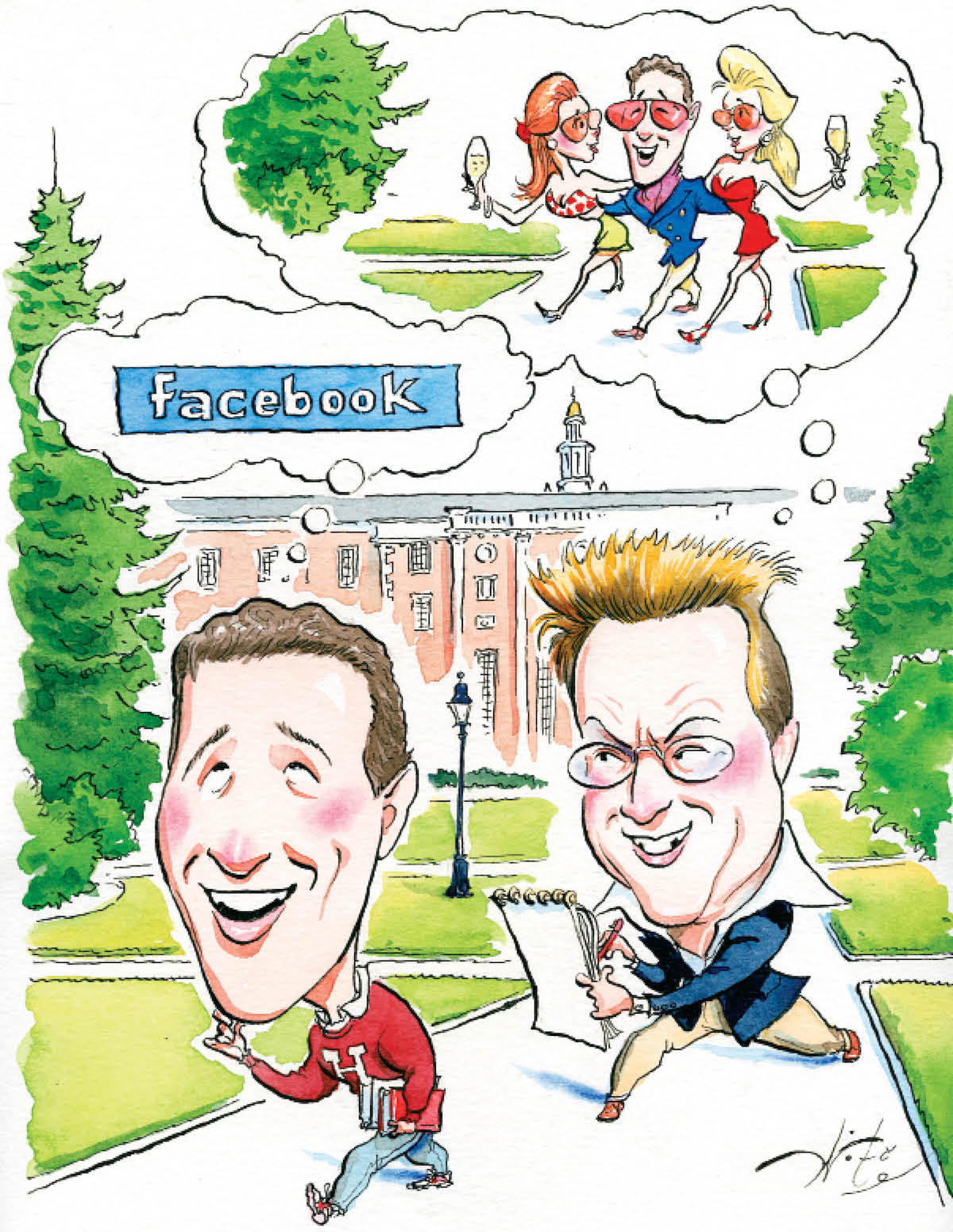

Mezrich Spins Facebook Potboiler

Illustration by Michael Witte

On July 14, a season ahead of schedule, Doubleday will flood bookstores with copies of The Accidental Billionaires, Ben Mezrich’s exposé on the social-networking giant Facebook. Hype around the book has been building since well before the 40-year-old Back Bay bon vivant started writing in earnest. Last spring, after Mezrich scored a $1.9 million advance for the project—and promptly sold the film rights to Scott Rudin, who has The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin already at work on the script—a copy of the proposal he’d circulated leaked to the tech blog Valleywag. “This is the exclusive, true story that you won’t read anywhere else,” Mezrich wrote in the proposal, which contained all the author’s familiar tropes: Sex! Money! Genius! Betrayal! (Indeed, each of those words appears in the book’s subtitle.) In one scene in the proposal, the girlfriend of Facebook cofounder Eduardo Saverin sets his dorm room on fire in a jealous rage after learning he’s been cavorting with a Victoria’s Secret model. Another vignette, set in 2004, depicts Saverin and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg feasting on koala meat on a yacht owned by the CEO of Sun Microsystems.

