Billy Idol

Photograph by Matt Hoyle

The Weathervane Tavern in South Hamilton is the kind of crusty neighborhood place that’s accessorized with lanterns and wreaths that may or not be left over from last Christmas. Today it’s packed with a lunchtime crowd of gray-haired ladies and North Shore families, all utterly jazzed for the one and only Billy Costa, who’s here to tape a segment for his local-cable food show, TV Diner. Costa will do a few hundred of these segments a year: In the parlance of his weekly restaurant-hopping show, they’re called “destination spots”—and they represent the backbone of his program, each one an opportunity to spend a few moments gushing over some cream sauce or spaghetti Bolognese.

Costa is greeted here as if he’s a gift from God. People jump and clap; some blush as they ask for a photo. Out from purses come the cell phones and what must be the last disposable cardboard cameras on earth. Costa never misses a cue, never resists a chance to flash a showman’s grin. “The paparazzi is here!” he says, his toothy smile filling the viewfinders. And in no time, his own cameramen are rolling while he carries on about the “ALL-YOU-CAN-EAT STEAK TIPS!”; he’s seemingly mesmerized by “A MOUNTAIN OF SCALLOPS!”; and he’s wondering to no one in particular, “WHEN’S THE LAST TIME YOU HAD A MUD PIE?!”

Most people are a little disappointed when they see TV personalities in the flesh—they’re shorter, or fatter, or have worse skin than one would imagine—but Costa looks no different in person than he does on New England Cable News or on those billboards that line the highways. Spiky silver hair stands an inch or so off his head. His skin is slightly oranged, his smile slightly plumped, his eyes slightly bugged. His animated mug tops off a 5-foot-11, 165-pound frame that is almost freakishly lean. Despite the hard sell he makes for all those lobster rolls, steak tips, and mud pies, Costa hardly touches the stuff. He subsists mostly on dainty bits of tuna or a Cheez-It or two.

For the sake of today’s show, he takes a slurp of the chowder, making sure his camera guys get it. There is no script, and only a single take. That’s how Costa does it—always. He’s all about “the flow,” as he likes to say. “I’ll take live TV over taped any day; that’s where I’m most comfortable.” Of course, this freestyle approach makes pretty much every segment on TV Diner look exactly the same, but no matter. As the fans who show up in South Hamilton know, there’s comfort in consistency. Also, when you’re running on Billy’s schedule, there’s not a lot of time to sweat the details.

If you live in Peoria or Seattle or even Schenectady, you probably have no idea who Billy Costa is. But if you are one of the six million people who call Greater Boston home, you have almost certainly seen, heard, or met Costa at some point. Or you soon will. Besides the TV Diner gig, he’s a self-effacing radio sidekick on the Kiss 108 morning show, and the host of his own weekly top-30 radio program. There’s also his side job as the most enthusiastic and ever-present emcee this side of Dick Clark. “I do everything,” he says with characteristic, chest-bursting pride, “the malls, the retail gigs, the weddings, the fashion shows, the fundraisers.”

Doing “everything” has, after more than 25 years in the game, led Billy Costa to an odd sort of celebrity, one of his own creation: hyperlocal, and singular in its ubiquity. Indeed, at a moment when it’s possible to become famous instantaneously, or to become famous for nothing, Costa stands out because he is famous in one very specific place for doing the same small things—over and over and over again. For almost three decades, no store opening or used-car blowout has been too low-rent; no charity auction or tuxedo-filled party too out of the way. Nothing is too small, it seems, for a personality this big.

Long rivulets of rain streak the parking lot of the Kiss 108 radio headquarters in Medford, the water as black as the predawn sky. It’s just after 4:30 in the morning, and there are only a couple of cars in the lot. Inside, where morning radio is about to be made, trouble stirs.

“It’s the Pizza People!” Costa says, his wide eyes growing wider.

