Admissions of Guilt?

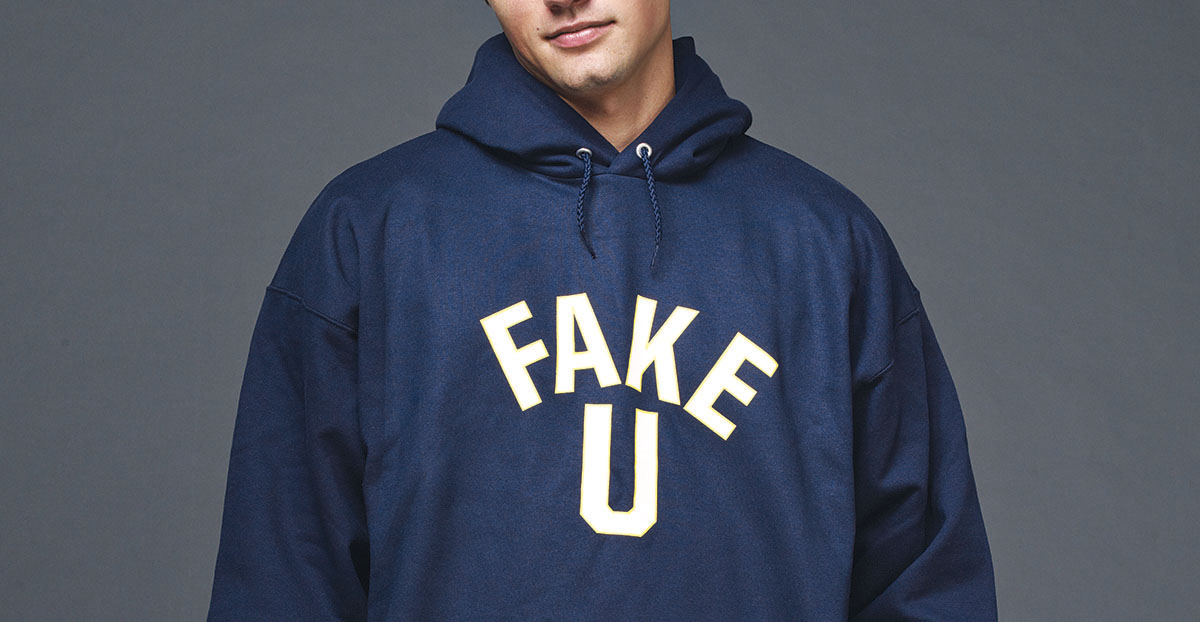

PHOTO BY DAVID YELLEN

Jim McFadden was bored, mostly, when he came up with the idea. It was a rainy afternoon during Harvard’s senior week, the days before graduation when “there’s no work left to do.” His mom called. The top story on the local news back home in Olmsted Falls, Ohio, was about Adam Wheeler, a classmate of McFadden’s who had been charged with faking his way through Harvard. That’s when McFadden knew the Wheeler story had gone big and that, like every juicy controversy, the matter deserved one thing: a T-shirt.

McFadden’s “Free Adam Wheeler” tees — which featured Wheeler’s mug shot on the front and his fake résumé on the back — were an instant hit. Donning their sartorial support of Wheeler at the senior talent show last May, McFadden and his friends fielded compliments, high-fives, and several requests to purchase. “It wasn’t a roaring business by any means,” says McFadden. “We didn’t even want to make a profit, just to break even and get people laughing.” Which they did. “To be honest,” he says, “we didn’t see what the big deal was.”

It may seem unusual that Wheeler ultimately became a source of amusement for students who’ve spent the past four years striving for a degree from one of the most hard-driving institutions in the world. Wasn’t he the guy who had made a national mockery of their soon-to-be alma mater?

But to some Harvard students, the media sensation that followed Wheeler’s arrest was baffling. After all, who doesn’t game the system?

For centuries, Harvard has been regarded as the pinnacle of academic achievement, a place where raging ambition meets endless opportunity. This year the College received a record 30,489 applicants for the 2,110 spots in the class of 2014. For those select students who can have their pick of any college, Harvard often triumphs for one reason: It’s Harvard.

