Bad Medicine

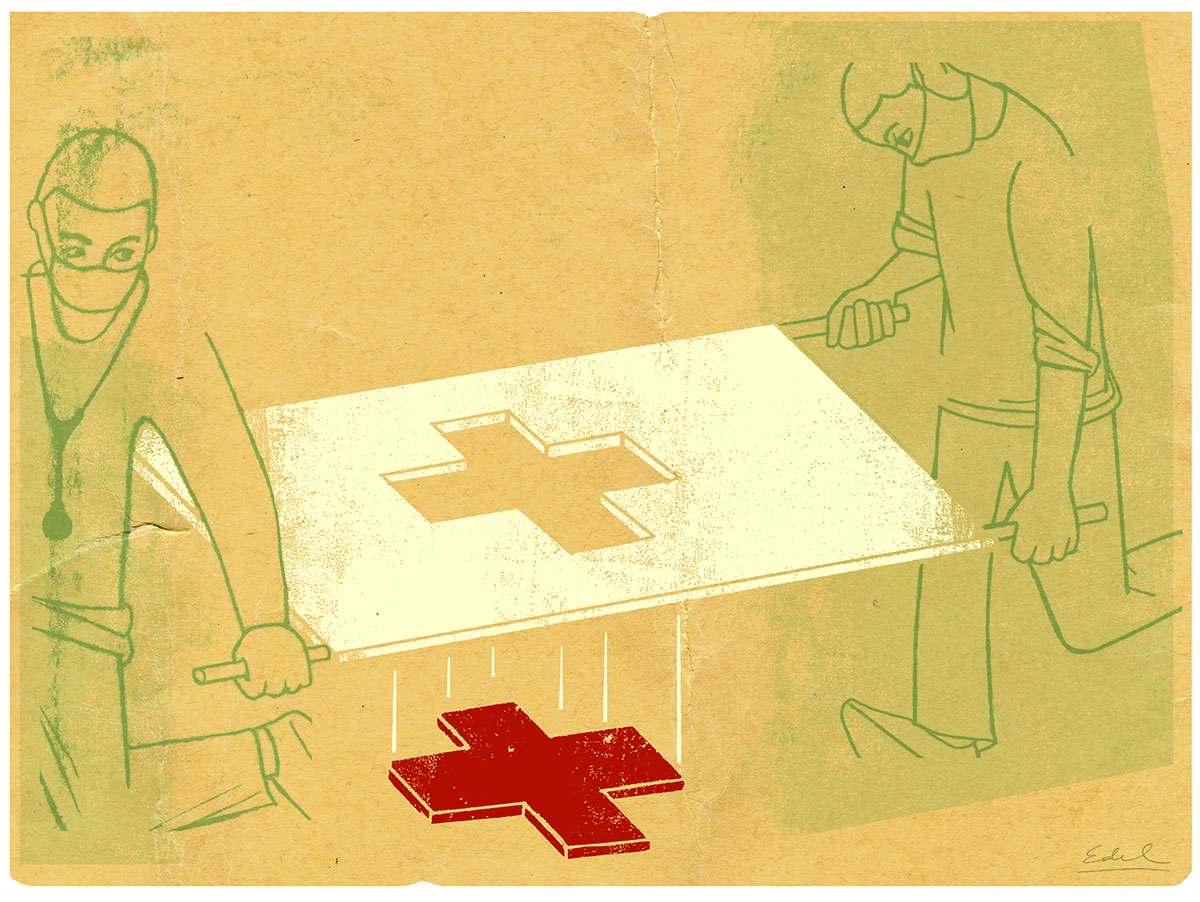

ILLUSTRATION BY EDEL RODRIGUEZ

In the emergency room, a doctor is trying to save a 39-year-old man with multiple gunshot wounds. In the nursery, nurses are weaning a newborn from opiates transmitted during pregnancy. In pediatrics, what initially looks like a simple case of bed-wetting will require the intervention of hospital lawyers and social workers to relocate the traumatized child and mother from a violent public housing project.

