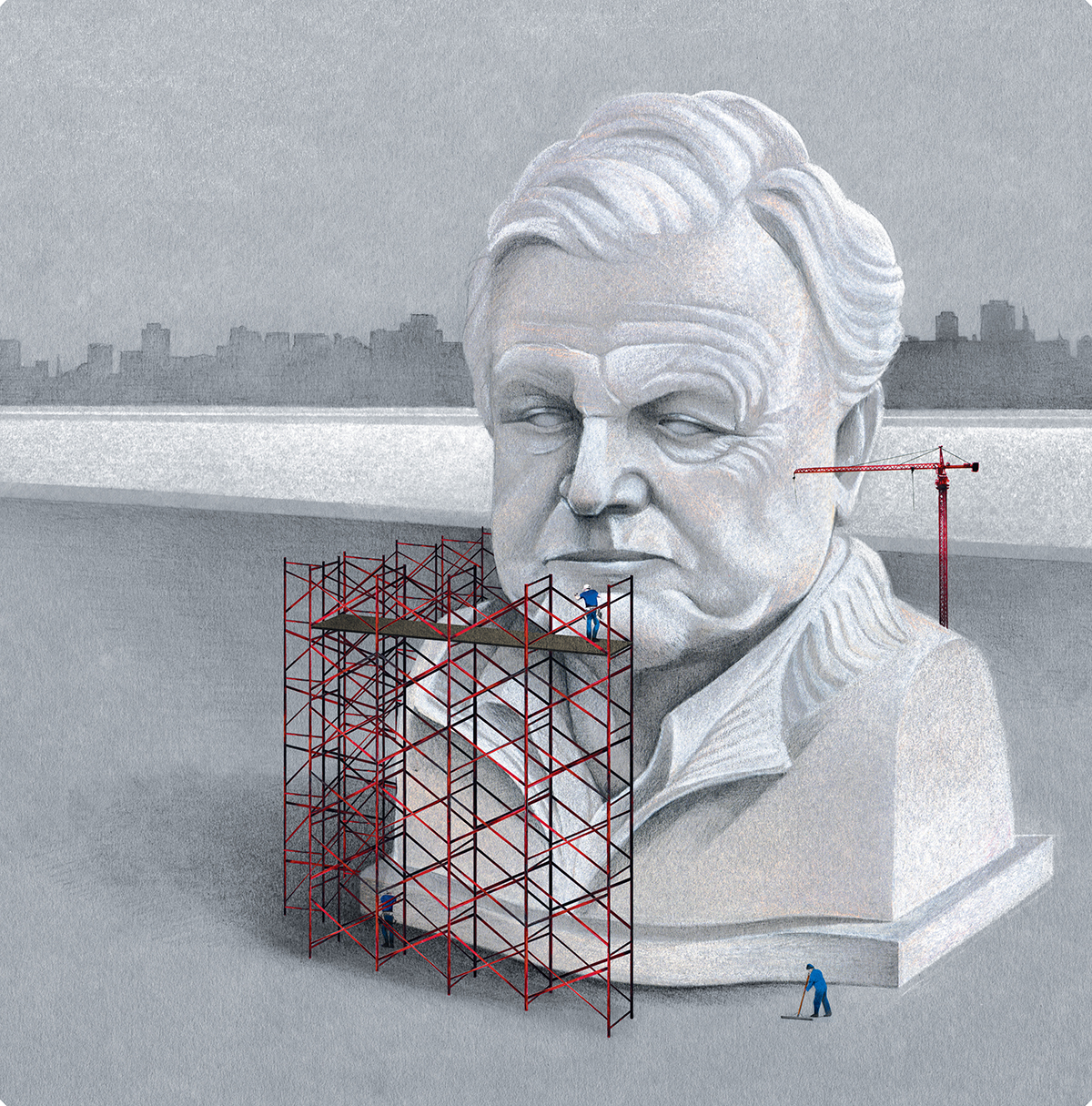

Every Legacy Needs An Architect

Illustration by Gildo Medina

Late this summer, work will begin on the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the U.S. Senate. The vision for the $50 million facility includes a full-size replica of the Senate chamber, exhibitions honoring Senate history, even in-depth tutorials for incoming U.S. senators. Going up next to the JFK Library out on Columbia Point, the institute is an act of legacy-crafting on an epic scale, a push to elevate Ted Kennedy’s to a plane ordinarily reserved for presidents, to show how he managed to break the surly bonds of the Senate and become something else altogether, something singular in impact and importance to his constituents and his country.

And the man behind it all is…the guy who used to rep former Celtics center Joe Kleine.