Historically, the school has been criticized for representing the extreme end of the sort of exclusivity inherent in college admissions: crawling with well-off white kids. In his book Privilege: Harvard and the Education of the Ruling Class, Ross Douthat, a 2002 graduate and New York Times columnist, argued that Harvard is a pit stop for shamelessly determined, entitled social climbers who want maximum success with the least amount of effort; that, like Gucci or Chanel, Harvard is simply a luxury brand, a nameplate that often overshadows its substance.

But today’s Harvard is quite different from the long-standing caricature. For many, in fact, the school has become more accessible than ever, thanks to admissions and financial aid reforms implemented in recent years (including generous need-based scholarships and the termination of early admissions, long seen as an easy entry for legacies and wealthy applicants). Though average yearly tuition — including room, board, and fees — for 2010 to 2011 topped $50,000, the average financial aid package was just over $40,000, and about 70 percent of students received some form of aid.

Once inside, students tend to do well, and not just because they’re smart. Grade inflation has long been a problem; a 2007 report released by Harvard’s dean of the College revealed that more than half of the school’s grades were in the A range. Ninety-seven percent of Harvard students graduate; by contrast, at MIT, graduation rates hover at around 90 percent. “Harvard was more manageable than I thought it would be,” says Benjamin Kultgen (’08), who transferred from Tufts as a junior. To stand out, students tend to focus on advanced means of competition, from seeking leadership in social clubs and extracurriculars to garnering academic prizes.

In the case of Wheeler, prosecutors say, the desire to belong among the best and brightest began with extensively misrepresenting himself on his application and culminated in compulsive plagiarism of class papers, honors projects, and even parts of his application for the heavily vetted Rhodes and Fulbright scholarships. “People are accepted [at Harvard] because they are the best of the best, and nothing else,” wrote Douthat, who once used the word “pathological” to describe Harvard. “In the Harvardian universe, then, the advantage often goes — at least in the short term — to the manipulative and dishonest and cutthroat, the people willing to backstab and lie and cheat their way upwards.”

Some students disagree. “I think we can assume that not a lot of people plagiarize or fake transcripts to get into elite universities,” says Kultgen. “In my experience, plagiarism was unheard of at Harvard…. If you’re at a place like Harvard, you’re already ahead. Why jeopardize that?”

Kultgen knew Wheeler. He led the orientation group for transfer students that Wheeler was a part of, and describes the former student as smart and quiet. “He quickly made friends,” Kultgen says. “There was no suspicion that his credentials were dubious.”

McFadden says Harvard’s honors policy is drilled into students from day one, and that faculty display high levels of trust and respect for students — a trust that, perhaps, too often assumes the best of students. “The school places integrity and excellence above all,” he says. “As such, there wouldn’t seem to be a need for strict skepticism of excellent student achievement…. I would be more afraid to plagiarize a Harvard paper than to be caught doing drugs.”

Even if everything said about Wheeler is true, he’s hardly Harvard’s first con. Esther Reed was a teenage runaway and gifted chess player when, in 2002, she assumed a fake identity in order to enroll at Harvard, from which she accepted more than $100,000 in financial aid. (Reed is currently serving four years in prison.) And in 1999 Harvard Extension School student Edward Meinert pretended to be a College undergrad so he could join myriad organizations, rush fraternities, and take advantage of other networking opportunities exclusively limited to College students.

“Who doesn’t want to be a Harvard graduate in this day and age when credentials equal financial success?” says David Callahan, an Ivy League graduate and author of The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead. “We live in an incredibly status-oriented society, and there are major economic and social rewards for having the highest credentials. And you don’t get much higher in terms of educational credentials than going to Harvard. The difference between going to Harvard University and Boston University could translate into hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars in difference in lifetime earnings…. So at some level, it should be no surprise that people fake their credentials.”

Admissions experts agree that nearly all college applications contain elements of untruth — whether it’s exaggerated extracurriculars or professionally polished essays — and that it’s impossible to fact-check every claim. “There is embellishment in a disturbingly large number of applications — as many, perhaps, as 5 percent,” says Barmak Nassirian, associate executive director of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. “The admissions process is designed around data integrity…. We have [verification] techniques that have evolved over time, none of which is absolutely foolproof…. No institution can afford to verify everything people submit.” Robert Bardwell of the American School Counselor Association says, “You have to assume people are honest.”