He’s in his office on the third floor, trying to pull together his morning news and entertainment reports, but for some reason he has no Internet connection. “If I come in and everything is haywire, I blame the Pizza People,” he continues. “They’re bottom feeders who leave empty pizza boxes and Chinese food cartons. These are the kinds of people who only eat pizza and subs; they sneak in here in the middle of the night and reconfigure the computers.”

Costa’s intern, Alaina, who’s heard this routine approximately 97 times before, laughs. She hops on the phone to dig up some news while he paces the office. The walls are covered with old publicity photos and posters of J.Lo, Faith Hill, Jennifer Love Hewitt, and Britney. Costa treats himself to a Zone bar from the vending machine and a small cup of coffee, confident Alaina will come up with something that he can parrot back on-air. “I never take notes, you know, physically,” he says. “I have my news written in my brain.”

The rest of the morning crew begins to arrive, and by 6 a.m., Costa, Lisa Donovan, and Matt Siegel are broadcasting the Matty in the Morning show from the studio across the hall. On the show, Siegel plays the alpha male, the funny-man to Costa’s whipping boy, while Donovan is on hand to provide a dose of stereotypical feminine sanity. Aside from some sound effects that get piped in, it’s hard to tell from the chatter in the booth when the three are broadcasting and when they aren’t, which probably explains much of the show’s success. It’s the highest-rated FM morning show in Boston, and has been for most of the past 25 years. Nearly half a million people tune in each morning.

The topic du jour is a piece of Hollywood gossip, that Morgan Freeman might have a thing for his own step-granddaughter. It’s a tidbit that Siegel finds particularly helpful in tormenting Costa, who himself is recently single. “This is Bill’s plan,” says Siegel. “Start dating a woman his own age with an eye on the granddaughter.” (As listeners know, Siegel is forever calling Costa pervy or old or gay or shameless—or some combination of those things.)

Like Siegel, Costa is dressed this morning in jeans, though his appear straight from the dry cleaner: Hard creases run the length of his legs. He’s matched his denim with a flowing white shirt made of something in the linen family. He may wear this shirt only a few more times. Billy likes his clothes as fresh and clean as possible, and he also feels it’s important to “stay current.” Besides, he has a plum endorsement deal with the North Shore menswear store run by his buddy, Alan Gibeley. “I never have anything on my body that’s not from Giblees,” he says. (He’s not including underwear here, since he doesn’t wear it—going commando makes him feel like a rebel in some small way.)

His concern about his appearance also means he’s something of a badass at the gym. He tries to get in two workouts a day. He has a peculiar aversion to other people’s sweat, though, so he chooses his treadmill carefully, preferring a buffer of two empty machines on each side. As he runs, he carries the determined look of a middle-aged guy terrified of growing a middle-aged guy’s gut. Of looking his age, in other words. And though he’s often squeezed for time, he rips a few curls and does some bench presses, then makes a beeline for the locker room to take a steam. That’s how Billy Costa rejuvenates. He doesn’t rest. He doesn’t nap. He steams.

If you find it ironic that a gym rat hosts a food show glorifying thrice-baked potatoes and double-chocolate cheesecake, you’re not alone. Costa himself finds it odd that a guy who hardly eats has made himself into a cheerleader for Boston’s most decadent foods. But that’s showbiz. You do the job they pay you to do. Watch Costa at the studio doing his weekly Kiss 108 countdown show, and a similar contradiction emerges. Costa, a gray-haired man who’s eligible for AARP discounts, holds forth on Kanye West and Lady Gaga—even though he’d rather be listening to earnest country tunes. “It really bugs me that an eight-year-old will be singing, ‘I wanna take a ride on your disco stick,’ when Mom and Dad are in the car,” he told me one day, right after introducing a song about faking orgasms and another about binge drinking. “I’ve become immune to the lyrics.”

