Making Pictures

Photograph by John Goodman

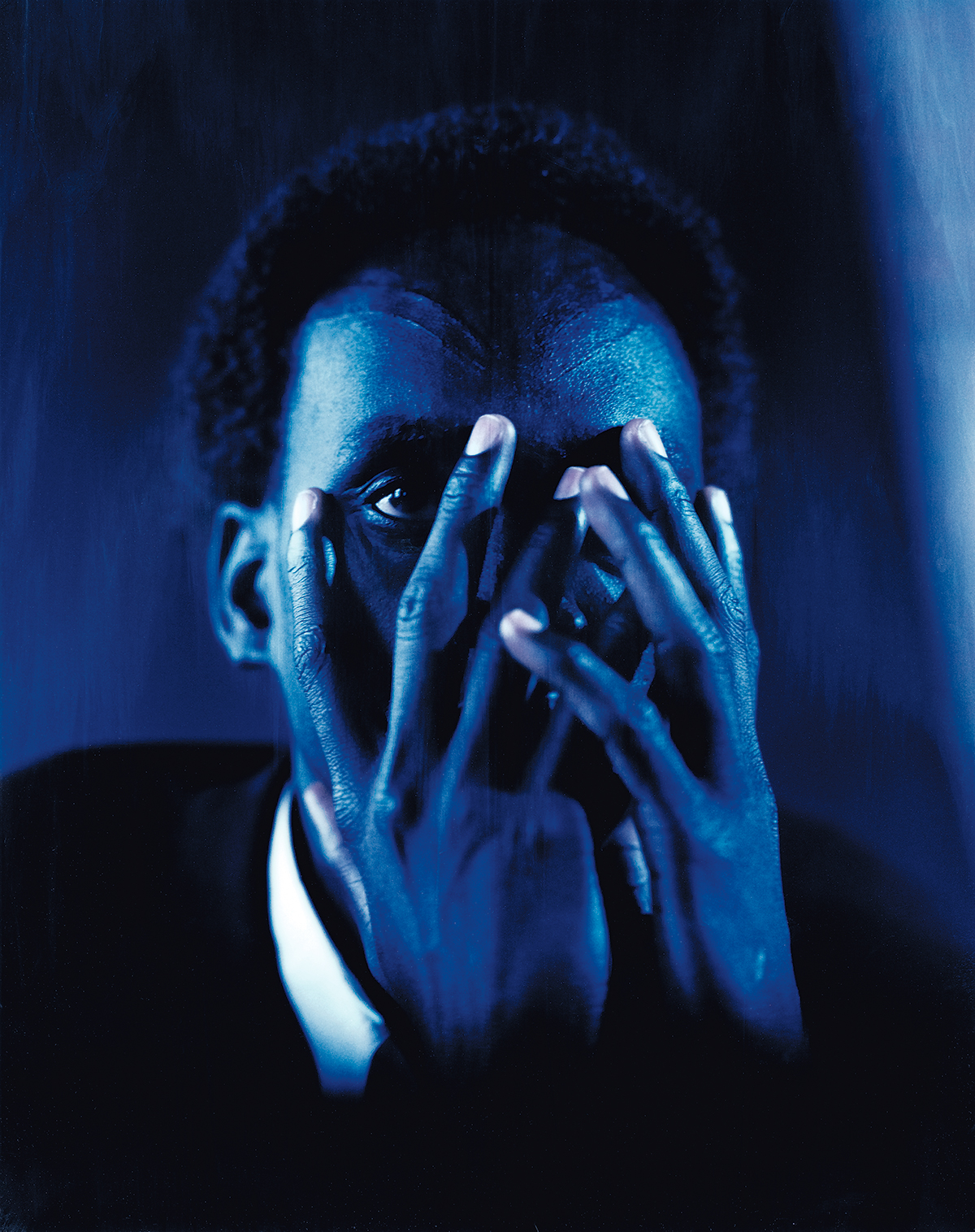

I am standing with John Goodman in his Fort Point studio in almost the exact spot where he photographed abolitionist Francis Bok five years ago, the light spilling in then, as it does today, from 10-foot windows that look east down Summer Street. Bok had written a book about his escape from slavery in Sudan; the publisher, St. Martin’s Press, hired Goodman to do the portrait. “It has a certain feeling about imprisonment, and about horror,” Goodman says of the photo, then stops himself—he wants his pictures to spark the imagination, and believes too much information can spoil that. “There are some things I want to leave to the viewer.”