It’s just another Tuesday at Boston Medical Center, and the afternoon is playing out here the way it does most days — with a mix of the hopeful and the horrific. The hospital’s food pantry, which serves 7,000 people a month, is crowded with patients clutching doctors’ “prescriptions” for free groceries. A substance abuse team is back from court, having secured a commitment for alcohol treatment for a woman who has been regularly showing up drunk in the ER. The pharmacy is filling a prescription written at a rival Boston hospital that would not honor its own script — because the patient could not pay. Pharmacists fill so many of these that they are unfazed when patients hand over discharge instructions from a wealthier hospital that include directions to BMC.

This place is not to be confused with Boston Med, the “reality” TV show about the city’s private Harvard-affiliated hospitals, which recently ended eight weeks of entertaining melodrama on ABC. There is nothing entertaining or mellow about the drama at BMC, which has provided life-sustaining medical care to the most vulnerable residents of Boston for 146 years. But this much longer-running show is also poised to end its run.

Boston Medical Center is almost broke, perilously close to what its accountants euphemistically refer to as the “zone of insolvency.” It did not get here — $175 million in the red for the fiscal year ending September 30 — because it bought too many MRI machines or banked on cosmetic surgery being a big income generator. It landed in this hole because the folks on Beacon Hill like the sound of universal healthcare a whole lot more than they like the cost of it.

BMC is locked in a battle with the Patrick administration over dramatic cuts in how the state pays for treating the poor. Barring a last-minute settlement, a Suffolk Superior Court hearing on September 29 will consider the state’s motion to dismiss a BMC lawsuit that challenges Massachusetts’ reimbursement rate. (The state currently pays the hospital 64 cents for every dollar it spends on patients with Medicaid.)

BMC says the new reimbursement formula violates state and federal law, and will sound the death knell for the state’s largest safety-net hospital. The commonwealth says it has the power to set any rate it wants; if BMC finds the payments inadequate, it can simply stop taking Medicaid patients. The state’s argument might have some merit in the case of doctors being free to choose their patients, but it’s a ludicrous posture to adopt toward an inner-city hospital that is required — by state law — to serve all comers.

Boston Medical Center was formed in 1996 from the merger of Boston City Hospital, the first publicly owned municipal hospital in the nation, and its private South End neighbor, Boston University Medical Center. To preserve BCH’s long-standing mission to serve the poor, lawmakers wrote that obligation into legislation that created the new quasi-public hospital. Boston Medical Center, the statute stipulates, must “consistently provide excellent and accessible health care services to all in need of care, regardless of status or ability to pay.” The state, in turn, must compensate BMC for treating a disproportionate share of low-income patients by paying “rates that equal the financial requirements of providing care to recipients of medical assistance.”

BMC has kept its part of the bargain. Seventy percent of its patients are poor, elderly, disabled, or members of ethnic and racial minorities. More than 50 percent rely on free care, Medicaid, or state-subsidized insurance plans like Commonwealth Care. Many live in Boston’s most impoverished neighborhoods, and more than 30 percent speak a primary language other than English.

The commonwealth has failed to uphold its end of the deal. The state that has been so successful in expanding insurance coverage — Massachusetts has the lowest number of uninsured residents in the nation — has been caught flat-footed by a struggling economy and skyrocketing healthcare costs. The Patrick administration has chosen to help fund the expenses incurred by new enrollees in Medicaid and Commonwealth Care by cutting payments to the very hospitals that care for those patients. It turns out that expanding insurance coverage is not the same as actually paying for it.

That is not how it was supposed to work. The state had planned to pay for expanded insurance coverage in part by eliminating millions of dollars in supplemental payments to safety-net hospitals, which provide free care to the uninsured. With fewer uninsured, the thinking went, there would be less need for those payments. Medicaid reimbursement rates would rise to help those hospitals care for the newly insured. Instead, the Patrick administration is phasing out those supplemental payments — at the same time it is reneging on its promise to boost Medicaid rates. (BMC is not alone in the resulting financial crisis. Cambridge Health Alliance, the second-largest safety-net provider in Massachusetts, needs a buyer or a deep-pocketed partner to stay afloat.)

