The Art of the Story

What Was Lost & Why It Matters

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

The Concert

Johannes Vermeer

Oil on canvas, 1658–1660

28.5 x 25.5 inches

Stolen from: The Dutch Room. The painting was lifted from its easel and removed whole from its frame.

Significance: This is a masterpiece for many reasons. First, only 34 Vermeers are believed to exist. Second, Vermeer was a master of light and mystery. “There’s an element of complexity that all great works of art have,” Chong says. “You can pick out the technicalities—we know the light falls from the left and that people singing and playing music is a traditional Dutch theme, but all those facts don’t add up to this painting.”

Worth noting: The painting on the right in this scene depicts a real work, The Procuress, by Dirck van Baburen, which Vermeer’s wealthy mother-in-law once owned—and which now, astonishingly, hangs in our own MFA.

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

Rembrandt

Oil on canvas, 1633

63.7 x 51.1 inches

Stolen from: The Dutch Room. The painting was lifted from the wall, removed from its frame, and cut from the stretcher.

Significance: “Much is made of the fact that this is Rembrandt’s only seascape, but to me that’s far less

important than the way the figures are arranged,” Chong says. “Rembrandt is a master of creating connections between figures as a way of telling a story. Here, he groups people around areas of light and dark; he piles them on top of each other; he makes their gazes interact. It keeps your eye moving.”

Worth noting: The artist inscribed “Rembrant” [sic] on the rudder.

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Self-Portrait

Rembrandt

Etching, circa 1634

1.75 x 2 inches

Stolen from: The Dutch Room. This piece hung from the side of a 17th-century carved oak cabinet, which stands beneath another Rembrandt self-portrait, in oils. The thieves took the time to dismantle the etching’s frame.

Significance: Rembrandt created about 75 known self-portraits, so while important, the etching is considered less rare and culturally valuable than works like Galilee.

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

A Lady and Gentleman in Black

Rembrandt

Oil on canvas, 1633

51.8 x 42.9 inches

Stolen from: The Dutch Room. The thieves lifted it off the wall, removed it from its frame, and cut it from the stretcher.

Significance: Some speculate that this was made in the artist’s workshop. “If by Rembrandt, it’s a less-than-successful society portrait of the type he sometimes had to do to establish his reputation in Amsterdam,” Chong says. “It’s an interesting painting but frankly I wouldn’t call it great. This well-to-do young couple doesn’t show a lot of spirit or energy.”

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Chez Tortoni

Edouard Manet

Oil on canvas, 1878–1880

10.2 x 13.4 inches

Stolen from: The Blue Room, on the first floor. (All the other pieces were taken from the second floor.) It was lifted off the wall and removed from its frame.

Significance: “The quick brushwork,” Chong says. “Like his colleagues, Manet was interested in contemporary life, the current scene in Paris. To me, this is [interesting because it’s] partly a portrait, partly a scene from everyday life.”

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Landscape with an Obelisk

Govaert Flinck

Oil on oak panel, 1638

21.5 x 28 inches

Stolen from: The Dutch Room. It was lifted from its easel and removed from its frame.

Significance: The painting only recently was attributed to Flinck; Isabella Gardner died believing it was a Rembrandt. “Flinck was a follower of Rembrandt, and his landscapes are different from other 17th-century Dutch landscapes because they’re so energetic—they’re about light and shadow and great billowing clouds,” Chong says. “Obelisks were often used as markers, to count the distance between cities or as a division between a city and the surrounding countryside. This beam of light hits the obelisk and sort of splits the landscape; the artist may be suggesting that we’re leaving civilization and entering the wilderness, something scary and wild and emotional and out of control.”

