He’s Attorney James Sokolove

Sokolove started advertising quietly, placing a small ad deep inside the TV circular of the Boston Globe, alongside listings for The Jeffersons and a new program called Dynasty. The calls that began trickling in were just enough to keep Sokolove afloat. He was able to hire Doug Melzard, an insurance industry vet whom he put in charge of running the office. Melzard’s salary was larger than what Sokolove was drawing, so the newcomer didn’t mind paying for dinner when his boss’s credit card would get declined. After two years, Sokolove knew he needed to reach more people. He needed to be on television.

Sokolove got his hands on the advertisements that firms in other parts of the country had aired, and he studied them closely. “When he first walked into the office, we were shocked,” says John Furst, whose Newbury Street–based Videocraft Productions filmed Sokolove’s first ad in 1981. “He came in with a reel of lawyer commercials. Some of them may have even come from Europe. He was insanely, wonderfully careful to do everything the right way.” Sokolove convened a focus group to review his test spots, to check that they worked as intended. He also hired a respected Suffolk Law professor named Barry Brown, who taught courses on professional responsibility and had previously worked for the Massachusetts Board of Bar Overseers. Brown’s job was to help make sure the ad wouldn’t get Sokolove shut down.

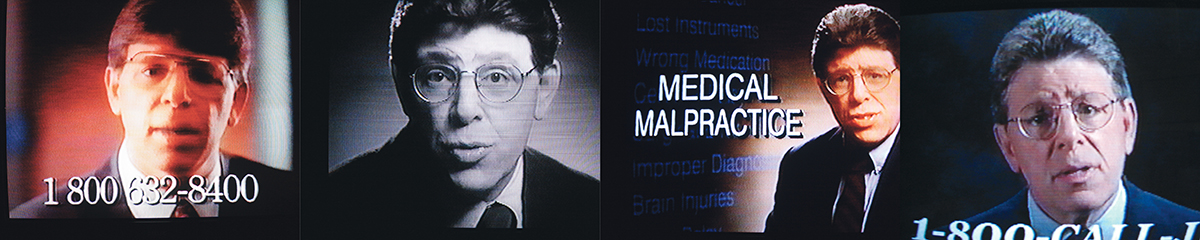

Sokolove in four of the roughly 200 commercials he’s produced over the past 26 years. (photographs courtesy of omega)

Sokolove’s debut ad, which began airing on Boston stations in early 1982, opens with the squeal of brakes and a slow-motion car crash. Because suitable stock footage was not yet widely available, the stunt was staged on a quiet road in Weston. Sokolove had originally hoped the actor Raymond Burr would star, to lend his Perry Mason credibility, but the bar association told Brown that the use of an actor would cross an ethical line. So Sokolove cast himself. At the 11-second mark, he walks onscreen wearing a suit; as he knew from his father, that’s how people expect lawyers to look. Laying down what would become hallmarks of future ad campaigns, he tells viewers they are entitled to money if they’ve been injured and urges them to pick up the phone without delay. “What you need is immediate legal advice,” he says. “If you are injured in an accident, call us immediately.”

Sokolove didn’t keep a television in the office, but his secretary, Florence Nicholson, always knew when the ad ran: The phones would start ringing. Nicholson, Melzard, Sokolove, and his sister-in-law, who also worked for the fledgling venture, would quickly take people’s names and numbers and go on to the next one, returning the calls after the rush subsided.

Through television, Sokolove was able to do what he couldn’t before. If he didn’t share his father’s knack for connecting to clients in their living rooms, a commercial running there could at least simulate the same effect. Better yet, if Sokolove didn’t get it right on the first take, he could try it again and again until he did.

Of course, Sokolove also got the criticism he expected. Early in his first TV campaign, a Globe story quoted some attorneys then considered the deans of personal-injury law in Boston. One of them, a prolific litigator named J. Newton Esdaile, said advertising was “degrading and avoided by better members of the bar.” Esdaile’s rebuke stung. “That guy was the best,” Sokolove remembers. “I thought, Maybe I’m doing something wrong.”

But not so much that he decided to turn back. Within his first couple of years advertising, Sokolove was fielding hundreds of calls a week. “I was like a kid going to a casino—I kept winning,” he says. He soon realized that the work was getting to be more than he could handle. Before long, there was too much work even for the other attorneys he had hired. “When you advertise that you have widgets, you better have widgets to sell,” says Melzard. Sokolove decided he’d start referring the bulk of his cases to other firms, collecting 10 percent of all fees in return. (As a quality-control measure, he would also track every case to make sure clients were well served.)

It was a bold idea at a time when such a business model was allowed in only two other states (Texas and California). Though the arrangement broke with tradition, many affiliates noticed they could get the business boost Sokolove promised, with none of the risk of looking uncouth by advertising themselves. Even as he remained a pariah in some quarters, plenty of lawyers started seeking his help. “These weren’t fly-by-night guys,” Melzard says. “They were big, staid, New England firms who wanted in on what he was doing but didn’t have the balls—pardon my French—to go out and put their faces on television.” Tom Mysliwicz, who led Sokolove’s in-house legal team, then a half-dozen lawyers strong, says Sokolove confounded his critics with the results he was getting. “No one missed the fact that what he was doing worked. They hated him, but they would be happy to be in his affiliate network.”

By 1988 Sokolove and those affiliates were billing $16 million a year, and he was personally pulling down a salary in the high six figures. As Melzard puts it, “He was a marketing guy in a lawyer’s uniform.”

Not long after his ads began turning heads, Sokolove recalls, he got a call from the office of Jim Esdaile, the son and partner of the lawyer who had criticized him in the Globe. Esdaile and a colleague met Sokolove at the Algonquin Club for dinner. While Esdaile now says it was only an informal sit-down, it seemed to Sokolove that they were hoping to do business with him. Sokolove—who smiles as he recounts the story—told the distinguished lawyers that wouldn’t work out.

Sokolove estimates he’s appeared in some 200 different versions of his commercials over the years. A film scholar surveying his body of work might note that the production values have come down since he went to the trouble of staging car crashes. “At some point he decided the time and effort that went into them just wasn’t worth it,” Mysliwicz says. (“Why would I spend $35,000 on an ad,” Sokolove says, “when a $1,500 one works just as well?”)

That realization was a while in coming. In the 1980s Sokolove tried filming intricate testimonials. One such spot featured a young actress in soft focus talking about a doctor’s failure to diagnose her cancer and included a clip of Sokolove inviting viewers to call for an educational pamphlet. Sokolove was pleased with the result. “I was pitching information; it wasn’t about revenge,” he says. Yet the message that seemed to reach viewers was that lawsuits are complicated, and sorting things out can be tricky, and therefore probably not worth the trouble. The people watching him on television, he came to understand, don’t want a discussion. They just want to know what a lawyer can do for them.