Good thing, then, that Goodman’s portfolio speaks so well for itself: Over the course of a three-decade-plus career, the Newton native has shot for numerous national magazines and fashion houses, and his photographs can be found in the collections of the MFA, the Met, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, to name a few. But if his success has been remarkable, so, too, is Goodman’s steadfast commitment to his Boston roots. These days the story out of the Fort Point art community is one of real estate, of developers forcing hundreds of painters, sculptors, and photographers from their studios. What gets lost is that there are still world-class talents working there—one of whom also happens to be among this magazine’s longest-standing contributors. In fact, Goodman has been “making pictures,” as he describes it, in this same minimalist corner studio for his entire career. “I feel like I’m a tree that just kind of grew here.”

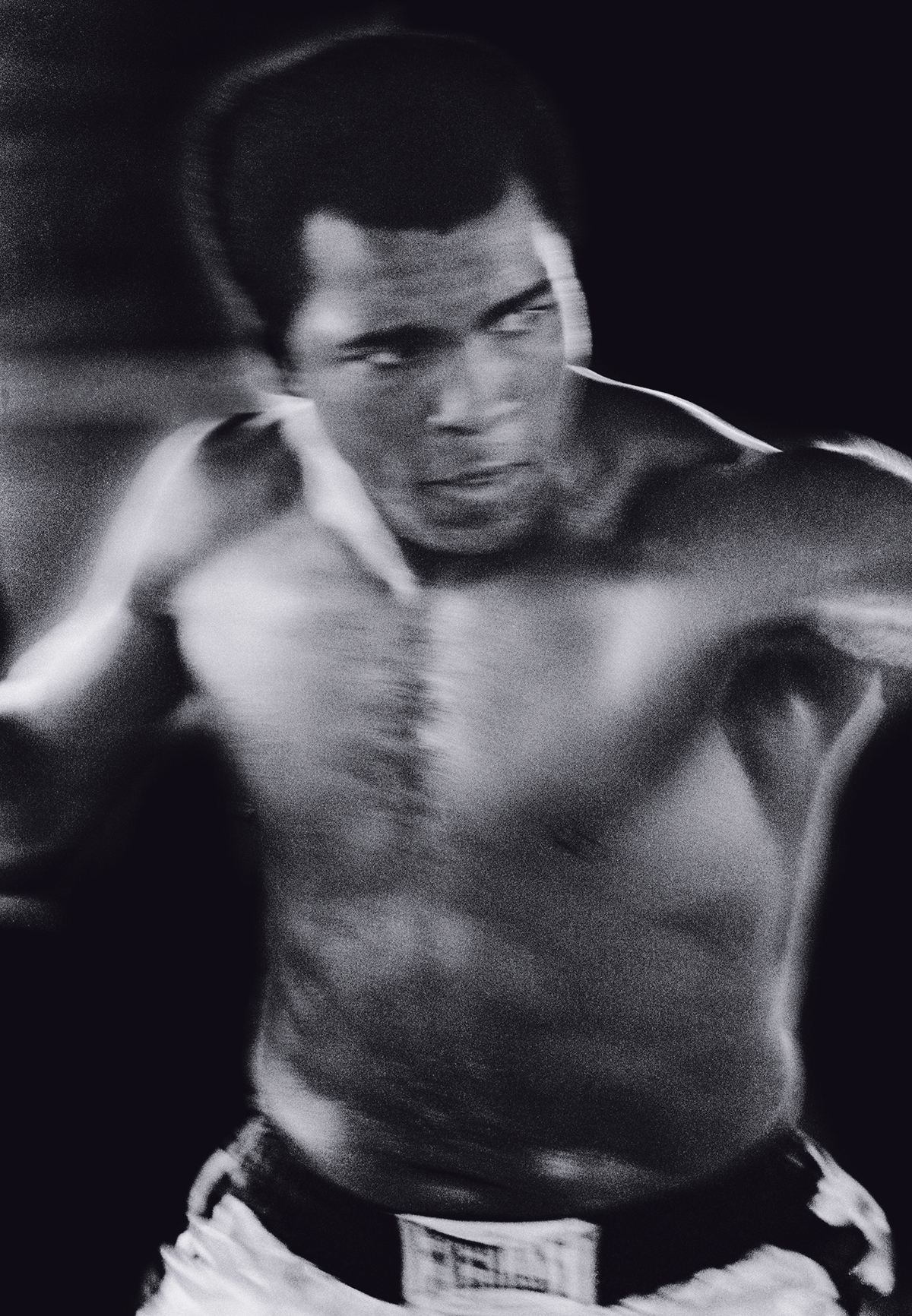

A student of the seminal abstract expressionist Minor White, Goodman initially dabbled in abstraction himself. But he found his stride photographing people, and began his professional career booking editorial gigs for local agencies and publications (including Boston, starting with an image for “Best Water,” of all things, for an early Best of Boston issue). In 1976, local ad man Ray Welch gave Goodman his first big job: shooting Muhammad Ali for a Democratic voter registration poster. When Ali finally entered the ring to pose, he was counting down—”10-9-8-7.…” It took Goodman a moment to realize Ali was giving him just 10 seconds to get the shot. Which he did. Barely. Afterward, the young photographer hung around to watch the champ train, and snapped the picture shown here for his own collection. It would eventually resurface in one of Goodman’s personal projects, a book on the Times Square Gym in New York. “I started shooting it 17 years later, but the way I shot the gym and its inhabitants was just like the way I shot Ali.”

When Goodman’s working, he never knows exactly what he’s going to do. He has ideas, certain parameters, but the final image is often a surprise. “It’s a search,” he says, “and that’s what makes it alive.” Take the portrait of Douglas Adams, irreverent author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, shot in London in 1998 for the business magazine Fast Company, then based in Boston. After taking some pictures in Adams’s office, the duo moved into the streets. When Adams, unscripted, leaned precipitously into a lamppost, Goodman’s lens was there to capture it. “He was playful and willing. When you do a photo shoot, I mean, why not go for it?”

