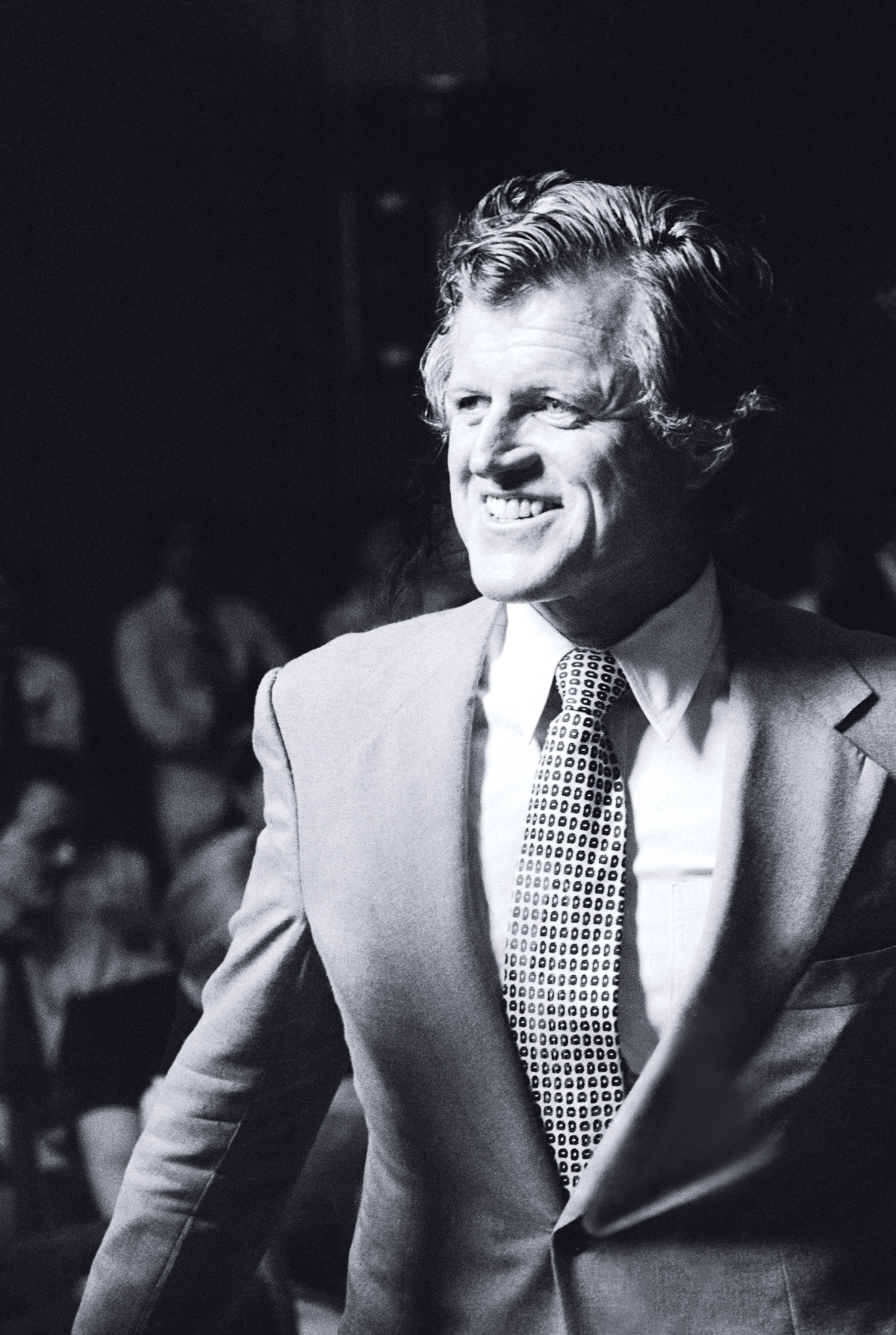

The Best Kennedy: Ted Kennedy

Photograph by Owen Franken/Corbis

Ted Kennedy often went to Mass at the church my wife and I attend in Washington. Blessed Sacrament has long been Vicki’s parish and, after she and Ted got together, he became a weekly presence there. No one paid him any special attention: He was just a guy who wore a leather jacket, taking a seat in one of the pews toward the back. It was easy to forget the history he carried with him.

That may explain my behavior during one particular Saturday Mass in November 1995. Before heading to church that evening, Kathleen and I learned that Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin had been shot and killed at a large peace rally in Tel Aviv. As Mass ended, parishioners congregated at the back of the church, and I said something to Kennedy about the shooting. He had gotten the news, too, and was saddened by it. We agreed that the priest must have been unaware of what had happened; otherwise he would have led us in prayer for Rabin and his family. I said goodbye, and then, as I walked out the door, it struck me: How could I have spoken so casually about assassination with Ted Kennedy—of all men?

The reason was that Kennedy never acted like a man who was stalked by tragedy, and in that moment at the church—rather than flinch, or shoot me a look, or do anything to remind anyone of everything he had been through—his thoughts were not about himself, but for the people of Israel, what they were going through.

