Dispatch: The Body In the Cove

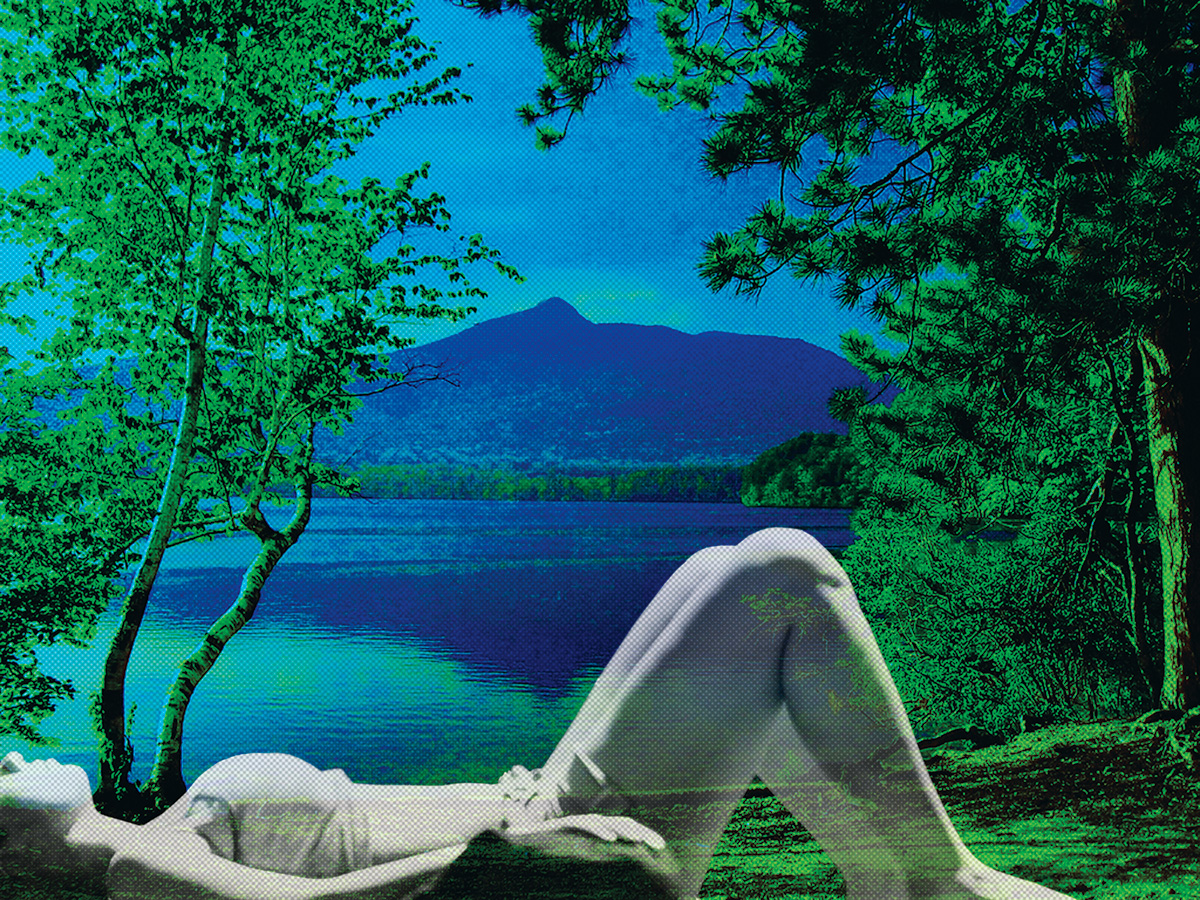

Illustrated by Heather Burke

Jen Cannon, out on the raft, thought it was a rock, a flat rock near the surface of the water. But her husband, Lee, didn’t think much of it. One of the Cannon clan from the upper road, Lee had swum in this part of New Hampshire’s Chocorua Lake hundreds of times, as had his parents and grandparents before him. “There’s no rock over there.” He lay back next to his wife and let the August sun beat down on him. He would have remained there on that raft, letting the gentle waves rock him the whole afternoon, if he hadn’t heard the shouts.

They came from a couple of kayakers who had been picking blueberries along the shore. Lee had never heard shouts like that on the lake. “There’s a body here!” one of them was yelling. “Looks like she drowned!”