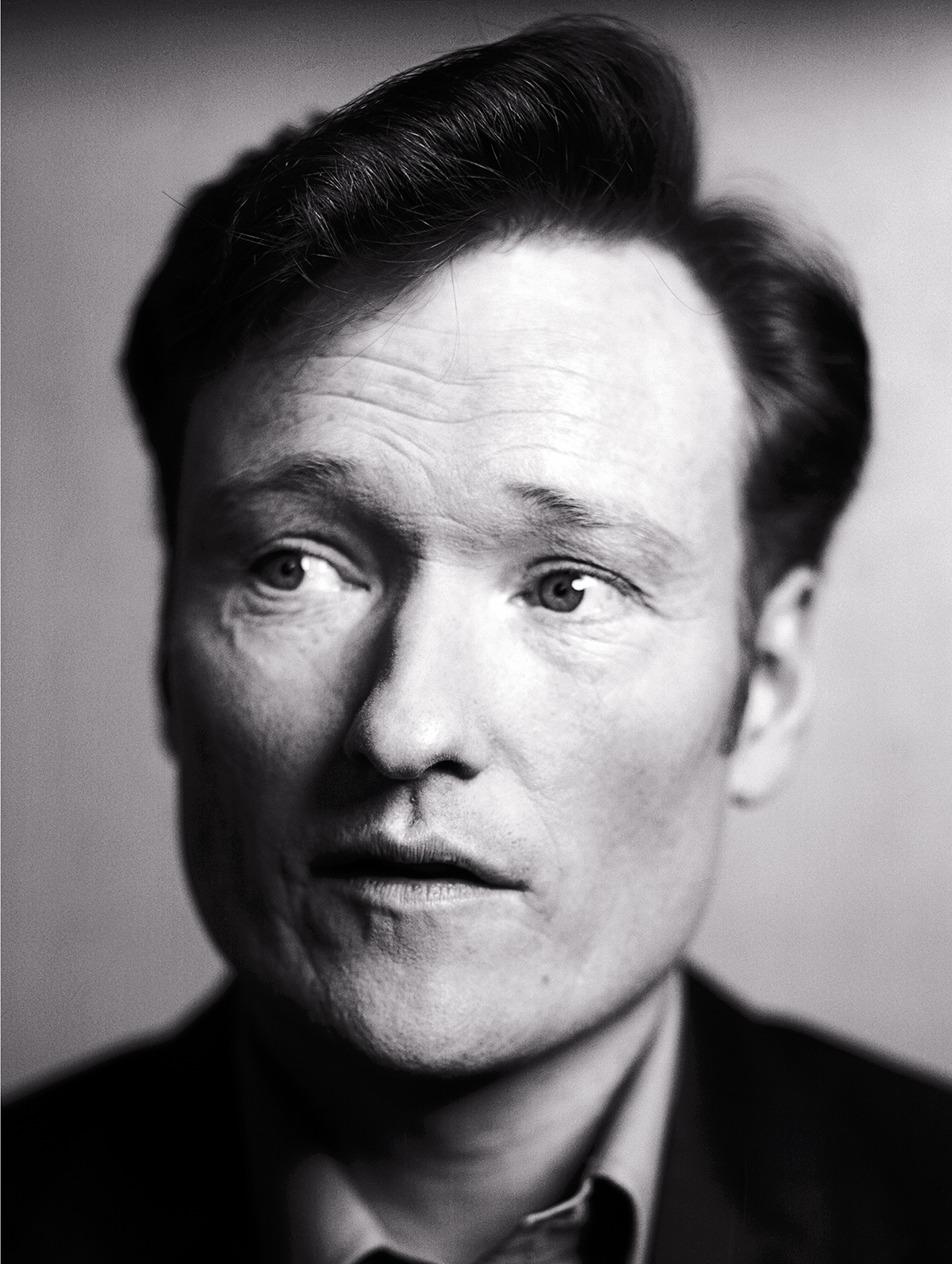

In shooting Conan O’Brien in 2003, Goodman wasn’t interested in portraying the public persona, the things anyone could see. “Conan is certainly ‘up’ and bright, but there’s a very strong seriousness about him, and I wanted to go there.” After the session, he says, O’Brien caught a glimpse of the photo and exclaimed, “You got me, didn’t you?”

