Safe Harbor?

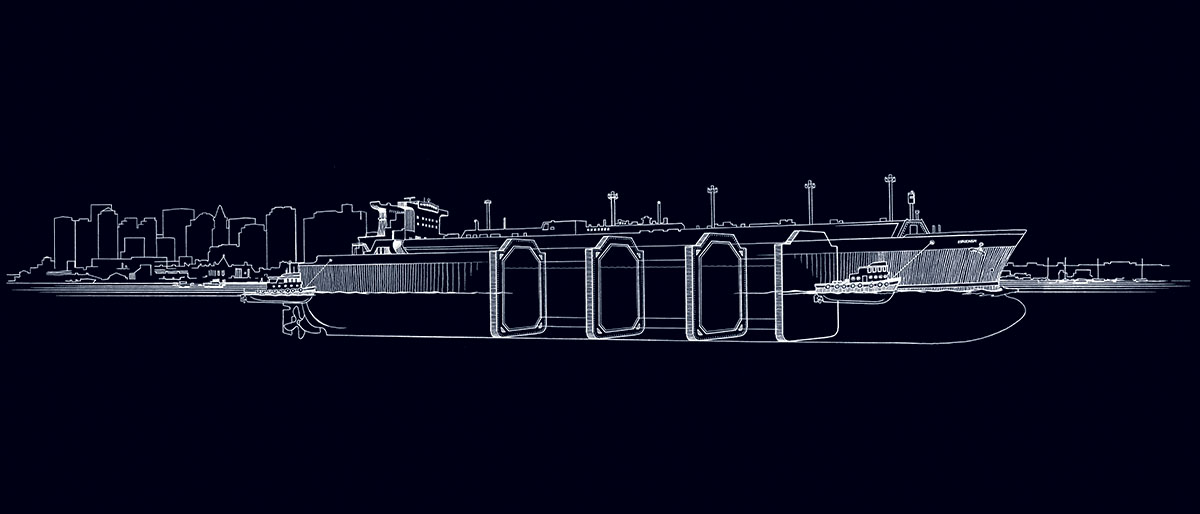

At 2:30 a.m. on a Tuesday in May, a 53-foot pilot boat called the Mystic motored out to just beyond Boston Harbor and came alongside the GDF Suez Neptune. Like all ships entering the harbor, the Neptune — 928 feet long and 141 feet wide — required a licensed Boston Harbor pilot on the bridge, and Frank Morton was on the job. Stepping to the edge of the Mystic’s bow, he reached for the rope ladder that dangled from the Neptune like something on a pirate ship, then clambered up the side and onto the state-of-the-art tanker.

As he directed the ship into the harbor, blue lights whirred in every direction: on law-enforcement escort boats, on police cruisers parked at the end of nearly every pier. A chopper hovered as the tanker sailed past the airport, past downtown, and up the Mystic River. The security detail was a spectacular acknowledgment of the ship’s cargo: 38 million gallons of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, enough fuel to power a region or, in the wrong hands and under the right conditions, incinerate half a city.

LNG tankers have been controversial ever since they started steaming through Boston Harbor to port in Everett in 1971, but became even more so after 9/11. If terrorists caused even 10 percent of the typical LNG tanker’s payload to spill and ignite, the resulting fire could be calamitous, according to a 2004 report by Sandia National Laboratories for the U.S. Department of Energy. The study didn’t publicly estimate casualties for Boston; in fact, no study has since 1977, when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission estimated that up to 3,000 would die. Today, when the city’s population of 610,000 swells to more than one million on workdays, the number could be higher. It’s not hard to imagine why Boston remains the country’s only major city with an LNG terminal.

The tankers were such cause for concern after 9/11, Mayor Thomas Menino asked a federal judge to ban them from the city. The effort failed, and the LNG debate faded — until this past February, when shipments started arriving from Yemen, a known terrorist haven and site of the 2000 attack on the USS Cole. “This is serious stuff,” Menino says. “I take it very seriously, and my public-safety officials take it very seriously. We don’t have the equipment to put down an explosion of an LNG tank. They say, ‘Well, it will never happen.’ Well, 9/11 hadn’t happened either. We live in a different era.”