Artwork Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

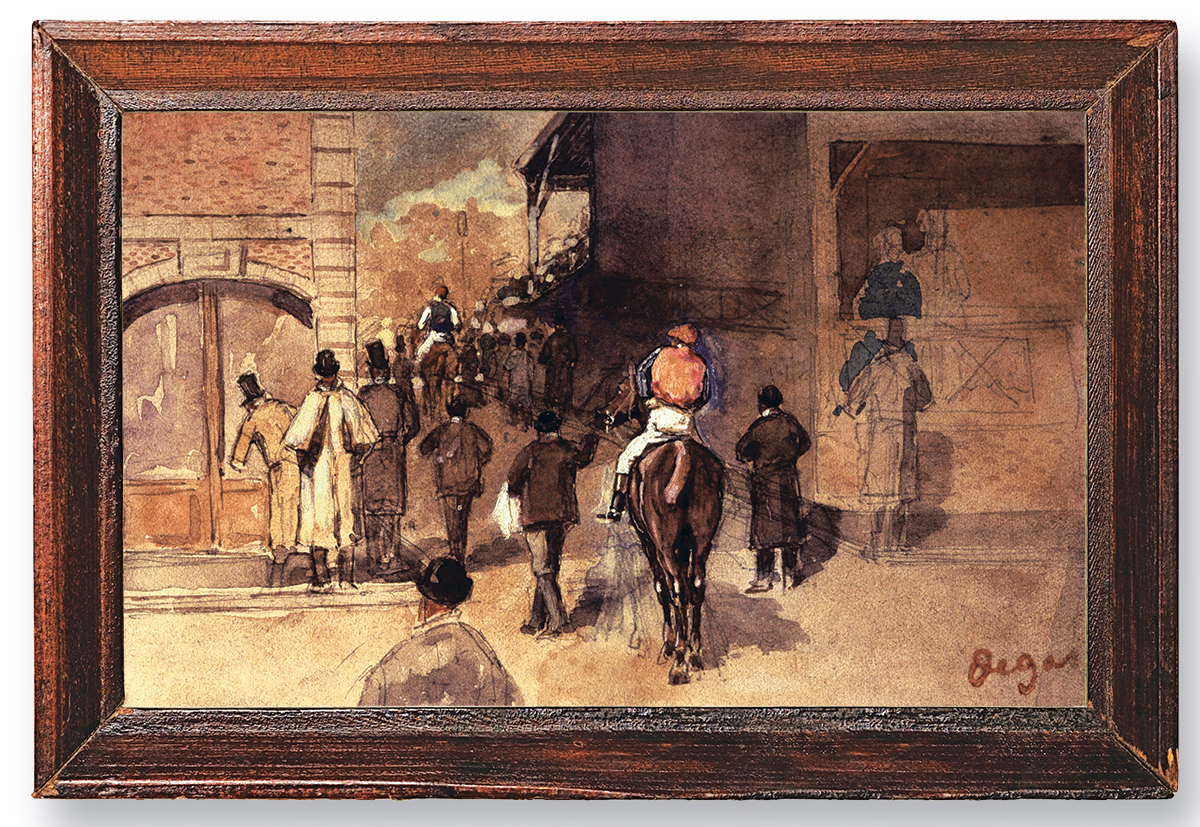

La sortie de pesage

Edgar Degas

Pencil and watercolor on paper, circa 1880

3.9 x 6.3 inches

Stolen from: The Short Gallery. Five Degas drawings were displayed in three frames, which the thieves removed from the display panels.

Significance: “This snippet of French upper-class life is not something Isabella Gardner normally collected, although she might have been drawn to it because of her love of horses,” Chong says. “She bought it in 1919, very late in her collecting career.”

Artwork courtesy of the isabella stewart gardner museum

Bronze finial from Napoleonic flagstaff

Unknown

Gilt metal, 1800s

Stolen from: The Short Gallery. The flag stood encased in glass, in the corner, between the Degas drawings and the Tapestry Room door. Some investigators believe the thieves took the heavy eagle flag-topper as a sort of souvenir when they couldn’t access the flag itself.

Significance: “Isabella Gardner collected objects associated with Napoleon,” Chong says. “He was a very strong cultural figure—he was the Elvis of the mid-19th century.” Gardner acquired the object in New York in 1880, at a time when the market was full of Napoleon forgeries. Scholars have debated whether the finial is genuine or a copy made in the same era.

Artwork courtesy of the isabella stewart gardner museum

Bronze beaker, or ku

Unknown

Bronze, 1200–1100 B.C. (Shang dynasty)

10.5 inches high, 6.12 inches in diameter,

2.4 pounds

Stolen from: The Dutch Room. Isabella Gardner displayed the ku on a velvet-clothed table beneath Rembrandt’s Galilee. The thieves had to wrest it from its heavy metal base.

Significance: Among Gardner’s Chinese pieces, her ancient ones were particularly important, Chong says. “This is the only one of that type that she had. It’s a very, very good piece. These bronzes were ritual vessels excavated, for the most part, from tombs. They may have been used in ceremonies connected with burial, or they may be replicas of things used in daily life.”