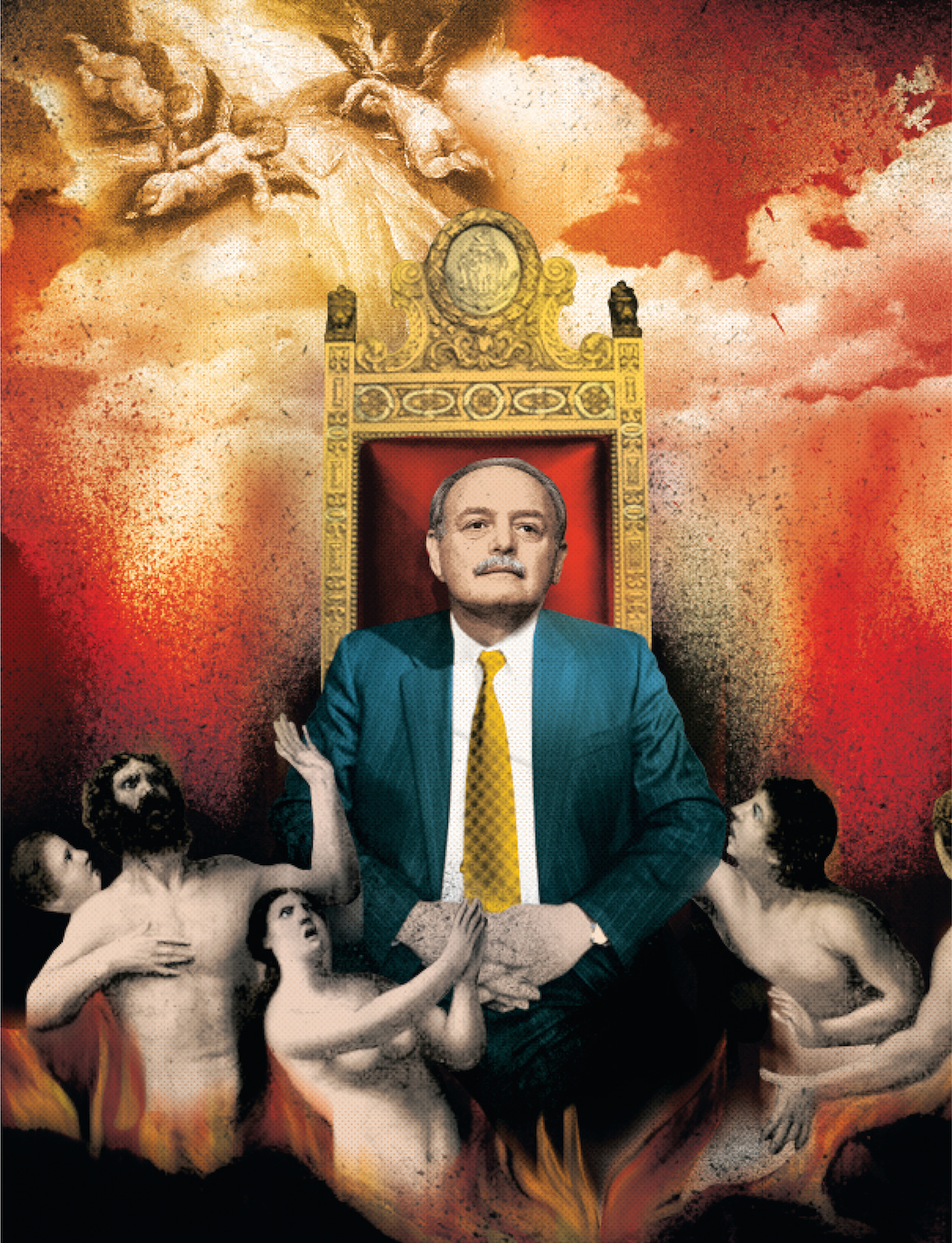

The Devil in Sal DiMasi

Illustration by Gluekit

There was always golf to play—and now there is only that. Sal DiMasi can still lose himself in the game, a whole day out here under the sun, roasting away. His colleagues in the Massachusetts House of Representatives laughed when he said that by the time Bob DeLeo was sworn in as speaker he’d be on a golf course in Florida. He wasn’t kidding. The sky over the Palm Beach area breaks wide and blue and sunny; one of the driest Januarys on record may yet threaten to set the whole state ablaze with wildfires, but out on the tee box it only means DiMasi can push his ball even deeper into the warm afternoon.