For nearly a decade, Menino has been urging the federal government to develop more natural-gas pipelines and offshore LNG terminals for New England — an expensive solution to what has been, so far, a hypothetical problem. Executives of Distrigas, a subsidiary of French conglomerate GDF Suez, which owns the Everett terminal, counter that security is better than ever, and point to their industry’s sterling safety record: There hasn’t been a serious incident since an LNG storage tank exploded in Cleveland in 1944, destroying 79 homes and two factories, and killing 130 people.

Still, even ships coming from countries more stable than Yemen are scrutinized. The Neptune, for instance, had sailed from Trinidad. Just before dawn it reached Everett safely, like the nearly 1,000 ships before it.

Yet some LNG experts, like University of Arkansas chemical engineering professor Jerry Havens, point out that something need go wrong only once. “Moving this much flammable fuel through a populated area should be considered…low risk, low probability, but high consequence,” he says.

LNG 101

What is LNG?

Natural gas that’s been turned to liquid by chilling it to negative 260 degrees Fahrenheit. As a liquid, the gas occupies 600 times less space, making it easier to

ship. In addition to coal and oil, natural gas is one of the world’s most prized fossil fuels and is found in large deposits in North America, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia.

Why is natural gas important?

Besides firing up your stove, natural gas heats about half the homes in Massachusetts and generates 40 percent of New England’s electricity.

Why do we import LNG?

North America has plenty of natural gas, but not enough New England pipeline. The LNG that comes into Everett provides 20 percent of the region’s annual supply — double on the coldest days, when demand spikes. The Mystic power station, next to the Everett terminal, runs on LNG and fuels 30 percent of Greater Boston’s power supply.

Where do the shipments originate?

Yemen, Egypt, and Trinidad. Distrigas declined to give exact numbers, but Frank Katulak, president and COO, says he’ll get about 60 shipments a year: 10 from Yemen, 5 to 7 from Egypt, and the rest from Trinidad.

Why is Boston the only major city with an LNG terminal?

Because nobody else wants one. When the Everett terminal was built in 1971, many viewed it as a step toward the future — an important energy source at the hub of a region. Since then, environmental and security concerns have scared off other cities, including Providence and Long Beach, California. Offshore LNG facilities are more palatable to many critics (we have two terminals off the New England coast), but they’re not as convenient as land-based terminals because they can’t directly fuel power plants.

Why do we import from Yemen now?

Until February, Distrigas received all its shipments from Trinidad, but relatively low U.S. natural-gas prices caused some Trinidadian suppliers to seek out customers willing to pay more, Katulak says. To replace inventory, in 2005 Distrigas signed a 20-year deal to begin importing LNG from Yemen.

Who’s on the ships from Yemen?

Distrigas is using the same ships and crews it’s always used, and has hired no Yemeni nationals, Katulak says. Some critics have warned about the possibility of stowaways. Former U.S. counterterrorism chief Richard Clarke asserted in his 2004 book, Against All Enemies, that Al Qaeda stowaways had infiltrated Boston via LNG tankers from Algeria, a claim the FBI disputes. Katulak rejects the stowaway concern, arguing that it would be extremely difficult for someone to hide undetected on a ship for 18 days. Today, even Clarke is less concerned than before about stowaways. “There are easier ways” to get into the country, he says.

Shouldn’t the 1977 risk-assessment study be updated?

Yes. Boston Deputy Fire Chief Jay Fleming has been agitating for this type of update for years. Menino says the Department of Homeland Security in February promised him an assessment of how to get LNG out of the harbor, but has yet to deliver a report. The DHS declined to comment.

How would the city respond to an LNG fire?

The worst kind of fire would be an event so large and unprecedented, it’s near impossible to prepare for. The Massachusetts Firefighting Academy in Stow has an LNG training program, but it focuses on fighting fires from smaller-scale leaks, such as from pipelines or transport trucks. Pool fires (see page 91) are just too big. “We’re not training for that type of an incident,” says State Fire Marshal Stephen Coan, “and I don’t think that you can train for that type of an incident” on a large scale. Still, Boston city officials, Distrigas, and the Coast Guard say they regularly collaborate on joint emergency drills.