Billy didn’t grow up dreaming he would become New England’s Dick Clark. He grew up poor in East Cambridge, where his family lived in the top apartment of a triple-decker with no hot water and no bathtub. Hockey stardom at the New Preparatory School landed him a scholarship to Merrimack College, but after two years he came home to major in communications at Emerson. To pay tuition and make rent, he scraped together some equipment and started DJ-ing events—weddings, bar mitzvahs, proms, whatever he could find. Meanwhile, he also hosted a live music show at a nightclub.

Photograph by John Wilcox/Boston Herald

After college, Costa got a shot as a DJ at WBOS, then known as Disco 93. In 1982, he pitched an idea for an entertainment news segment to a new and cutting-edge station: Kiss 108. The station gave him a chance to see what he could do—without pay—and before long it gave him an afternoon gig, which eventually led to a spot on Siegel’s morning show. “He was the fill-in guy,” Siegel recalls. “I went straight to management and asked for him full time. He brings an energy level to the show. I’ve trained myself to do this, but he does it naturally.”

A few years later, looking to break into TV, Costa launched a cable-access show called Dance Jam ’88. Before long, he was appearing on Channel 4’s Evening Magazine as well as a teen talk show called Rap Around. In 1993, Costa began hosting a small local food show on NECN called Phantom Gourmet, featuring a weekly tour of New England eateries. The show was a hit, and when it moved to Channel 38 in 2003, Costa stayed put at NECN and took the helm of TV Diner, a brand-new program that would compete with Phantom.

When he started out in the business, Costa made a deal with himself to never turn down paying work, no matter how small the gig. And so, along with the radio and TV jobs, Costa never stopped booking emcee events on the side. Today he can command as much as $1,500 an hour to host an event. Add that to the money he makes from Kiss 108 and TV Diner, and Billy Costa is, by many a measure, a wealthy man. And yet there he is, still showing up at mattress sales and bowling-alley dance parties with the same zeal he had as a kid trying to gin up rent money. “I know what he makes, and he doesn’t need to do that,” Siegel says. “He enjoys things that I wouldn’t do with a gun to my head.”

Billy recognized long ago that the jobs gave him a particularly powerful sense of satisfaction. “Early on, at live events, I realized that I felt more at home doing that than anywhere else,” he remembers. He loves the way strangers can make him feel and he’s thankful for their affection. But as he stares down 60, he can’t help but consider the cost of the life he chose. Costa’s marriage of 23 years fell apart earlier this year and, after a stretch spent living on his boat, he’s now renting an apartment on the top floor of the Salem Waterfront Hotel, overlooking the harbor. He’s got room service and maid service and he’s spruced the place up with pictures of his three boys as well as two blown-up photos: one of him with Oprah Winfrey and another of him with Paris Hilton. But he still goes over to his family’s Lynnfield house almost every day. He takes out the trash, he cleans whatever needs cleaning. He doesn’t want to talk about it, but for a guy who’s built a persona that never changes much, lately he’s been feeling the vicissitudes of life.

Photograph by Ted Fitzgerald/Boston Herald

In all the tumult, he sometimes even questions his career moves. He wonders, for instance, if he could’ve made it bigger somewhere else if he’d really given it a go. But, he says, “I had a family here and never wanted to uproot them.” Plus, the morning show was here, and constant opportunities, and his fans, too. At times, though he’s ashamed to admit it, Costa can’t help but feel a twinge of jealousy. He feels it when he turns on the TV and sees any of those competition shows, like America’s Got Talent. “I can say with great confidence that I could do that job better than anyone—that, and American Idol,” he says. “I have unrestricted confidence.”

Start pulling Costa’s cord on this topic and things circle back to the ’90s, when he was spending time out in Hollywood reporting on big events like the Grammys and the Oscars for Kiss 108, with radio stations across the country picking up his reports. Sometimes his booth was right next to Ryan Seacrest, back when he was just a radio guy, too. “The next thing you know, he’s on American Idol.”

