Teenage Wasteland

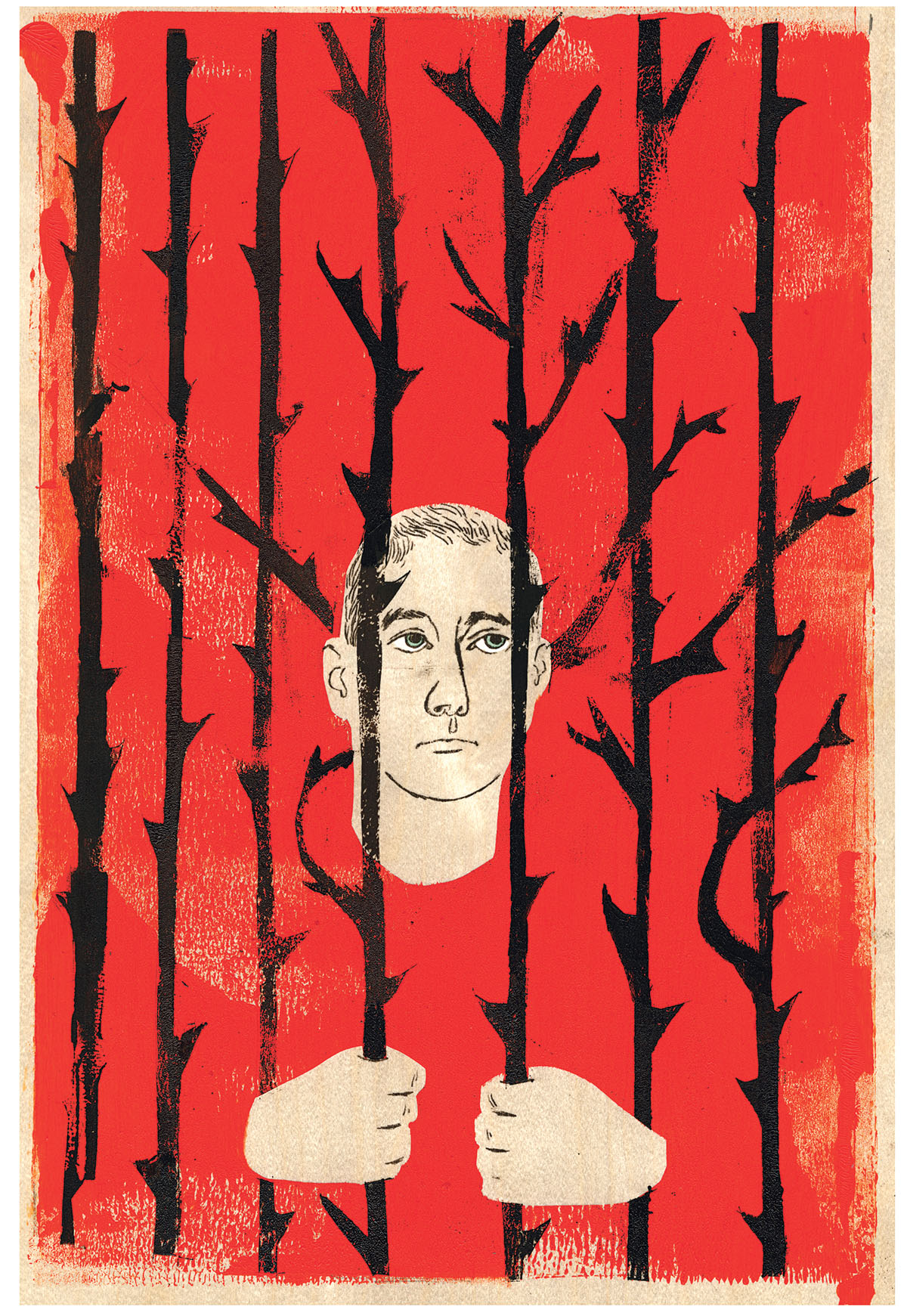

ILLUSTRATION BY EDEL RODRIGUEZ

What if Phoebe Prince had brought a knife to school? What if she had turned her despair on a classmate instead of on herself? What if the 15-year-old had not killed herself but had stabbed to death a girl she had never met in a school bathroom?