What does Menino want?

The mayor wants tankers to stop coming, which would happen only if the region found other ways to get natural gas: via offshore facilities, for instance, or more pipeline, says Donald McGough, director of the city’s Office of Emergency Preparedness. City officials have said each shipment costs $25,000 in public-safety measures.

THE ROUTE

Every LNG tanker cruises past the piers and bridges of downtown and Charlestown before docking in Everett. Here are some of the security measures taken along the way:

Four days out

The LNG tanker is required to alert the Coast Guard of its approach and provide a manifest. The Coast Guard runs background checks on the crew. (Distrigas performs its own background checks before its ships sail.) The tanker must contact the Coast Guard again at 48, 24, 12, and 5 hours outside Boston Harbor.

Six to twelve miles out

Two Coast Guard officers board the tanker for safety checks and to watch for vessels that get within 500 yards. The Coast Guard also sends in teams of 12 to 24 officers for random security sweeps, though they’re more likely to spot check

ships from Yemen.

Five miles out

A member of the Boston Harbor Pilot Association meets and boards the tanker. After safety and information protocols are performed, the pilot directs the ship toward the harbor at about 10 knots, or 12 miles per hour.

Entering Boston Harbor

When the ship enters the North Channel, that’s the point of no return. Until then, the harbor pilot can decide to stop, no questions asked. From here, though, the pilot has committed. As the ship passes through the harbor, it hugs the East Boston shoreline, where the channel is deeper. The Coast Guard allows LNG tankers to enter only on clear days.

Pleasure Bay

As the ship slows, four tugboats lash themselves to its sides. (The tugs can haul the tanker and help it maneuver in case of emergency.) Here, the tanker enters the security zone, and law enforcement appears. No unauthorized vessels are allowed within 500 yards. At least five small boats — the Coast Guard, city and state police, and Massachusetts Environmental Police among them — escort the tanker. One or more choppers hovers above.

