Band of Brooders

Illustration by Jesse Lefkowitz

In hindsight, Aerosmith’s 2009 tour looked like a slow, sad march to the end.

Just before it started in June, the band’s rhythm guitarist, Brad Whitford, bumped his head climbing out of his Ferrari — surely one of the lesser-known hazards of rock superstardom — and had to miss several shows. A guest musician covered for him, but then lead singer Steven Tyler pulled a leg muscle, and seven shows had to be canceled. When Tyler returned, bassist Tom Hamilton, who had been treated for throat cancer a few years back, had to leave to recuperate from minor surgery. Meanwhile, Joe Perry, the lead guitarist with the skunk-stripe hair, had been limping along on a recently reconstructed knee (at least drummer Joey Kramer had thus far escaped injury). After nearly 40 years on the road and well over 1,800 shows, Aerosmith’s five members were finally showing their age: a combined 293 years.

At 62, Tyler is the oldest of the group, and the one who has lived the hardest (which, given their legendary drug habits, is quite an accomplishment). He’d apparently been sober for more than a decade when, in 2008, he underwent surgery on his feet, which had been damaged by decades of physically demanding performances. His doctors prescribed him powerful painkillers, and “being the good drug addict and alcoholic that I am,” he said, “I was off and running again.”

Tyler soon signed himself up for yet another stint in rehab, but some of his bandmates doubted it took. His behavior became increasingly erratic. “He doesn’t act like a sober person,” Whitford said at one point last year.

The 2009 tour was originally designed to support Aerosmith’s first album of original material since 2001. But they hadn’t been able to finish the project, and there were rumors that Tyler had simply walked out of the studio. The band resolved to tour anyway. Shortly before they hit the road, however, Tyler rankled the other members by splitting with the group’s longtime manager and assembling his own team. Suddenly, two sides — with two different agendas — were directing Aerosmith’s business affairs. The move, says one of the band’s former managers, was a “recipe for disaster.” (The five still share a publicist, who declined to make any of them available for interviews.)

Although the other members of the band tried to keep their true feelings about Tyler from affecting the performances, the tension was sometimes difficult to mask. That became obvious during an August 5 show in Sturgis, South Dakota, a concert that would become the band’s most talked-about in years. Midway through “Love in an Elevator,” a fuse blew somewhere offstage and Tyler’s microphone cut out. To entertain the crowd while waiting for it to be fixed, Tyler strutted out on a catwalk and launched into an impromptu dance routine — the “Tyler shuffle,” as he calls it. As he came out of a spin, he fell to one knee, then toppled backward off the stage. Tyler was airlifted to a hospital, where he learned he’d broken his shoulder and needed 20 stitches to close a gash on his head.

Later, videos of Tyler’s fall became a minor YouTube sensation. But amid all the armchair analysis of what had happened, one curious detail passed with little comment. A full 45 seconds elapsed between the moment when Tyler fell and when a couple of roadies finally pulled him back up onstage, an interval that seemed even longer as a worried hush descended on the audience. But that wasn’t the odd thing. The odd thing was that, during those 45 seconds, not one of Tyler’s bandmates came over to see if he was okay. Perry didn’t even stop playing his guitar.

Eight days after Tyler’s fall, on August 13, Aerosmith canceled the remaining dates on its tour, and Perry went to Twitter to make clear who he thought was to blame: “I am so sorry about vocalist Steven Tyler having to cancel our Aerosmith shows.” On the same day, a haggard-looking Tyler, his arm in a sling, bought a bottle of booze at a Pembroke package store and made the mistake of posing for a snapshot with another customer, who then put the photo on the Internet. As speculation swirled that Tyler had fallen off the wagon, band insiders whispered to gossip columnists that he had spent two days leading up to the South Dakota show “partying” with various hangers-on. In response, Tyler publicly insisted that he had been sober.

Had it not been for certain business realities, the band might have called it a career right then. But Aerosmith, of course, is no longer just a band. It’s a multimillion-dollar corporation, and it was contractually obligated to perform four one-off shows in the upcoming weeks — such is the burden of America’s most successful rock group. Tyler would fulfill his commitments, but he made sure the band’s other members knew he was unhappy: He communicated through his new managers that he wouldn’t be speaking with them, and demanded that his dressing room be far from theirs. After one show in Hawaii, Perry called Tyler to say they’d been offered a chance to tour South America. Did he want to do it? Tyler said no and hung up.