I write this now because it’s an important part of understanding Ted Kennedy. That day in the church more than a decade ago was a small window into how Ted had managed to survive the twin tragedies of his brothers’ assassinations: He refused to be haunted or defined by a fear of death. A close friend of mine who once accompanied him on various trips recalls how the doors to Kennedy’s house were rarely locked; how his Massachusetts license plates grandly ID’d the senator’s car as “USS 1”; how Kennedy took the same route each morning across the Potomac River; how he never had special security; how he walked like any other senator from his office to the Capitol.

He did what Kennedys do, in other words. He soldiered on. But Ted did it longer, and better, than anyone ever had a right to expect. That’s something for which his worst enemies should stop even now and assign him credit. Alan Simpson, the flinty former Republican senator from Wyoming and a friend of Kennedy’s, once said, “If other people had gone through what he’d gone through…they’d just be sitting there drooling and staring off into the east.”

It’s also worth remembering that the tragedies in Kennedy’s life didn’t begin and end with John’s and Robert’s deaths. His brother Joe Jr. was killed during World War II. His sister Kathleen died in a plane crash in 1948. Five decades later, his nephew John F. Kennedy Jr. died after crashing his plane into the Atlantic. Then there was another nephew, David, who died of a drug overdose in the 1980s, and David’s brother Michael, who died in a freak skiing accident. And, of course, there was Chappaquiddick.

Kennedy lived with all this, all the time. Simpson remembers getting off the subway that runs between the Senate office buildings and the Capitol one day with Kennedy. A woman approached and began to berate Ted. “How do you feel about what you did with that woman at Chappaquiddick?” she yelled. Kennedy, without raising his voice, said, “It’s with me every day of my life.”

That’s the deeper truth about Ted Kennedy. He may have wanted to appear as though he were unaffected by the sorrow in his life—that he would always soldier on—but the tragedies influenced him in ways great and small, in private and public. And they did so from a young age. During a 1946 birthday celebration for Jack, whom polls showed was headed for a victory in the Democratic primary for Congress that year, Joseph Kennedy Sr. called upon each of the Kennedy brothers to offer a toast to the evening’s star. When it finally came his turn, Teddy stood up and said, “I would like to drink a toast to the brother who isn’t here.” He, alone, was thinking of Joe Jr., killed two years earlier.

Most important, though, the tragedies that afflicted Kennedy made him the kind of public servant he wanted to be, a politician who would fight for people who would never have the wealth, power, and privilege he possessed. The tragedies allowed him to know what it was like to live with a burden. It allowed him, in other words, to become Ted Kennedy.

Sarah Brady—whose husband, Jim, was the man behind the contentious Brady Bill of the 1990s—recalls how Kennedy helped in her long fight to pass gun-safety legislation. “[H]e was always working behind the scenes, lobbying his colleagues on our behalf,” she says, “yet he never wanted any credit for his efforts.” He got it, regardless. The NRA loathed Kennedy. In 2008, it blasted him as “the man who has cast more anti-gun votes than any other lawmaker in U.S. history.” That was perhaps the one thing that the gun folks and Kennedy could agree upon.

Kennedy called his “nay” vote on the 2002 Iraq War Resolution the best he ever cast in the Senate. But not for the reasons you might expect. His focus was not on just the geopolitical debate over peace and war, or even being on the “right” political side. It’s that Kennedy saw war’s personal costs more clearly than most of his colleagues.

In November 2003, he attended the funeral of John Hart of Bedford. There, Hart’s parents, Brian and Alma, told Kennedy about the lack of armor on their son’s Humvee. Two weeks later Kennedy held the first congressional hearings on body and vehicular armor. That armor is standard equipment on Humvees today. “Brian and his wife, Alma, turned that enormous personal tragedy into a remarkable force for change,” Kennedy told the National Press Club in January 2007. He could have been talking about himself.

He spent his life transforming his troubles into the nation’s gain. Seventeen years after Teddy Jr. lost his leg, for instance, Kennedy was instrumental in ushering through the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. And always there was Kennedy’s greatest sympathy: wanting to help those who lacked the healthcare that he could afford. In his memoir, True Compass, Kennedy describes how he committed himself to the issue after Bobby’s death in 1968: “I recognized that improving healthcare, and ensuring Americans’ ability to pay for it, would be my main mission, and I would fight for it for however long it would take.” Though he oversaw improvements in Medicaid and Medicare, the mission lasted longer than he could fight for it. Just as with his brother and civil rights, Ted Kennedy’s signature bill would have to succeed after his death.

In 1957, then-Senator John F. Kennedy chaired the panel that named Webster, Clay, Calhoun, LaFollette, and Taft as the greatest senators of all time. If such a panel existed today, JFK’s youngest brother would surely be at the top of that list.

Chiseled in granite near the graves of the three Kennedy brothers at Arlington National Cemetery is a quotation from Aeschylus that Bobby was known to recite. “In our sleep, pain that cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.” For the last of the brothers, there can be no better epitaph.