It’s not just admissions, though. Suzanne Pomey was a working-class Kentuckian who, in 2002, was charged alongside another student with embezzling more than $91,000 from the student group Hasty Pudding Theatricals. More recently, there was Kaavya Viswanathan (’08), who signed a $500,000 book deal while still in high school only to have her first novel pulled from shelves amid allegations of plagiarism. She’s now in her third year at Georgetown Law.

There have always been con artists, cheats, and thieves, of course. What’s alarming is that these episodes are no longer an aberration, but rather an example of a new era of dishonesty that’s especially pervasive among ambitious, privileged kids, according to psychologists and cultural analysts. Adam Wheelers are becoming much more common, says Jean Twenge, coauthor of The Narcissism Epidemic. “And it’s not just college students. This seems to be a trend among people of all ages. People are cheating at everything. It shows up for young people because it’s the only culture they’ve ever known.”

According to a study coauthored by Twenge and published in the Journal of Personality, cases of high narcissism among college-age kids increased by 30 percent from 1982 to 2006; today, two out of every three students measure high on the narcissism scale. “Someone who’s highly narcissistic thinks, The rules don’t apply to me; I’ll do anything it takes to get ahead; and if I have to cheat, so be it,” says Twenge. White-collar criminals, she notes, are almost always clinically narcissistic. So are reality TV stars.

“Adam Wheeler is an extreme case, but I don’t think a surprising one,” says Callahan, The Cheating Culture author. “The idea that somebody would be so focused on having higher status that they’re willing to risk their entire academic career, not to mention criminal action, suggests just what kind of pressure-cooker time we live in.”

Still, it’s tough to say which comes first: narcissism or the Ivy League. Elite schools tend to produce as many big personalities as they attract. “Certainly there’s some truth to the idea that high achievement…often goes hand in hand with a certain arrogance and self-involvement,” writes Douthat. “And that the kind of people who change the world in dramatic ways aren’t always the kind of people you’d want as next-door neighbors.”

At an elite school like Harvard, temptation to reinvent oneself can be especially tricky. Having spent years distinguishing themselves as the brightest, most talented people they know, Harvard freshmen must endure the shock of suddenly living among thousands of others just like them.

Judging by his record, Wheeler seemed to be your typical undergrad: bright, ambitious, driven. Maybe a bit arrogant, but why shouldn’t he be? As a high schooler at Phillips Academy in Andover, he had aced the SATs and gotten into MIT, where he’d earned straight A’s before deciding to transfer to Harvard for a more-supportive literary community. As he explained in a 2007 e-mail to fellow transfers, with pretension so thick it seemed almost self-mocking, “[At MIT] I was, to put it poorly, suckled upon the teat of disdain…. I was inspired thereby to apply to Harvard, where the humanities, in short, are not, simpliciter, a source of opprobrium.”

Wheeler appeared to flourish at Harvard. By the time he was a senior, he’d coauthored four books with a preeminent humanities professor, was frequently invited to lecture on Armenian literature, had earned $45,806 in grants and aid, and was fluent in Old Persian, Classical Armenian, and Old English (French, too). He’d received more than 15 academic prizes, including, as a junior, the prestigious Thomas T. Hoopes Prize for a project titled “The Mapping of an Ideological Demesne: Space, Place, and Text from More to Marvell.” (He’d been the first nonsenior to earn the award.) But those who knew him say he was modest about his achievements. As far as anyone could tell, he was just another ambitious Ivy Leaguer. Except, of course, the Adam Wheeler they knew didn’t really exist.

Harvard students are divided on the subject of his duplicity. A few blame Harvard admissions for inadequately vetting Wheeler’s application, which authorities say included forged transcripts showing him getting A’s as a freshman at MIT — a school that does not issue letter grades to first-year students. “[The Adam Wheeler case] makes it seem as if the people who are deciding who gets in and who doesn’t are absolute morons (hence putting greatly into question the legitimacy of those who actually go to Harvard),” wrote one Harvard Crimson commenter on the newspaper’s website. “This kid broke through the system and now will likely make millions in a book deal.”