Shortly after Aerosmith’s last contracted gig, a November 1 concert in Abu Dhabi, Tyler told a reporter from Classic Rock magazine that he was leaving the band to work on solo projects. “I don’t know what I’m doing yet, but it’s definitely going to be something Steven Tyler,” he said. “Working on the brand of myself — Brand Tyler.” When Perry read the story online, he told another interviewer, “Steven quit, as far as I can tell.”

After 40 years of surviving addictions, divorces, and near bankruptcies; after selling more albums than any other American rock band in history — and, by the looks of it, having more fun doing it than anyone who’d ever stepped onstage — it seemed as though Aerosmith was finally over.

To anyone who has paid much attention to Aerosmith over the years, the most recent dramas weren’t altogether unexpected. The band has pretty much operated as a wildly dysfunctional family since the beginning. At some point or another, each of the five members has had to be talked out of quitting; and each has had to be assured that he was absolutely essential to the group’s survival. But even the rhythm section, made up of Whitford, Kramer, and Hamilton — who early on began calling themselves “the Less Important Three” — would agree that their enterprise revolves around Tyler and Perry. “The relationship between Steven and Joe is really the axis of the whole thing,” says a former band manager.

Musically speaking, the singer and the lead guitarist couldn’t have been more different. Before he formed Aerosmith, Tyler was already a polished drummer with a deeply ingrained musical discipline instilled by his father, a Juilliard-trained pianist. Perry, in contrast, was a self-taught guitarist from a family that barely ever turned on its record player. In the summer of 1969, Tyler saw Perry’s group, the Jam Band, perform in Sunapee, New Hampshire, and found them terrible — out of tune and sloppy. But during a song called “Rattlesnake Shake,” Tyler had an epiphany. “There was just something about the way Joe played it, this whole fuckin’ train feeling,” he recalled in Aerosmith’s autobiography, Walk This Way. “I thought, If I can put that energy together with something my father gave me, that classical influence, we might have something.”