We wouldn’t be talking about anti-bullying laws and mean girls. We would be talking about school security and about life in prison without parole. We would be talking about John Odgren.

Their cases could not be less alike, we tell ourselves. Phoebe Prince was a victim, an innocent girl who hanged herself last January after being tormented by bullies. John Odgren was a cold-blooded killer convicted in April of stabbing to death a classmate he didn’t even know.

But how different were these two, really? Phoebe committed suicide after months of harassment. John committed homicide after years of ostracism. Phoebe’s mother could not persuade school officials to intervene in the bullying of her daughter. John’s parents could not persuade school officials to approve a more appropriate setting for their mentally ill son. And yet, the despondency and impaired judgment that led Phoebe to take her life elicits our compassion; the depression and distorted thinking that led John to kill another student triggers our contempt. In matters of juvenile justice, we prefer the clarity of black and white, villain and victim, even when the reality is much more ambiguous. It is so much easier to arrest a few South Hadley bullies and to lock up a mentally ill killer than it is to confront the systemic failures that produced them.

When he was convicted of first-degree murder in April, John Odgren became the 58th juvenile sentenced to life without parole in Massachusetts since 1996. That’s when a draconian revision of state law put children age 14 and older accused of murder beyond the reach of the juvenile justice system. Just as we are now told that bullies are more numerous and more deadly than the schoolyard thugs of old, we were warned then that juvenile killers were multiplying, morphing into remorseless “super-predators” whose youth was irrelevant to the magnitude of their crimes.

No matter the circumstances, a juvenile charged with first-degree murder in Massachusetts must be tried as an adult. If convicted, he or she must be sentenced to a prison term of life without parole.

Odgren was 16 on January 19, 2007, when he stabbed to death 15-year-old James F. Alenson of Sudbury. For years Odgren had taken medication for symptoms of depression, anxiety, ADHD, and Asperger’s syndrome. A special-needs student from rural Princeton, he had been in Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School’s Great Opportunities program for only a few months. It was his fourth out-of-district placement in four years.

His parents knew a large public school was the wrong setting. “He was all set to go to a smaller [school] and then, at the end of August, we were told the school was not approved,” says his mother, Dorothy Odgren, a nurse. “We fought the placement, but there is a money issue here for towns…. We asked for him to have a one-to-one aide to help handle the transition to such a big school. We were told, ‘That will only attract more attention to him and you want him to blend in.’ No, what we wanted was for him to have the attention he needed. He was never going to blend in.”

How could he? He wore a fedora in class. He said whatever random thoughts flashed through his racing mind. His obsession with horror stories coexisted with a preoccupation with butterflies and astronomy. The compulsion to ramble about such shifting, disconnected fixations is a feature of Asperger’s, and exacerbates the social isolation of students struggling with the condition. In John’s case, blurting out his every thought meant an end to birthday-party invitations by the second grade.

In that fatal moment in a boys’ bathroom, John Odgren was in the grip of a delusion that he was a character in The Dark Tower, a series of Stephen King novels that had lately dictated his mode of dress and uncharacteristic verbal swagger. He did not know his victim. He had no rational motive to kill him. But, without a finding of legal insanity, he was as guilty of first-degree murder as any career criminal.

Prosecutorial discretion is an oxymoron in cases like these. It is the rare district attorney who can overlook public fear and fury in the wake of homicide in a public school and seek an indictment on a lesser charge. Middlesex District Attorney Gerry Leone never considered any option but first-degree murder. He did not buy Odgren’s insanity defense. He did not think the boy’s mental health issues or his long history of being bullied – his first of many suicide threats came at age eight, and his only prior acts of aggression were in response to bullying – were mitigating factors in the crime. Under our adversarial system, the prosecutor speaks for the victim, in this case a blameless kid who suffered a painful, violent death because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Leone would have been pilloried had he acknowledged any shades of gray.

What is our excuse?

“It isn’t easy to see someone who has taken another’s life in such a brutal way as a sympathetic character,” Paul Odgren, a researcher in cell biology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, says of his son. “It is possible, though, to see that this is not a simple case without in any way minimizing the horrific loss the Alenson family has suffered. We certainly don’t minimize it. For two and a half years we drove to Cambridge [where John was incarcerated awaiting trial] and passed Emerson Hospital. Every day, I was conscious that that is where the Alensons had to go to identify their son’s body. We sat not 10 feet from them for a month in the courtroom. We know the pain they are in.”