Other students, though, praise Wheeler’s ingenuity, throwing out words like “genius” and “poster boy for situational ethics.” Facebook groups like “Free Adam Wheeler!” and “Adam Wheeler is a Genius” celebrate Wheeler as both physically attractive (“I think Adrien Brody could play Adam in the movie, no?” reads one Facebook post) and as “someone who fought the system and almost won.”

Many, like T-shirt entrepreneur Jim McFadden, have mixed feelings. “Someone like [Adam] and his actions cheapen the work that the rest of us legitimate Harvard students put toward our accomplishments,” he says. And yet, “We did, however, think it was pretty badass that he could pull off such a ruse for so long.”

Indeed, there is a sense that when it comes to getting into an elite school — and surviving there — gaming the system is part of the deal. While top-flight schools certainly make exceptions to admit academically subpar students (often athletes, legacies, or children of donors), Wheeler is commended, in a way, for getting in “on his own.” He neither inherited nor bought his way in; he worked for it. “[Adam Wheeler has] learned our language, mastered our ways, and taken the self-promotion and ambition that we’re all groomed for — yes, all — to its natural conclusion,” wrote Alex Klein, coeditor in chief of the Ivy League news and gossip blog IvyGate. “If it walks like an Ivy student, talks like an Ivy student, then it is, without a doubt, an Ivy student.”

Says Klein, “Knowledge of the system is one of the core tenets of an Ivy League education. The Wheeler phenomenon is that, taken to high art form…. When you think of the Ivy League as a place for self-aggrandizement, which it often is, Adam Wheeler becomes the model Ivy League student.”

Or, as one IvyGate blogger wrote: “[Adam] got into the Ivy League the real fucking way — he picked himself up from his bootstraps, and without the help of Mommy, Daddy, and Kaplan SAT review. While he might not have the degree to prove it, Adam Wheeler probably learned more getting into college than most students learn in four years spent here legitimately.” Wrote one Crimson commenter: “Adam did something that most people are scared to do, which is fight for something he wanted. Most people go about it on the same path: good grades, SAT scores, connected families, etc. But Adam saw another path, a path not any easier, certainly not any safer, and most certainly not without consequence. I respect the creativity and genius that Adam showed in doing something not many people can do.”

Twenge, for one, isn’t surprised by such reactions. “This is what happens when you have a narcissist culture and the sort of insane competition in college admissions, which many people think is not fair,” she says. “And they’re probably right. Eighty percent of the applicants can do the work, but only 6 percent get in. When it’s seen that way, there’s a growing aspect of, ‘Okay, let’s game the system.’”

In late September, his Rhodes application file was referred to the Administrative Board of Harvard College, which launched a full and immediate review of his academic history. Wheeler was asked to defend himself at a university disciplinary hearing on the allegations of plagiarism and falsifying documents, according to prosecutors. He declined, saying he’d go home to his parents’ house in Delaware to await the school’s verdict.

Wheeler, as everyone by now knows, turned out not to be a private school prodigy who had aced his SATs and delivered lectures on Zoroastrian cosmology, but rather a public school graduate who had scored a more-modest 1160 and 1220. He’d earned a spot in the top 10 percent of his class but wasn’t valedictorian. He had never attended Phillips Academy or MIT, though he had gone to Bowdoin College before being suspended his sophomore year for “academic dishonesty,” prosecutors say. Among the documents he’s now accused of fabricating: letters of recommendation from four MIT professors and Andover’s director of college counseling, transcripts from Andover and MIT, and “official” results from the College Board.

Even as Harvard debated his fate, Wheeler, back home in Delaware, began readying his next round of transfer applications, which he submitted to schools including Yale, Brown, and Stanford last January. During a routine background phone call to Wheeler’s old high school, Yale admissions officials realized the discrepancies in his application and informed Wheeler’s parents, Richard and Lee Wheeler, who own an interior design firm in Lewes, Delaware. The Wheelers insisted that their son tell Yale of the mess at Harvard. (The Wheelers did not respond to requests for an interview.)

By the middle of May, of course, the Middlesex County DA had indicted Wheeler on 20 mostly felony counts of larceny, identity fraud, falsifying an endorsement of approval, and pretending to hold a degree. He pleaded not guilty, and his trial is set for February. But this spring was not all bad for Adam Wheeler. He was accepted by Stanford, at least for a little while.