He loves the tan he brings back to Boston, friends say. But the game also satisfies a visceral need to compete, to win. He took it up as a teenager, when a tackle into a concrete wall during a touch football match in 1961 or ’62 effectively ended his otherwise promising gridiron career at Christopher Columbus High. Almost 50 years later he still has an athlete’s grace—a lolling, confident, full stride—and an athlete’s intensity. Most lobbyists, dignitaries, and fellow politicians know that if you’re playing with DiMasi, you’re not to discuss business on the course.

But apparently not every playing partner kept as quiet. A federal indictment released last month, accusing DiMasi and three associates of wire and mail fraud, depicts the then speaker receiving $57,000 in exchange for two software contracts’ passage through the House and into law. At least one of the alleged conversations about how best to do this—between DiMasi and a consultant acting on behalf of the Canadian software company—happened on a golfing trip in Naples, Florida. They happened elsewhere, too. Over e-mail and by fax and courier, according to the indictment. These alleged conversations—”It’s about time we got business like this”—portray DiMasi as a greedy louse, trading on a 30-year career that was as outsize as the man himself for checks from a lobbyist named Dickie, funneled through a DUI lawyer in a mangy downtown office.

What the indictment doesn’t show, what no one knows, is the personal financial strain DiMasi was under when he allegedly accepted the payments. In fact, if DiMasi hadn’t taken out a loan in 2006 from one of his codefendants, for the most prosaic of reasons, the whole chain of events would likely not have happened: no scandalous headlines in the Globe, no resigning under pressure, no stunning indictment. The man would have stood a great chance of still sitting in the speaker’s chair, of enjoying his golf without distraction.

But he got sloppy, the sort of slovenly corruption that attends absolute authority. With Salvatore F. DiMasi, that was the kind of authority he loved.

It was spelled out in the indictment but known long before then, mostly by the few poor souls who dared oppose him: DiMasi could push through any bill he wanted. The understanding that he would get his way was so complete in the House, it actually predated DiMasi’s reign as speaker. He in fact attained the seat through the tyrant’s oldest trick. He stole it.

By 2004, then-Speaker Tom Finneran was in trouble. After each federal census, legislative districts are redrawn down to the state district level. Two lawsuits alleged that following the 2000 count, Finneran had drawn the lines in a manner that deprived minority neighborhoods of fair representation. Finneran, under oath, had pleaded ignorance; few had bought that, and many members were calling for a new leader. That September 24, DiMasi, Finneran, and John Rogers, chair of Ways and Means at the time, met at DiMasi’s North End home in secret to decide on one. The three kept the secret well; this is the first full accounting of what happened that night.

Finneran, out of character, was 20 minutes late: As he was putting on his jacket back home in Mattapan, his wife, Donna, told him to wait, see if DiMasi and Rogers, friendly enough with each other, could work things out on their own. But when Finneran finally walked into DiMasi’s condo on Commercial Street, past the kitchen and into the dining room, he saw the two struggling at small talk.

Where the hell have you been? Rogers thought. He and Finneran had the most peculiar relationship in the House, an almost familial bond. In 2002 Finneran had taken to the House rostrum to discuss the state budget and instead delivered a weepy soliloquy about Rogers, “the son I never had.” Years later, a former House member still remembers the scene vividly. “One lobbyist told me that she was so grossed out by the speech,” the former member says, “that if she had been the wife of Finneran or Rogers she would have hired a private detective to follow them.”