The Odgrens know the pain John is in, as well. “We have spent his life trying to get John the help he needs,” says his father. The special education John needed was too expensive for his school district, though the state will spend about $2.5 million to imprison him for the rest of his life.

That cost estimate comes from the Children’s Law Center of Massachusetts, which last September released the first comprehensive study of life without parole for juveniles in the state.

The opportunity, not the certainty, of parole for juveniles convicted of murder is at the heart of the CLCM’s recommendation that such life sentences be eligible for review after 15 years. That approach would satisfy society’s demand for accountability and punishment but leave open the possibility that a child can change.

The proposal acknowledges advances in neuroscience documenting what every parent knows instinctively: that adolescent brains have not matured, that the prefrontal cortex, which regulates impulse control, has not fully developed in teenagers. There is a reason, after all, that we don’t let adolescents sign contracts, buy cigarettes, vote, serve on juries, or even get tattoos without our permission.

In the year since the CLCM released its report, several states have amended their laws to reflect this new understanding of brain development. Governor Deval Patrick and the Massachusetts legislature, on the other hand, have ignored the issue while countenancing, with their silence, the sentencing of a transparently mentally ill teenager to life behind bars. Toothless anti-bullying bills are an easier sell in an election year.

The political cowardice is especially striking because Patrick has put the very people in place who could address the issue. Jane E. Tewksbury, his commissioner of the Department of Youth Services, cofounded Citizens for Juvenile Justice in 1994 to oppose the regressive policies of Governor William F. Weld. Gail Garinger, former first justice of the Middlesex Juvenile Court, is now head of the Office of the Child Advocate. Patrick created the position with much fanfare in 2007, but it’s since been underfunded and largely ignored.

Even as Massachusetts sits idle, the U.S. Supreme Court is upending the harsh juvenile sentencing practices that swept through the states in the late 1990s amid the frenzy about “super-predators” who never did materialize. (Juvenile crime has declined steadily in the very period we were warned it would escalate.) Five years ago, in Roper v. Simmons, the high court ruled that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit the death penalty for minors because juveniles, in the court’s words, are “categorically less culpable” and more amenable to rehabilitation than adults. “The reality that juveniles still struggle to define their identity means it is less supportable to conclude that even a heinous crime committed by a juvenile is evidence of irretrievably depraved character,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote. “From a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”

Weeks after John Odgren heard his life sentence and handed his mother his stuffed bunny Nicholas, which he had used to comfort himself in the holding cell during his trial, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment also applies to life sentences without parole for juveniles in non-homicide cases. “A State need not guarantee the offender eventual release, but if it imposes the sentence of life, it must provide him or her with some realistic opportunity to obtain release before the end of that term,” Justice Kennedy wrote in Graham v. Florida. “Life without parole is an especially harsh punishment for a juvenile,” he added.

Is it not as harsh for a juvenile who kills while in the grip of mental illness?

Odgren is luckier than most such defendants. He’s white, and from a loving, middle-class family able to hire Jonathan Shapiro, one of the best defense lawyers in the state. The Children’s Law Center reviewed the cases of 46 of the 57 other inmates serving life without parole for crimes committed as juveniles. The racial disparity is stark. Blacks make up 6.5 percent of children in Massachusetts under age 18, but 47 percent of those sentenced to life without parole.

Like John Odgren, 41 percent of the inmates whose cases the CLCM reviewed had no prior criminal record. Twenty percent of the 42 inmates interviewed participated in a felony in which someone was killed, but not by the teenager.

In a concurring opinion in Graham, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote, “Society changes. Knowledge accumulates. We learn, sometimes, from our mistakes. Punishments that did not seem cruel and unusual at one time may, in the light of reason and experience, be found cruel and unusual at a later time.”

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court will eventually review the Odgren case, as it does all first-degree murder convictions. Prosecutors, meanwhile, voiced no objections a few weeks ago when a judge extended John Odgren’s commitment to Bridgewater State Hospital by six months. The court found prison to be an inappropriate placement for him, given his need for psychiatric care.