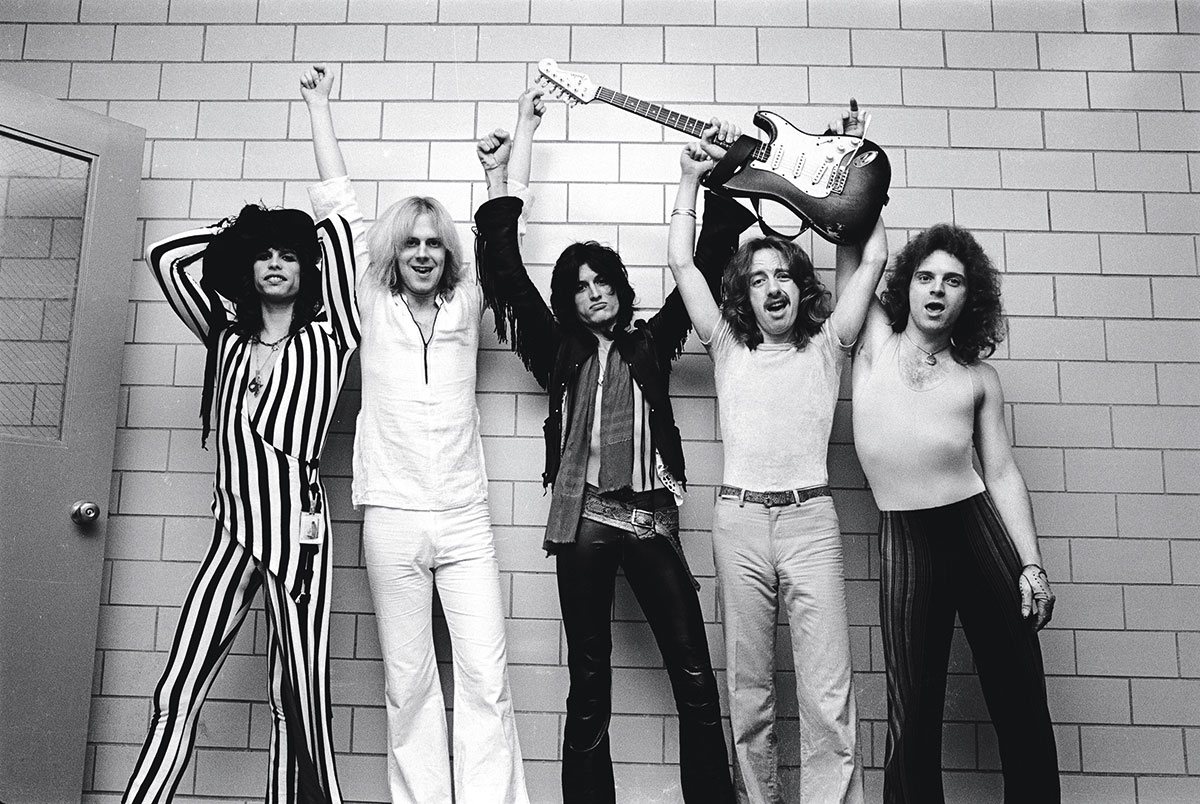

Tyler persuaded Perry to quit his band and form Aerosmith. They moved into an apartment on Commonwealth Avenue in Allston with Kramer and Hamilton. Tyler traded his drum kit for a microphone and set out to mold the group according to his vision. “He was the dominant force in the band ‘family’ with great expectations for the band that he loved, as well as for everyone in and around it,” Kramer has written. “But Steven could be punishingly critical when those expectations weren’t met.” During recording sessions, he perched himself on a high stool, his dark, deep-set eyes alert to any signs of weakness, like a raptor. “I taught them how to be a band. They’ve hated me for it ever since,” Tyler once told an interviewer. “You laugh, but there’s been lots and lots of therapy over this.”

The first two Aerosmith albums didn’t get much radio play, so the band had to build its name through constant touring. All that time on the road provided plenty of opportunity for Tyler’s and Perry’s personalities to clash. “Joe is kind of demure and laid-back, where Steven is flamboyant and outrageous,” says Raymond Tabano, the band’s original rhythm guitarist (whom Whitford replaced in 1971). “You put those two things together and you’re going to get friction, and when you get friction you get sparks, and when you get sparks you get a fire.”