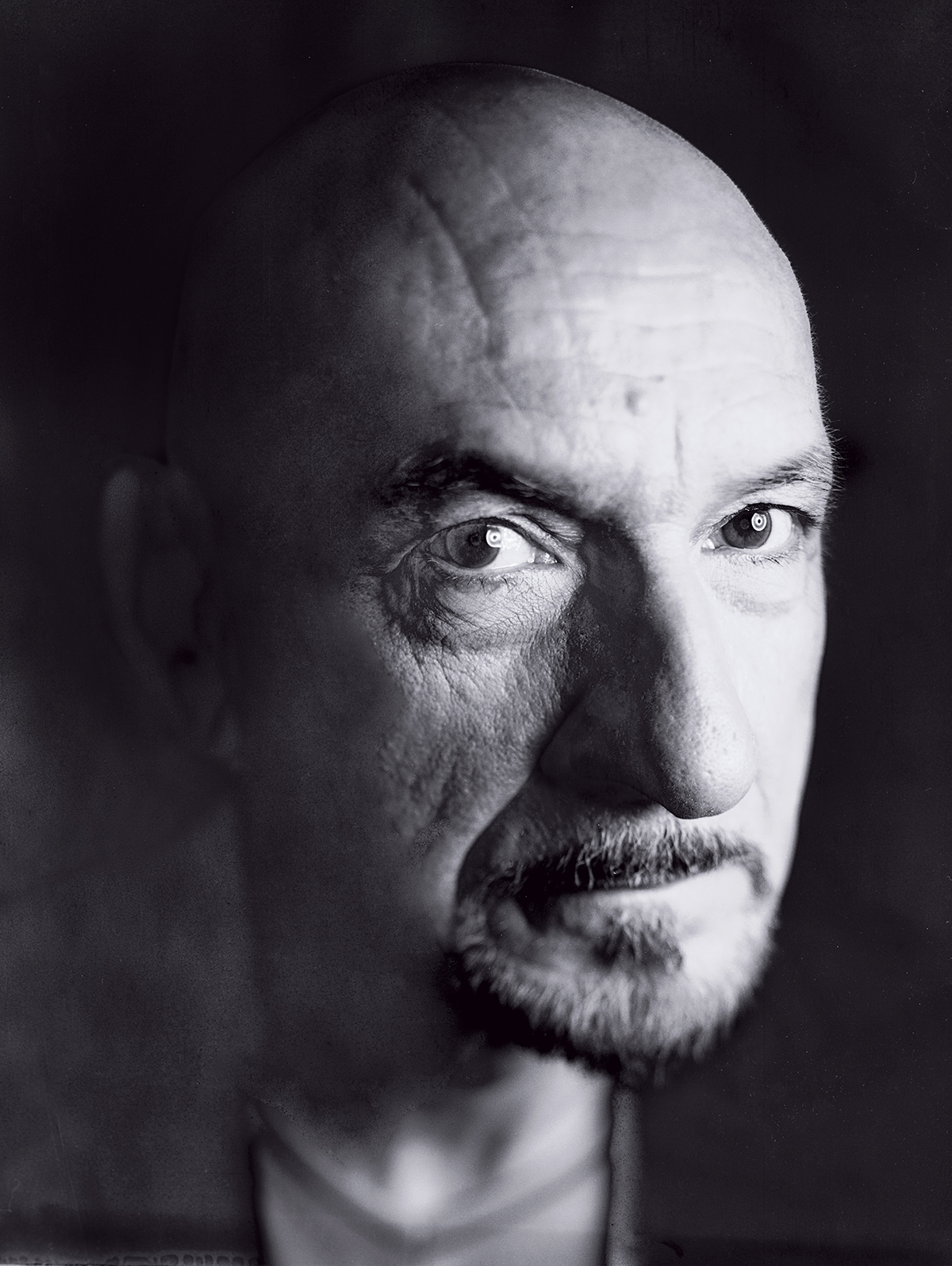

Each time the shutter clicks, Goodman connects more with his subject: “There’s a certain trust that starts to build up, if it’s working.” That came through in his session with Ben Kingsley, an assignment earlier this year for Parade. Goodman spent an hour with the actor in a room at the Ritz-Carlton in Downtown Crossing before he felt comfortable moving in for this close-up, which has never before been published. Kingsley’s peaceful mien deeply impressed the photographer, who felt almost as if he were meeting Gandhi himself. “For days, I was affected by his calmness. I even lost a little of the Boston driver in me!”