Frantic, Lee dove into the water and scrambled toward the rickety piers that run out into the water, where he retrieved his cell phone and called 9-1-1 while one of the kayakers—he never did get the guy’s name—guided the body to shore. There, the dead woman’s blond hair billowed in the shallow water, which sloshed over her shiny white tank top and rumpled cutoff jeans. A woman in her thirties, looked like. Her body shifted a little with each ripple of the lake. It didn’t seem like she was dead, more exhausted. So exhausted she couldn’t even breathe.

About a half-dozen emergency vehicles responded, lights on, sirens going, all of them jouncing down the rutted two-track path that led to the shore. State troopers and local police fanned out to take statements while the EMTs lifted the body onto a gurney and then into an ambulance, which would take it to nearby Concord for an autopsy. This time, the ambulance’s lights were off and the sirens silent. There was obviously no rush.

An unassuming village on the southern fringe of the White Mountains, Chocorua is about two hours north of Boston, and has served for generations as a refuge for harried urbanites. The philosopher William James was one of the early ones, and today Chocorua is an attractive gathering spot for overeducated Cantabrigians eager for invigorating tramps along the mountain trails or restful soaks in the lake. It’s a knockabout place, where the residents take pride in not being fussy, the opposite of a scene like Northeast Harbor on Mount Desert Island, with its matching cocktail glasses, or Martha’s Vineyard, crawling with celebrities. Chocorua is a place to wear 20-year-old sneakers, drink gin and tonics out of plastic cups, and disappear. In that way, it’s not unlike many of New England’s most cherished refuges: hidden little enclaves steeped in tranquility.

Like most such places, Chocorua has a history of trouble with outsiders. Indeed, it was an altercation in 1876 that led to the creation of the present-day summer community. Back then, some boys from town liked to splash about naked in the lake. This was not appreciated by a Mr. Sylvester Cone, who owned the house across the road from the southern shore. He threatened to shoot the boys if they didn’t cut it out. They laughed and continued their skinny-dipping. Cone did come back with his gun, and he shot one of them dead. After he went to prison, the court put the property up for sale.

A prominent Boston financier named C. P. Bowditch pounced on the bargain, and then added an enchanting shingled mansion, briefly called Toad Hall, that is still owned by his descendants four or five generations later. The whole area is now thick with Bowditches; some have interbred with eminent Cambridge families, adding intellectual capital. Until her death four years ago at 95, the matriarch of the entire Chocorua community was the Bowditchian Cornelia Wheeler, who ruled over the tribe with her blaze of white hair.

The loyalties of the many Chocorua families—whether descended from C.P. and the business colleagues and friends he lured here, or from arrivistes like William James—go every which way, as such loyalties do. What they all share, though, is a devotion to the landscape, especially to the corner of the lake where the Cove is located. The shore is owned by the Wheelers, they of Bowditch descent, who have allowed other families to put up ramshackle bathhouses, to picnic and swim. It is a lovely spot, the ground blanketed with pine needles, the air nicely cool under the canopy of branches. But for everyone it’s the raft that is the point of reference, a kind of altar to summer. Taken in every fall and replaced every spring, it is anchored about 50 yards offshore. Buoyed by plastic canisters, it rides high off the water, offering a sort of salvation to swimmers who lunge onto its sun-baked deck.

For days after the body was discovered, people wanted to know everything about it, and they wanted to know nothing about it. It was like the snapping turtles sometimes seen around the raft: fascinating and terrifying in equal measure. Inevitably, a story emerged. The day before her body was found, the woman had parked by the public beach on the far side of the lake, by Route 16, where summer people rarely go. Charlie Worcester, of the Pennypacker clan, had sailed across the lake on his Sunfish, and noticed an attractive woman with California-blond hair perched on a boulder by the water. Being single, Worcester thought he might invite her to join him for a sail. But then he noticed something that put him off. She waded into the water and picked up a stone from the lake bed. She gazed at it, dropped it, and then stared off into the trees. She did this again, and again, and again. He brought the Sunfish about and headed back toward the Cove.

After Worcester left, the woman pulled on a small knapsack and stepped back into the water. Following the same path he had taken, she made it across the lake, and spotted the raft.

When she pulled herself up its steps, a college professor named David Helm was already there; he was puzzled to see someone swim with a backpack. As the woman stretched out on the raft to dry herself, he was struck by how trim she was, with well-defined muscles. As a teacher, Helm had learned to turn away from such sights. He chatted with her amiably, joking about how hard it must be to swim with a backpack, and she laughed back that, no, it wasn’t exactly the best idea. She’d put her sandwich in her pack, and look, now it was sopping. Still, despite all the geniality, his dominant reaction was territorial. I’d better police this a little bit, he thought.