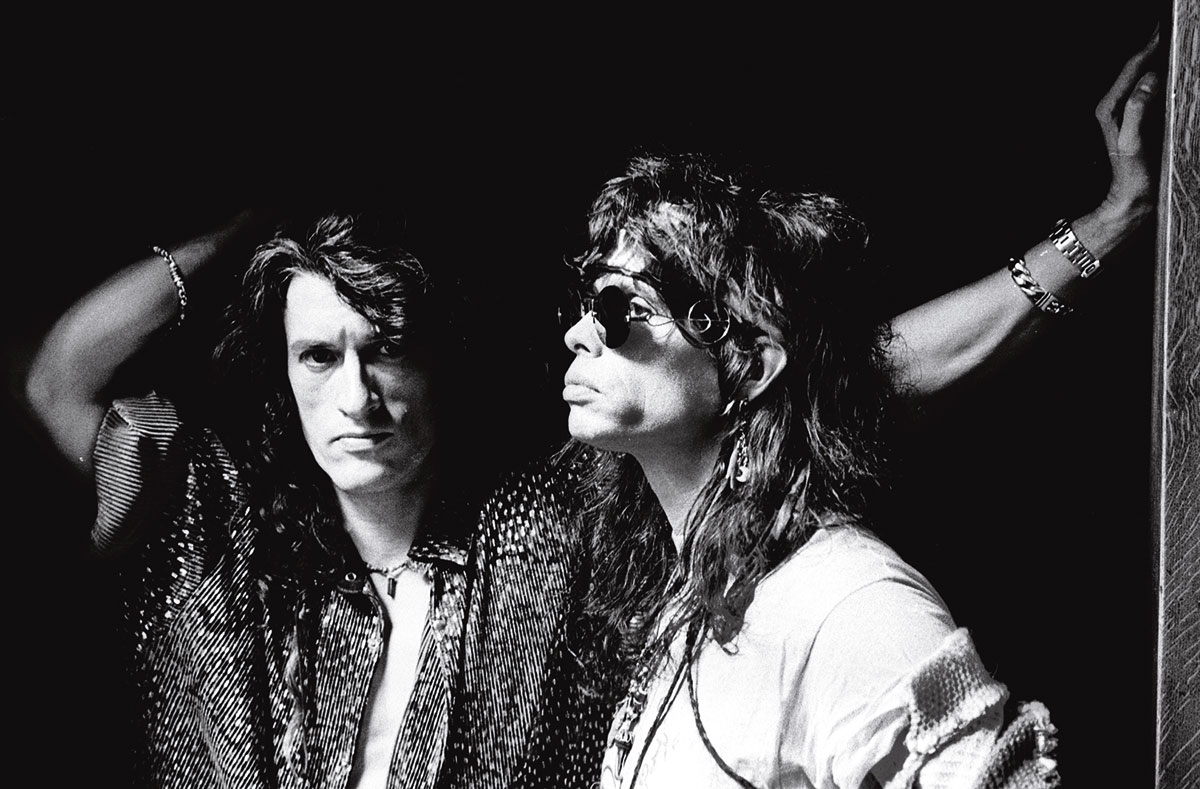

Photograph by Chris Walter/Getty Images

From the beginning, Tyler and Perry fought incessantly, over musical issues and personal ones. But once they were in front of a crowd, they funneled that aggression into electrifying shows. “When they were [onstage] there was love between them, there was chemistry. They fed off that intensity,” says Steve Leber, who managed the band from 1972 to 1984. Their shows started attracting ever-larger hordes of denim-clad teenage boys — “the blue army,” as the group always referred to them — drawn to the band’s good-time message of sex and rebellion. Twenty thousand fans showed up at Madison Square Garden, 90,000 at Michigan’s Silverdome. After albums like Toys in the Attic and Rocks became massive hits, the crowds suddenly numbered in the hundreds of thousands. By the end of the 1970s, Aerosmith was the biggest band in America. Tyler, Perry, Whitford, Hamilton, and Kramer were millionaires.

Then everything fell apart. From the earliest stage of their career together, the members of Aerosmith, like many of their contemporaries, used and abused drugs. But the band’s financial success had the unfortunate side effect of pushing Perry and Tyler from highly functioning addicts into full-scale junkies. In 1978, before headlining a show for 350,000 people in Ontario, California, Tyler sent a roadie back to Boston on a Learjet to retrieve his stash; the roadie returned just before Aerosmith took the stage, and Tyler got so wasted he couldn’t remember his lyrics. At that concert and others, he and Perry were going through the motions, trying to talk themselves out of doing an encore so they could get high that much sooner. To get through the shows, Tyler often stowed drugs in the scarves tied to his mike stand; Perry kept a vial of cocaine on his amp and would dip into it when the stage lights dimmed. The drug abuse got so bad that the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, a noted authority on such matters, judged Aerosmith “the druggiest bunch of guys I’ve ever seen.”

As the band grew more successful, the clash between the drug-fueled egos of Tyler and Perry escalated. Spending any time together offstage proved nearly intolerable — the relationship between the “Toxic Twins” had turned poisonous. It didn’t help that Perry’s wife, Elyssa, was saying he was such a big star he didn’t need Aerosmith, while Tyler’s wife, Cyrinda, was telling him pretty much the same thing. (To Kramer, it felt like touring with two Yoko Onos.)

The situation was not without its conspicuous subtexts. Like a jealous girlfriend, Tyler resented the time Perry spent with his wife. A former manager says Tyler sees his relationship with Perry as a “creative love affair, a marriage without the sex.”

Later, Tyler would admit he “was really hurt that [Perry] would rather be with [Elyssa] than be with me. Especially after we sat on a waterbed and started writing songs.” Because, Tyler added, for him “writing songs was fuckin’.”

No matter how terrible life on the road with Perry became, Tyler couldn’t imagine doing anything else. The same thing, however, couldn’t be said for the guitarist.