Then there’s Tom Bergeron. In the early ’90s it seemed as if he and Costa were neck and neck as New England TV hotshots. He had the same kinds of jobs Costa did, hosting stints on local shows like Rap Around and People Are Talking. But by 1994, Bergeron was feeling squeezed out of the Boston market. He packed up his house in Belmont and moved to New York, then L.A., where he landed Hollywood Squares and then America’s Funniest Home Videos and now Dancing with the Stars. “He took a plunge that not everybody could take, that most people don’t take,” Costa says. On the radio, he and Siegel like to riff on the idea that Bergeron stole the life and career that should have been Billy’s. For his part, Bergeron finds the suggestion more immature than entertaining. “[Billy]’s good as gold. He can sit back and collect the checks and stop worrying about my career,” he tells me on the phone from L.A. “If people get upset about that kind of thing, they have too much time on their hands.”

Of course, time on his hands is not generally what Costa has. And these days he’s looking ahead, thinking about a bold move. Costa says that for the first time in his life, he wants to hire a talent agent to find him higher-profile work. Some men his age dream of getting a Porsche, others of finding a mistress. Billy Costa plans to get an agent. “I know it’s kind of late—but if there’s an agent out there who wants me, I’ll take it,” he says earnestly, almost apologetically.

The prized yachts tied up at Pickering Wharf in Salem are accessible only through a padlocked gate. Costa keeps his 54-foot Carver Voyager down here. It’s his pride and joy; even so, it took three months of convincing before he’d bring me aboard, worried that it might look showy to be seen on a boat like this during, you know, a recession (even though people who listen to Matty in the Morning already know he has a big boat, because Siegel talks about it on-air).

Billy calls the boat Off the Air, and sees it as a place to relax. After this morning’s show, he rushed here to the dock to wash the exterior, to relieve her from the heat, he says. “She gets hot,” he says. “I couldn’t wait to get there and hose her down.”

Inside, she’s predictably pristine, too. “My wife helped me decorate,” he says. The décor feels new, done up in burgundy and gold in a way that calls to mind the set of Designing Women. There’s not so much as an overstuffed pillow out of place. Billy shows me which of his kids and their friends slept where when he took them to Nantucket last week, but it’s hard to imagine kids in here. Toby Keith is singing from some hidden speakers and the air is cold, a sharp contrast to the oppressive humidity outside.

“I read that [Fox 25’s] Maria Stephanos collapsed from her five-mile run yesterday,” Costa says, by way of bringing up the weather and his own toughness. “I did a seven-mile run.” (“Extreme heat,” he says, is his favorite.) “When I read about her, that’s when I started counting down the minutes to my run today. I can see it now: ‘At least he died doing what he loved—on the hot pavement, on a scenic course,'” he says cheerily.