HOW DANGEROUS IS IT? THE REALITY

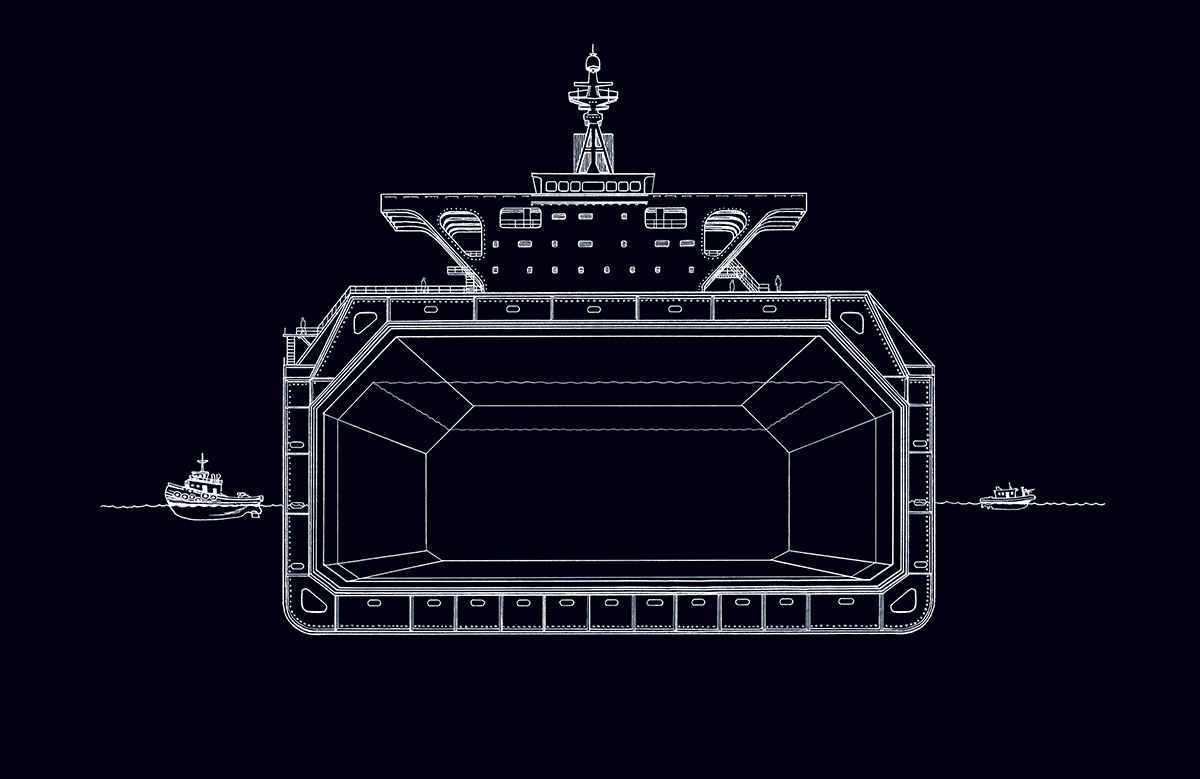

Can LNG catch fire inside the tanker?

LNG itself is not flammable. You could light a match, drop it into a vat of the stuff, and be perfectly fine. Yet if LNG, which is extremely cold, spills out onto the relatively warm ground or water, it immediately starts to evaporate. That forms a vapor, which is flammable, but only under certain conditions (see “The Fire”). LNG tankers are built with double hulls, each made of one-inch-thick steel. By contrast, the USS Cole had a single hull of half-inch-thick steel.

Would it be easy to blow up a tanker?

Successfully attacking an LNG tanker would be very difficult, experts say, but it’s hard to say exactly how difficult. For most ships passing through Boston, an attacker coming from outside the ship would first have to breach the security

zone, then cause a leak by blasting through about 30 feet of the ship. Sandia considered all conceivable means and methods of attack for its 2004 report, though that part remains classified. “We got drawings of the ships and did very high-definition structural calculations of the damage you would get from those types of credible threats,” says Mike Hightower, one of the study’s authors. “We [considered] things like an attack, a hijacking, an insider threat where a member of the crew…brought some explosives onboard. We looked at a range of weapons, and we looked at things people could make into weapons: small aircrafts, small boats.”

Do LNG accidents happen often?

There hasn’t been a major LNG incident since the 1944 storage-tank explosion in Cleveland. And a shipwreck doesn’t automatically mean disaster: A tanker once hit a rock outcropping head-on in the Strait of Gibraltar and had to be towed to port, yet lost not a drop of LNG.

EXPERTS SAY…

LNG ships carry four to six tanks. If about half of a single 6.6-million-gallon tank spilled from a 54-square-foot hole and the vapors ignited, the fire would “cause significant damage to structures, equipment, and machinery” within a 1,280-foot radius and leave second-degree burns on people more than three-quarters of a mile away, according to Sandia’s study, which measured impact on open water. In a city, variables such as buildings would affect the fire’s path and intensity. Sandia’s worst-case scenario measured the result of LNG spilling simultaneously from three tanks, which “would set structures aflame out to 2,067 feet and burn people as far as [1.3 miles] away,” says study coauthor Mike Hightower. Sandia is now studying scenarios in which tanks are breached successively. Results are expected this summer.

THE FIRE

1. LNG immediately begins to evaporate when it spills. A vapor cloud forms and grows, and you hope there’s no spark. Even with a spark, only the cloud’s edges, where 5 to 15 percent of the air is LNG, can ignite. Yet if that part catches fire, the whole thing burns.

2. In an attack, a spark would probably be present as the LNG began to spill, so a fire would start right away. Because the LNG hits the water faster than it all can evaporate, it would form a pool on top of the water. As more spilled, the pool — and the fire — would grow.

3. The LNG would continue feeding the blaze (imagine the fire being attached to the pool) until all the fuel evaporated and burned off, which could take anywhere from three to forty minutes. By then, anything within reach could have ignited and set off other fires.