In the summer of 1979, the band got into its biggest fight ever, the circumstances of which have gone down as among the most bizarre in rock history. The band members and their wives were backstage at a show in Cleveland when Elyssa Perry and Hamilton’s wife, Terry, got into a scuffle. When Elyssa threw a glass of milk at the other woman, the rest of the band got into a shouting match that didn’t end until Joe Perry said he was quitting (not long after, Whitford followed him out the door).

Perry wouldn’t return for four years. What he and Tyler discovered during that separation was that they needed each other. Though Perry had started his own band, the Joe Perry Project, none of the three albums he released in quick succession reached anywhere near the levels of critical and commercial success Aerosmith had enjoyed. And though Tyler had kept Aerosmith going with two replacement guitarists, the two albums he finished without Perry, Night in the Ruts and Rock in a Hard Place, turned out to be complete flops.

By the early 1980s, Tyler and Perry were still making money from song royalties, but Aerosmith’s brand of music had fallen out of favor, which meant neither man was making enough to support his epic drug habit. Tyler lost his Porsche, his private jet, and his house. Perry, who divorced Elyssa, was several million dollars in debt and in trouble with the IRS. Near bankrupt, Tyler lived in a decrepit New York hotel on the $20 a day his manager gave him. Perry slept on the couch of his new manager, Tim Collins, who also paid several months of his child support.

Tyler tried to put on a brave face. Perry wasn’t “missed except in the hearts of die-hard fans,” he said three years into the breakup. “He thought he had a lot more to do with the band than he really did.” Meanwhile, though, it was impossible to ignore that Tyler was dressing up Perry’s replacement, Jimmy Crespo, to look like, well, Joe Perry. Rick Dufay, Whitford’s replacement, noticed a measure of heartsickness in the lead singer. The music aside, Tyler deeply missed Perry; he didn’t feel like the same person without him. “On some level,” says a former manager, “Steven is always torn between feeling like ‘I don’t need these guys’ and not wanting to lose Joe. I think it’s a deeper, more emotional thing than songwriting chemistry.”

On Valentine’s Day 1984, Perry went to see an Aerosmith show for the first time since quitting. He visited with Tyler backstage, and they started the process of rebuilding their relationship. “They realized the tension between them is what serves them,” says Tim Collins, who began representing the whole band when it reunited. “Steven knows it, so does Joe, but they don’t want to know it.”

Yet even amid the reconciliation, the band couldn’t let go of past slights. If ever there were a moment that encapsulated Aerosmith’s complicated history — the resentments and the passion — it was during a show in Springfield, Illinois, on the first night of the “Back in the Saddle” comeback tour. First, Tyler got so drunk he fell off the stage. Then, after he hauled himself back up, he got into a brawl…with the other members of the band. The fans went wild.

With a taste of what the group could accomplish when it was firing on all cylinders, Tyler finally agreed to go to rehab (over the next several years, his four bandmates also got clean). The run of success that followed is widely considered the greatest comeback in the annals of rock history: A remake of “Walk This Way,” in collaboration with Run DMC, helped pull rap into the mainstream — and made Aerosmith seem cool again. Albums like Permanent Vacation, Pump, and Get a Grip won over an entirely new generation of fans. “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” from the Armageddon soundtrack, became the first single of their career to top the Billboard chart. In 2001, the band was awarded a prize that amounts to the American equivalent of knighthood: playing the halftime show of the Super Bowl. That same year, they released an album, and were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, where they were feted as “the greatest rock band in American history.”

Throughout its career, Aerosmith had been called America’s answer to the Rolling Stones. In the early days, it was a sarcastic comparison. Now it was true.

Even at the pinnacle of its success, Aerosmith just barely managed to hang together. Though they would release several albums over the next few years, they created little new material (with good reason: Tyler and Perry stopped writing songs together around 2000). The band recorded an album of blues covers, Honkin’ on Bobo, that surely pleased Perry, who prefers old-school rock ’n’ roll, but was perhaps less popular with Tyler, whose musical tastes run toward sleek pop ballads. Without an album of fresh songs, Aerosmith saw its concert venues get progressively smaller and its opening acts get older. The 2009 tour was to feature ZZ Top, who hadn’t had a hit song in 25 years.