Meet Lee Fentress, chairman of the Kennedy Institute (to be fair, he also represented Rick Fox, David Robinson, and Len Bias). If you’re surprised that a former sports agent is coordinating this heady project, you’re not alone. “I’m really the last person to know why [Kennedy] asked me,” says Fentress, with a degree of understatement you wouldn’t expect to find in someone who paved the way for the likes of Scott Boras. “He knew I had just throttled back from my work, so I had spare time. We’ve known each other for a long time, we’d talked about a way to memorialize his years in the Senate, so he asked me to head it up.”

Fentress has been a friend of the Kennedys in general, and of Ted Kennedy in particular, for decades. The two men played tennis together most mornings for 30 years, and the senator calls him “a lifelong friend,” adding, “I’ve always valued his counsel.” Frank Craighill, an old comrade and former business partner of Fentress’s, notes the relationship has always been a close one. “He’s spent a lot of time with Teddy, and Teddy feels a great deal of confidence in him,” he says. And whether it’s of equal or lesser importance than being a FOK, or Friend of Kennedys, Fentress also has political bona fides—unusual for a man in his line of work. (“Generally speaking, we didn’t have too many political aficionados in the sports management business,” quips Craighill.) Plus, this isn’t the first Kennedy legacy he’s helped tend.

After graduating from the University of Virginia Law School, Fentress, a Louisiana native, moved to DC to take a job as an assistant U.S. attorney, where he got to know Senator Bobby Kennedy. Fentress had expected to stay in the office just a few years, but his tenure proved even shorter when Bobby announced his candidacy for president in March 1968. “I resigned that afternoon,” he says, and got on a plane and went to work for Bobby as an advance man. It was then that he met Ted. “In 1968 he was just evolving,” Fentress says. “The focus had been on Robert, but people knew Ted had great political instincts.”

Fentress mostly left politics after Bobby was assassinated. Four years later, following a stint at a small DC law firm, he joined Craighill and two other partners and began breaking into the sports management business, then in its infancy. That venture became ProServ, one of the nation’s first sports agencies. In college, Fentress was a nationally ranked tennis player—even playing in the U.S. Open—and his relationships with greats Arthur Ashe and Stan Smith set up the company to expand into other sports. “He had a wonderful touch,” says Craighill.

When Kennedy buttonholed Fentress over lunch near Capitol Hill five years ago and asked him to head up an official oral-history project chronicling his decades in the Senate, Fentress was taken aback, he says. But in retrospect it made sense: He had served on the board of the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial, chairing it for eight of those years and launching, among other initiatives, the RFK Human Rights Award. The oral history is now well under way, being carried out by the esteemed Miller Center at the University of Virginia, which has ample experience working with the biggest of bigfoot politicos, such as Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George H.W. Bush. “This is the first major oral-history project we’ve done that’s not a former president,” says the Miller Center’s James Sterling Young, who is directing the effort.

The scope of the oral history—including a target of well over 100 hours of interviews with the senator—is unprecedented. But as Kennedy’s health declined, the plan to memorialize him expanded. Kennedy “clearly needed a place to house all his Senate papers and his oral-history tapes,” Fentress says. Ed Schlossberg, who was also involved in the oral history, was pushing hard for a full institute. After a series of board meetings among top FOKs, the call was made, and the wheels began moving on the $50 million facility in Dorchester—also unprecedented for a U.S. senator.

Fentress characterizes his goal of breaking ground on the building this summer as “perhaps ambitious.” While the name Ted Kennedy does tend to open doors (the fundraising operation, spearheaded by former Hill, Holiday boss Jack Connors, is raking in money, and Fentress has been able to easily recruit heavy-hitter pols like former Senators John Warner and Jim Sasser), there’s still, by Fentress’s own admission, “a lot of work ahead.” The board of directors needs to be filled out. An executive director needs to be hired. The architect needs to be selected. The money needs to keep rolling in. Still, for all the work to be done, Fentress is quick to play down his role in the process. “I’m just helping to launch this thing,” he says. (It’s a sentiment echoed by fellow board member Paul Kirk, a former DNC chairman and Kennedy aide, who notes Fentress’s close attention to detail, efficiency, and congeniality.)

“He’s sort of under the public radar,” says Young. “He’s a very effective person, and very self-effacing in manner, but that helps him get where he got.” It may seem incongruous that an unrelentingly modest man would be tasked with building a president-size monument to a man who was never president, but sometimes the low-key approach is called for. However much he tries to duck the spotlight, though, when the Kennedy Institute opens on Columbia Point, Bostonians will come and check it out, and if it’s any good, they’ll have Lee Fentress to thank. And as far as personal legacies go, that’s not bad. It beats Joe Kleine, anyway.