Photograph by Ted Fitzgerald/Boston Herald

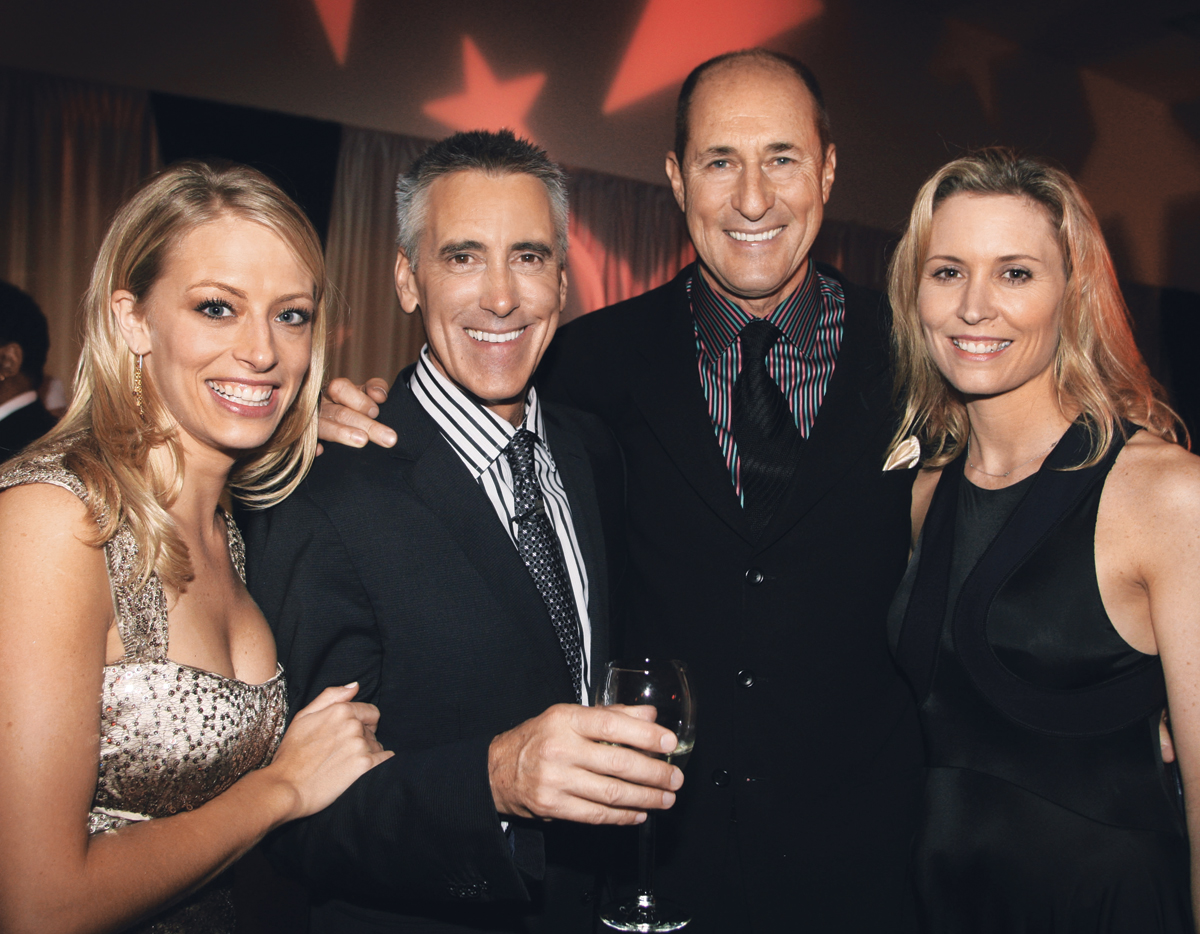

Costa stands in his kitchen nook, chin in the air, hands on his hips, looking for things to show me. I catch a glimpse of some framed pictures of his boys; his wife is in one of them, a family shot taken during a day out on the water. He swings open a small fridge and points out the “nice” wines that he keeps on hand for entertaining. Reaching past them, he grabs a Bud Light. “You want a beer?” he asks, before pouring half a can into a sturdy plastic cup. He keeps the rest for himself and starts telling me about seeing Ray Bourque at an event last night (hosted, of course, by Billy).

Suddenly, he stops and looks off to the side, and for 10 whole seconds he doesn’t say a thing. Complete silence. All I can hear is the hum of the air conditioner. Then, just as suddenly, Costa takes a sip and his internal needle hops back into its groove. That sliver of silence makes me think that perhaps it wasn’t modesty that made him so reluctant to bring me aboard. Maybe when he says this is the only place he can relax, he means it.

It got me thinking of that rainy morning this past summer, when I watched the morning show wrap up. It was just past 10 a.m. when Billy, Matt, and Lisa, along with the rest of the crew, filtered out of the studio. Their workdays over, they were all headed home—except for Costa. He would put in 12 more hours that day. “This show is my job; it’s his breakfast,” says Siegel. Being Billy Costa requires constant motion. And the life that Costa has created for himself is wrapped tightly around staying busy. “It’s really hard for anything outside of work to make me feel that great,” he says.