When Tyler began behaving oddly again, a year or so ago, Perry revived the Joe Perry Project for the first time in more than two decades. After Tyler fell off the stage in South Dakota in August, and Aerosmith canceled the rest of the tour, Perry took his solo show on the road. He was staying busy, to be sure, but it also looked as if he were trying to prove he didn’t need to sit around and wait for Tyler’s return.

While drumming up publicity for his tour, Perry began suggesting to reporters that Aerosmith might go on without Tyler. He said he was auditioning singers to replace him, at least temporarily. On November 9, 2009, he posted a message to his Twitter feed: “Aerosmith is positively looking for a new singer to work with.” Knowing Tyler’s jealous streak, Perry shouldn’t have been surprised when he turned up backstage the next night at the Fillmore, a 1,200-person venue in Manhattan, where the Joe Perry Project was playing. Tyler hadn’t said he was coming — he simply bought a ticket at the door — but he wondered if he could sit in on the band’s encore. “Being an acquaintance of 40 years, I said, ‘Why not?’” Perry recalled when recounting the story, making an obvious effort to avoid using the word “friend.”

Whether it’s his show or not, Tyler always likes to be the boss. And when he got up onstage, he grabbed a microphone and said, “New York, I want you to know: I am not leaving Aerosmith.” The crowd went nuts. Tyler wasn’t done. He turned to the guitarist: “Joe Perry, you are a man of many colors. But I, motherfucker, am the rainbow.” Perry was about to respond when Tyler cut him off with a signal to the drummer, and Perry’s band launched into the opening notes of “Walk This Way.”

There are two things that stand out about the episode. The first is how comfortable Tyler looked onstage, especially compared with the stilted, self-conscious posing of Perry’s lead singer, a 30-year-old German named Hagen Grohe, whom Perry’s second wife, Billie, discovered on YouTube. The fact that Tyler, now 62, can somehow still make something as ridiculous as ripping his shirt open look cool shows why he is a superstar and almost everyone else in the world isn’t. The second point is that Tyler looked as if he were, to put it delicately, less than completely sober (which makes the first point even more impressive). He mumbled through some of the song’s lyrics, and apparently forgot others altogether. At the end, he even improvised a new line: “I just wanna get high. I-I-I-I just wanna get high.”

Unsurprisingly, Tyler admitted a few weeks later that he was still addicted to prescription painkillers. Just before Christmas, he checked himself into a detox program, reportedly at the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, California. In a statement, he promised he’d return to the band after getting clean. “I love Aerosmith,” he said. “I love performing as the lead singer in Aerosmith.”

After completing the intensive first month of treatment, Tyler was allowed to come and go from the center’s grounds as he pleased. One night he stopped into karaoke night at a sports bar called the Tilted Kilt, named for the short plaid skirts worn by the waitresses. Tyler obviously wasn’t drinking that night, and a member of his entourage told the karaoke emcee, a DJ named Mike May, that he wouldn’t be singing, either. Yet when May looked over to Tyler’s table during “Like a Rolling Stone,” he saw him singing along with the chorus. A little later, when two guys were about to get booed offstage for butchering “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” Tyler jumped in and rescued the song.

Photograph by Chris Walter/Wire Image/Getty Images

Then things got really weird. Shopping at a Home Depot a few days later, Tyler talked an employee into letting him sing a couple of songs over the PA system. A hit off the store’s helium tank gave him a little help with the high notes.

Tyler’s odd behavior became monologue fodder for late-night hosts — Jimmy Kimmel joked that he’d be singing “Caulk This Way” on his upcoming Home Depot tour — but there was at least one person who found little about the impromptu performances funny: Joe Perry. “Anybody that’s willing to go out there with a fuckin’ red ball on their nose usually tends to get the attention, and, you know, that’s what he chooses to do,” he said. “I just look at it and I go, ‘What the fuck is he doing?’”

That’s more or less what went through Mike May’s mind at the Tilted Kilt, too, at least at first. But then he remembered what the singer had told him during a moment away from his handlers: “I need to do this,” Tyler had said, gesturing to the karaoke machine. He wanted to come in late at night, though, when the place was closed. Could that be arranged? May realized that Tyler didn’t need to perform as much as he simply needed to sing. “It’s like he was in singing withdrawal,” May says.