Before long, Helm swam back to shore, leaving the woman to take in the sun by herself. He returned a few hours later, this time with his brother Lloyd and Lloyd’s two young children, eight and six. By now the woman was flat on her back, and not moving. She had a bottle of Mike’s Hard Lemonade beside her. Helm figured she’d had a bit too much. But she was more than just asleep, because the kids made quite a commotion out there, dashing around, drenching everyone with cannonballs. The woman didn’t stir.

A friend of the Helms came by in a canoe to take a picture of the family. As the photographer approached, the woman on the raft suddenly lurched bolt upright. She didn’t open her eyes, but she ended up plumb vertical, exactly in profile for the camera, facing away from the group. Her hair was in a tight bun, and, to the camera, she seemed somehow detached, superior.

The moment the photo was taken, the woman slumped back down again. That’s when one of the kids noticed something. “Why are her feet tied together?” the older boy asked. Helm and his brother looked down, and it was true. The woman had bound her feet loosely with a drawstring from her backpack.

Before long, the Helm party returned to the shore. When the children wanted to swim out to the raft once more, their mother, fearful of the strange woman, told them no. As the shadows stretched across the Cove, the Helms headed home. The woman remained on the raft.

It’s not known what she did that night. Perhaps she slept right through to morning on the raft, somehow ignoring the cold that comes on at night even in midsummer. She might have roused herself to swim back to her car to sleep, although that is hard to imagine. Maybe she came ashore at the Cove for the night, oddly unbothered by the inhospitable terrain. All of these explanations are unsatisfying. Murder leaves at least one witness; suicide does not.

It was the next day, shortly after 1 p.m., that Lee Cannon and his wife were out on the raft and the kayakers discovered the backpack floating on the water—and the body under it.

After the EMTs took the body away and the investigators finished their interviews, they said nothing about the case, leaving the larger story of who the woman was and where she had come from untold. It wasn’t until the next week that the Conway Daily Sun ran an item that filled in some of the gaps. The woman’s name was Jennifer Wetzel. She was 35. She’d been a waitress in nearby North Conway. And the police were calling the case an “apparent suicide.”

Then, more details: She’d reportedly been on antidepressants, and besides the hard lemonade had emptied two bottles of sleeping pills. She was from a small town in Pennsylvania and had trained to be a nurse, but then married a timber framer and gone with him to Vermont to rebuild a barn before settling in various parts of New Hampshire. Chafing at her marriage, she had been drawn to an ex–state trooper named Arnie who rode with a local motorcycle gang.

One day, she’d simply roared off with him on his bike. When they broke up a few weeks before her appearance at the lake, she’d slept on his couch. She had no other place to go. Near the lake, a goodbye note, addressed to Arnie, was found in her car.

It’s a sad story, and a disturbing one, one that has roiled this Chocorua community with its mix of tragedy, guilt, and effrontery. One that, in the popular mind, has turned this suicide into something closer to murder. A murder not of a person, but of the peace and tranquility that the summer people had counted on here. “How dare she?” That was one man’s summary of the general reaction.

Cruel as that may sound, few other summer places would have responded differently. For it’s not Chocorua, but rather the whole enchanted idea of an idyllic community that may be at fault. It is tripped up by a paradox: By its very nature, a landscape of undisturbed beauty endangers the peace it fosters. The more attractive it is, the more it pulls in people who the natives feel don’t belong.

Swimming into the Cove, Jennifer Wetzel unwittingly upset the order of things. She was an outsider, and to the summer people her intrusion was more than wrong. It was somehow scary, like the appearance of some monster from the deep, and it became all the scarier when she behaved in disturbing ways. That she posed a threat only to herself never dawned on anyone. To them, her mere presence put at risk their fundamental belief that this glorious spot at the foot of an exalted mountain was, by dint of history, theirs alone. And who would not feel the same? On this side of paradise, that attitude is pretty much universal.

You might even say it goes with the territory.

John Sedgwick is a contributing editor of Boston magazine. His next book, Sex, Love, and Money: Revenge and Ruin in High-Stakes Divorce, coauthored by Gerald Nissenbaum, will be published next year.