Notwithstanding those salacious details, the bigger intrigue has centered on Mezrich himself. Since his 2002 page-turner, Bringing Down the House, about a group of MIT geeks who win a small fortune counting cards in Las Vegas, he has cornered the market on tales of overeducated world-beaters. That book, the former novelist’s first foray into reporting, spent over a year on the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list. It was followed by three more with similar plot lines. All were sold as remarkable “true stories.”

In fact, as we now know, Mezrich gives readers “truthy.” Last year, as Bringing Down the House hit theaters as Kevin Spacey’s 21, Mezrich copped to rearranging details and creating composite characters for the book, stirring a controversy he dismisses with a touch of annoyance. “There are different forms of nonfiction. My books are nonfiction,” he says. Mezrich writes fast-paced romps that sell by the pallet, and if the literary world is semantically ill equipped to categorize his oeuvre, well, that’s not his problem. Or at least, it hasn’t been so far.

With The Accidental Billionaires, Mezrich is for the first time dealing with readily fact-checkable material, in a story about a big, ballyhooed company. Tackling Facebook’s creation, in other words, is a big step up from chronicling anonymous MIT card counters. Since he’s covering a topic that’s already been picked over by packs of journalists, he won’t hook readers by rehashing old reporting; the challenge he sets for himself is in revealing new truths—a tall order with Facebook, which has always kept a buttoned-up profile while battling a slew of lawsuits. Indeed, attorneys for Zuckerberg and his many foes have spent years in court sweating the kinds of details Mezrich usually likes to gloss over or embellish.

Not surprisingly, within seven hours of the book proposal’s hitting the Web last May, a tech journalist cried foul, pointing out that Scott McNealy, the CEO of Sun in 2004, has never owned a yacht, and therefore could not have hosted a floating bush-meat party. “It exploded before I had gotten deep into the book,” Mezrich says of the criticism, pointing out that the final product is different from his pitch to publishers. But The Accidental Billionaires, a very rare review copy of which Boston has read, bears a strong resemblance to the proposal Mezrich sold. The koala is still there, though the meal now takes place on the yacht of “one of the original founders of Sun Microsystems.” (Incidentally, each of the four founders of Sun has denied owning a yacht in 2004; the one who has since taken up sailing happens to be a vegetarian. The scene is completely false, say sources close to Facebook.) What’s more, in the book it’s Zuckerberg, not Saverin, who scores the unidentified lingerie model. “Some of the writing about Mark Zuckerberg and the creation of Facebook is more accurate than others,” says Elliot Schrage, the company’s vice president of communications. “This book appears to fall in the ‘others’ category. We think future efforts will tell a better and more accurate story.”

To cover himself, Mezrich opens The Accidental Billionaires with a 285-word author’s note that reads like a mea maxima culpa, admitting he’s again fudged facts to fit his idea of a good yarn. But to him, this wanton juking of details, dialogue, and chronology doesn’t make his chronicle of Facebook any less credible. “What’s in my author’s note doesn’t mean the book isn’t nonfiction,” he says. “It’s a true story.”

Actually, the back cover of The Accidental Billionaires bills it as an “incredible” true story. In shoehorning the tale into his narrative formula, though, Mezrich stops well short of providing the definitive book on Facebook. Such a book would flesh out the intelligent, dynamic characters—all flawed in interesting ways—who built this billion-dollar social network. Such a book would explore the mysteries that lie at the heart of the company’s founding and would at least try to answer the Big Question: Is Mark Zuckerberg a genius, a thief—or a bit of both? That’s a hard book to write, and rather than untangle any still-unresolved controversies, Mezrich mostly steers clear of them and heads into the familiar waters of libidinous hijinks. The result is a book that doesn’t live up to its billing: It’s not all that true, and not all that incredible. This time, Mezrich’s primary sin as author isn’t that he’s larded his sexed-up story line with half-truths or pure fancy. It’s that he largely ignores the stuff that would have made for an actual thriller.

Mark Zuckerberg’s rise to business titan began in 2003, when the then Harvard sophomore designed “Facemash,” a computer program that let users rank the attractiveness of undergrads by comparing photos that Zuckerberg downloaded from the school’s servers (an act Mezrich hyperbolically portrays as legend-caliber hacking). Zuckerberg’s exploits got him into trouble, but they also attracted attention. Fellow students Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss, twin rowers who would compete for the United States in the 2008 Olympics, had been working on an online social network for about a year with their friend Divya Narendra, a polymath from Queens. They needed a good programmer to finish the site, which would eventually be called ConnectU. In November 2003, they contacted Zuckerberg, who agreed to help the budding entrepreneurs.