Medicaid, one of the largest line items in the state budget, is a politically tempting place to cut. Unlike other areas of the budget — local aid, education, and public safety — healthcare for the poor does not have a vociferous constituency mobilized to express its dismay at the polls. And the state’s plea of poverty doesn’t play when, under the new national healthcare law, Massachusetts is slated to receive a $2.3 billion boost in federal Medicaid funds over the next 10 years.

For the state to argue that it cannot continue to pay for healthcare costs is to duck its own failure at curbing those costs. The governor and lawmakers have yet to act on a report, issued more than 14 months ago by a special commission, that urged an overhaul of how hospitals and doctors are paid. Demanding that BMC simply cut its way to solvency is as glib as promising that every government budget can be balanced by eliminating “waste, fraud, and abuse.” Of course programs should be reviewed for inefficiencies, but there is no getting around reality: It is more expensive to treat the patients who come to BMC.

BMC is not a “treat and street” triage hospital; its integrated system of care means everything from coordinating a cancer patient’s multiple appointments to ensuring that a geriatric patient is eating as well as taking medication. It means providing backpacks stocked with basic necessities for children being moved to emergency foster care. It means understanding the relationship between the city’s infant mortality rate and the spike in clinic visits as a result of babies suffering from “failure to thrive.”

You cannot calculate those costs the way you price out a new CAT scan machine. The hospital has cut where it could, consolidating its two emergency rooms into a single location, for example. But 67 percent of the city’s trauma cases still pass through BMC. And the hospital has been tapping its cash reserves to the tune of $10 million a month, a pace that spells bankruptcy by this time next year.

Governor Patrick has bristled at suggestions that he is indifferent to the poor. Last winter he wrote a testy letter to Edmond English, BMC’s board chairman, to protest just such intimations: “In a time of scarcity, HHS [Health and Human Services] Secretary JudyAnn Bigby and I have to address high costs. Trying to do so does not mean we are insensitive to BMC’s mission. It means we are doing our jobs.”

But Patrick’s job also entails finding a way to keep BMC’s doors open until he helps forge a consensus on how to rein in costs. That’s called leadership.

In the end, the issue is one of basic economics. BMC is being underpaid for caring for the largest percentage of its patients. At the same time, the hospital takes it on the chin from private insurers because it lacks the leverage of a medical behemoth like Partners HealthCare, which can wring higher payments out of insurance companies. Does anyone really think Brigham and Women’s and Mass General would absorb BMC’s patients if it goes under?

Last spring, mediation between BMC and the Patrick administration collapsed after six months. In the past few weeks, Patrick and Bigby have talked with Kate Walsh, the hospital’s new CEO, in an effort to resolve the dispute outside of court.

BMC is not just a safety-net hospital. It is one of the city’s largest employers, with 6,000 full- and part-time employees. The statute that created it mandated that BMC fulfill a role as a “major academic medical center, including support for biomedical, public health, medical education, and basic science research.” It has done that, attracting federal and philanthropic grants to support construction of a cancer center and an outpatient facility, fund clinical trials, and facilitate the training of Boston University medical school students. These are not luxuries. Cancer is the leading cause of death for Boston residents, and BMC is among the few places that introduce students to the genuinely diverse city in which they live and work.

This particular Tuesday is slipping away at Boston Medical Center. The hospital’s motto of “exceptional care without exception” is being played out across its busy campus. The newborn being weaned from addictive drugs could remain in the nursery for weeks. The bed-wetter has been discharged and is being settled into a new apartment, her incontinence gone, along with her fear. The gunshot victim has died.

Each of them was a Medicaid patient. And each of them got more from Boston Medical Center than the Commonwealth of Massachusetts says they are worth.