While Tyler was still in California, Perry continued to talk about replacing him. He would eventually float (or endorse) more than a half-dozen options, including Paul Rodgers, the singer who fronted Queen after Freddie Mercury died, and Sammy Hagar, who took over vocals for Van Halen after David Lee Roth quit. On the business side of the band, Tyler was under additional pressure. During a January meeting between Tyler’s manager, Allen Kovac, and Aerosmith’s, Howard Kaufman, the latter reportedly said Tyler should leave the band — that the group would be better off without him.

Few people who really understand how Aerosmith operates believed that the band would follow through on the threats it was making in the press. “It’s one thing to replace Brad, or even Joe Perry, but Steven is the one person they can’t replace. You couldn’t have Aerosmith without him,” says a former band insider. “I felt like that was entirely kind of a public shakedown — ‘Okay, if you don’t come back we’re going on without you.’”

As transparent as the ruse may have looked, it’s important to realize that Joe Perry knows Steven Tyler better than any other person on earth, and he understood one fundamental truth about Aerosmith, and Tyler’s place in it: The one person who could kill the band — the one who is truly essential to its identity — also happens to be the one who could never let it die. Tyler doesn’t need it for the money: As a songwriter, he recently sold a stake in the Aerosmith catalog he owns for $50 million. And he doesn’t need it for the fame. But he does need it. Perry knows, and has always known, that Tyler lives and dies by Aerosmith. “I still remember Steven saying to his last wife, just before they walked down the aisle, ‘You know I love you, but the band comes first,’” says Collins, the former manager.

Whenever anyone has threatened to break up the Aerosmith family, Tyler has been the one to bring them in line. The time Perry said he was going to join Alice Cooper’s band, Tyler immediately contacted him. When Kramer was about to join a new group, Tyler called him back to the studio to cut the next Aerosmith album. Maybe it was a coincidence, but when Perry said he was “definitely” looking for a new singer, Tyler showed up to reassert himself the very next night. This time, he had his lawyer send the band a stern letter that said he would sue to stop them from kicking him out.

Tyler considers himself both the progenitor and protector of Aerosmith, and, as such, he’s never been able to understand why anyone would ever doubt his commitment to it. He never believed his own side projects posed a threat, even while he constantly felt threatened by those belonging to the other members. “He’s your typical American alpha male,” says a former band insider. “He wants to fuck who he wants to fuck, but he doesn’t want his wife to cheat.”

In February, at Tyler’s request, the group convened at their rehearsal space in Massachusetts. It was the first time they’d all been together anywhere besides a stage for months. Everyone, as Hamilton put it, was “lawyered up” with their own representatives, and all aired their various grievances. If past history is any indication, they didn’t exactly settle their old resentments, but they were in the same room. That was a start. Aerosmith’s biggest problems come when the band members ignore one another. As long as they’ve been able to talk — and fight — they’ve always managed to reach an uneasy détente.

They did at least hash out one thing: Tyler agreed to head out on that tour of South America, the one he had said no to back in Hawaii. “It’s sort of like a marriage: You’ve got to make concessions to keep everybody happy,” says Tabano, the former guitarist. “I think they realize that today.”

Not long after the meeting, Kramer took to Twitter with the following message: “Aerosmith is back!”

On February 24, 2010, the band put a video on their website announcing the new tour. In it, they’re sitting in a recording studio: Tyler is in the middle, with Perry, Hamilton, and Kramer around him (Whitford was traveling). The opening guitar riff of “Back in the Saddle” plays in the background.

“We’re Aerosmith, and you know what, the rumors are true,” Perry says, adding, “I think.” Tyler looks at him. “You think?”

If there were a script for the reunion announcement, this is where Tyler strayed from it. “I just auditioned and I got the gig,” he says. Taken by surprise, Hamilton and Kramer laugh nervously. Even the usually stoic Perry allows himself a half smile. “We’re coming your way and rockin’ your world. Look out, baby, ’cause here we come again.”

After the Aerosmith logo flashes on the screen, the video cuts back to the band. Tyler is pointing at Perry and grinning widely, as if he’s looking for the guitarist’s approval; Perry is ignoring him, texting something on his phone. You can just tell that any day now, they’ll be at each other’s throats. And when that day comes, everything with Aerosmith will again be exactly as it should be.