-outs aside — he remained almost Zenlike in his devotion to team. And there you have the truth beneath the final misjudgment of Garnett: His pro wrestling theatrics, the beating on the chest and the streams of profanity — it’s no act. “This is who this guy is, 24/7,” says venerable play-by-play man Mike Gorman, who has been around the team since 1980. “I thought no one could be that intense. I was wrong.”

There are three places where the members of a professional basketball team interact. The most obvious is in games, which naturally receive the most scrutiny. The second is in the locker room, and an anthropologist could have a field day studying the complex interpersonal relationships among players, and between players and the press. The third place is behind closed doors, in practice and in meetings, and it is by far the most critical. You can fool the fans and the press, but you can’t get anything past NBA players, who are among the world’s foremost cynics. “Kevin is all by example,” Rivers says. “You can talk about it all day, but if you don’t back it up, no one’s going to listen to you, and you will get old real quick.”

That started during Garnett’s introductory press conference, when he refused to have his picture taken without Pierce and Allen in the shot. From that point on, he always waved off questions that even hinted at personal acclaim. After a much-hyped victory over the Phoenix Suns in late March, Pierce gave an emphatic summation of Garnett’s impact on the franchise, saying, “He changed the culture around here.” Garnett, seated next to Pierce, responded by putting his hand over Pierce’s mouth. “We changed it. We.”

It continued during the season, as Rivers had to invent ways to shorten practices to prevent Garnett from burning himself out, and in film study, where Garnett immediately owned up to his mistakes — out loud, in front of his teammates. He did it so readily, the coach was taken aback. “In my experience, the star player a lot of times wants to explain their way out of it,” Rivers says. “He would look at the tape and say, ‘God, I was awful.’ That’s leadership.”

One day last September, a month before training camp officially opened and a half-hour before an optional practice was scheduled to begin, Garnett was already on the court, working on his shot. After missing three straight, he ran six baseline suicides — two for every miss. This was why the Celtics had blown up their team, and blown the salary cap, but it would be months before their big gamble would be validated. Taking in the scene from above the floor where the Celtics offices are located, Wyc Grousbeck was feeling confident. Turning to friends, he said, “That’s who Kevin Garnett is.”