DiMasi and Finneran had been close, too, but never to the point of it becoming unseemly. Both from Boston, they sat next to each other as freshmen in the House chamber, where DiMasi realized when he was in law school, he’d kicked Finneran’s older brothers out of the bar where he’d worked as a bouncer. The ties he and Finneran forged helped them orchestrate the coup that placed George Keverian in the speaker’s chair in 1985. In the 1990s, they grabbed their own power. By 2004, DiMasi was Finneran’s majority leader.

Finneran took a seat at the head of the dining room table. But then Finneran, in another un-Finneran move, chose not to direct the meeting. He was too close to these two men to pick a favorite. Besides, if Finneran were to eventually set up that lobbying practice, he would need a good working relationship with his successor. So the three men instead talked about the institution, how they were all institutional men, and how the institution of the Massachusetts House of Representatives must not debase itself with a rancorous (if democratic) battle for speaker. What the institution needed was an orderly transfer of power, they decided. People close to Rogers and Finneran say the agreement was as follows:

DiMasi was 59, Rogers 39. DiMasi would have his shot at speaker and serve until he got tired, or bored—or, given the ultimate fate of Finneran and his predecessor, indicted—at which point the mantle would pass to Rogers, who in the interim would be second-in-command, as majority leader.

But when the committee appointments came out in January 2005, Rogers was not second-in-command. That position was one DiMasi created overnight, speaker pro tempore; he’d assigned it to Tom Petrolati of Ludlow. DiMasi gave Petrolati the spot to serve as a buffer between him and Rogers. For Rogers, the move meant he was effectively out of House leadership. It meant the agreement was off. It meant DiMasi would have what he wanted most, what Rogers, because of his own ambitions, could never hand him. More power.

DiMasi never had any qualms about his decision to oust Rogers from leadership. He and his staff swear there was no deal, only an informal understanding that DiMasi would be speaker first. Still, the move to put in Petrolati was part of a larger strategy.

DiMasi picked his lieutenants for their loyalty. Petrolati, or Petro, as he is commonly known, may have been the best example. A short man with slicked-back hair and a closet full of natty suits, he was a purely political animal under DiMasi, not at all keen on policy. He whispered about DiMasi’s omnipotence to fellow members, and what folly it would be to challenge that before the full House, or in a caucus, or ever, really. Notice would be paid, and perhaps, as in the case of former Arlington state Representative Jim Marzilli, who dared to author an energy bill without DiMasi’s approval, a title of vice chairman stripped.

Other members expressed their loyalty in other ways. Take Bob DeLeo, the current speaker. He was chairman of Third Reading, the committee charged with ensuring proper grammar in every bill, when DiMasi assigned him in 2005 to be head of Ways and Means, the most important chair in the House. “Those of us who have watched him as a friend,” says Josh Resnek of the Winthrop Transcript, who’s known DeLeo for 30 years, “can’t help but say he was the quintessential backbencher.” Before DiMasi tapped him, DeLeo was mulling a departure from the legislature to become a district or state judge, a person close to him says. But DiMasi saw an ally who would live by old codes: The two men came from nearby, clannish Italian neighborhoods, places where fealty was valued.

As Ways and Means chair, DeLeo was the rep who introduced a bond bill in March 2007 that contained a provision for one of the now-infamous software contracts that have DiMasi in all this trouble. The opaquely worded amendment required the state to find a firm that would provide a “performance management system” for $15 million. The firm DiMasi wanted, the federal indictment alleges, was the Canadian company Cognos. The indictment further alleges DiMasi wanted Cognos to get this contract because he had been paid—through the help of a Cognos lobbyist, a Cognos consultant, a Cognos sales agent, and a lawyer on Cognos’s payroll—an average of $4,000 a month by the company between 2005 and early 2007.