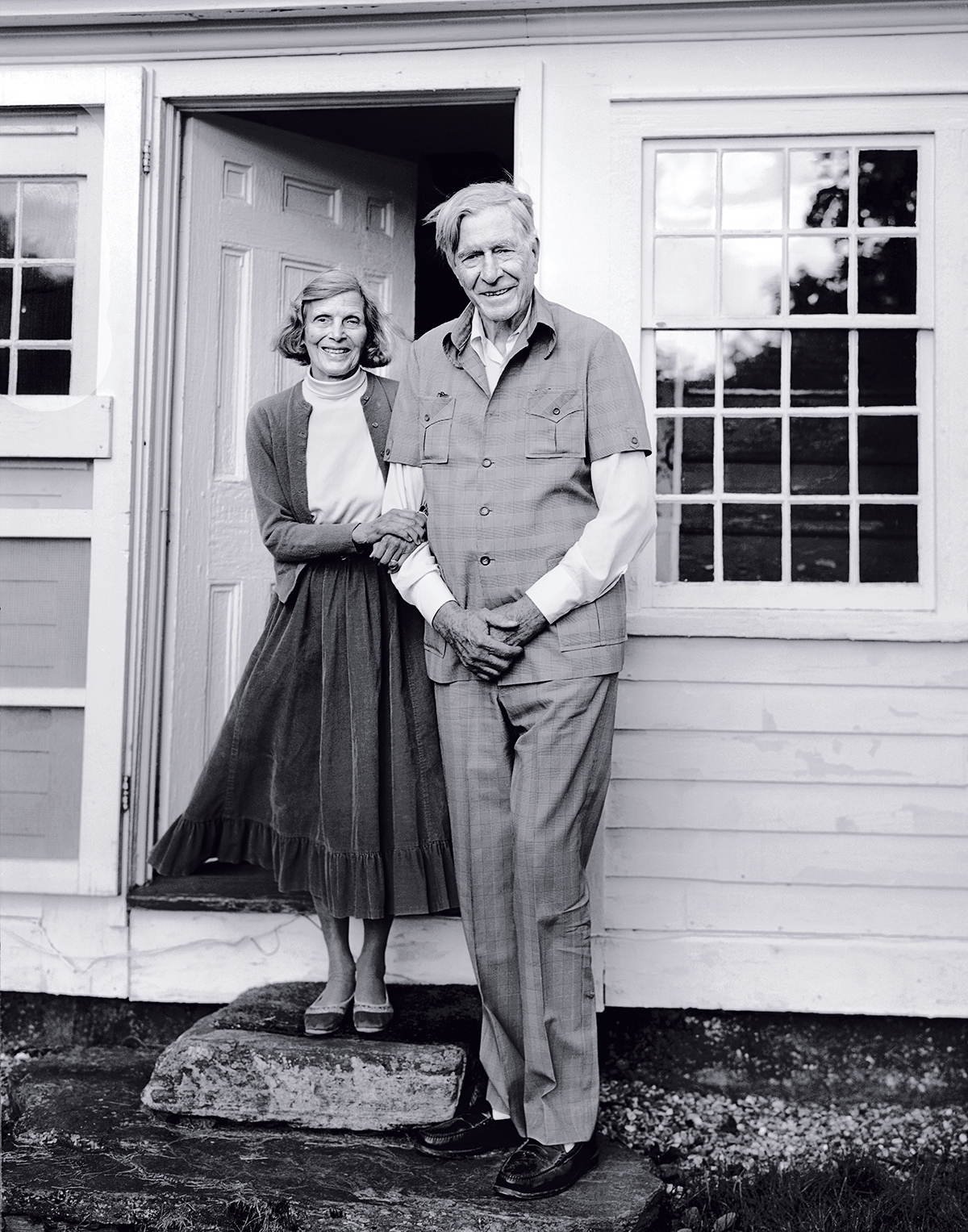

Indeed, Goodman often finds himself changed or moved by those he photographs. Working for Boston in 1994, he met the economist John Kenneth Galbraith and his wife, Catherine, at their Vermont summer home. The session left him with a sense of joy, he says, at the idea of growing old with a kindred spirit. “They were so comfortable with themselves. It was just a beautiful thing to see.”

Even for fashion assignments, a personal connection with the subject helps convey depth—as with the haunting sprite wearing an Issey Miyake gown (the model is a longtime Goodman collaborator), shot for the now-defunct Watertown-based magazine Fine. The results so impressed some Hollywood producers that they plucked a half-dozen images from the shoot to hang in the office of Meryl Streep’s fashion-editor-from-hell in The Devil Wears Prada. Which means, of course, that in that very stylish, very New York–centric film, a crowning bit of chic is owed to one of our own.