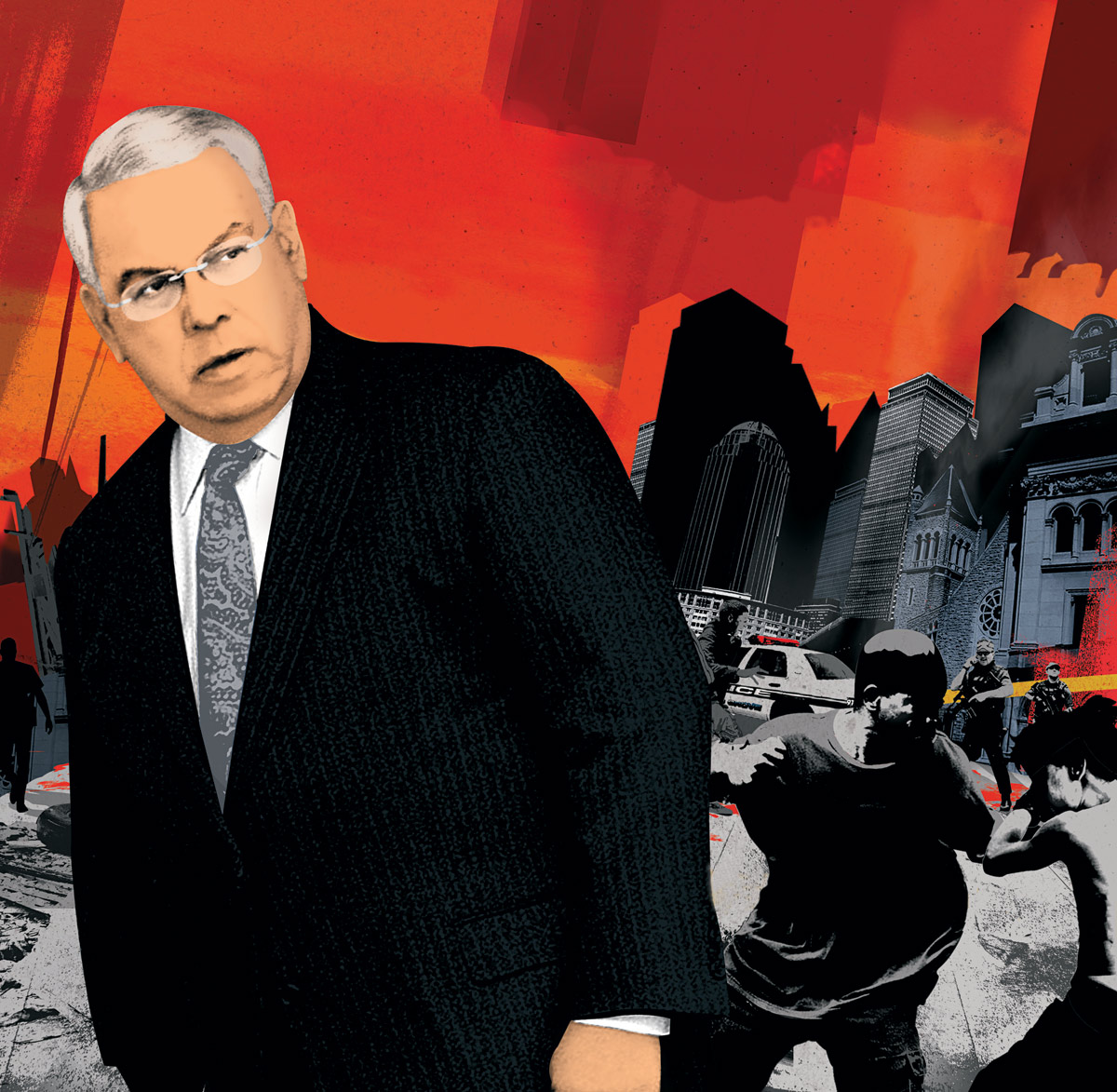

Tom Menino: Meddling While Boston Burns

Illustration by John Ritter

IT WAS A TYPICAL TOM MENINO plan, by which I mean a plan to pile on top of so many others, accumulating like the snow of all the winter’s storms. The mayor highlighted it in Faneuil Hall while delivering his 18th State of the City address this January. All anyone would talk about later was that he’d entered to the theme from Rocky (take that, would-be successors!), and that he’d emphasized his resiliency by standing behind the podium without crutches, despite the surgery he’d just had on his right knee. The theatrics could have been enough to distract anyone from dry policy drivel, yet the policy held its own. Because the plan I’m talking about ended up revealing more about Menino than a soundtrack ever could.

His proposal called for the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives to partner with the Boston Police Department on a new task force. The hope was to take guns out of the hands of bad guys. This seemed like a fine idea. Seventy-two people were killed in Boston in 2010, a nearly 50 percent spike over the previous year. So something had to be done, right? But Boston needs another task force, another new policing initiative, like the mayor needs to test his frail knee on an icy Comm. Ave.

Since 2005 Menino has introduced more than a dozen different police efforts — and these are just the ones on the mayor’s website. That doesn’t include what he’s promoted in his State of the City addresses, ideas such as the Mayors Against Illegal Guns program in 2007, or the partnership with the Boston Housing Authority in 2008, or this year’s alliance with the ATF. Nor does it include all the programs that carry the imprimatur of Police Commissioner Ed Davis—but also the thick smudge of the mayor’s fingerprints. I’m thinking here of stuff like the Partnership Advancing Communities Together, or PACT, designed by Menino’s close ally, BPD Superintendent Paul Joyce. That one hopes to reduce crime by keeping government players informed of the specific bad guys (read: gang members) that the cops would like to take down.

Joyce’s program falls under the rubric of community policing. So do many of the mayor’s other plans. And it’s easy to understand why. Community policing is a golden brand in Boston, a crime-prevention strategy that long ago sent the number of murders in the city plummeting from a historic high (152, in 1990) to a historic low (31, in 1999). It’s the strategy that helped make Boston cops famous and Boston’s mayor — even when he stumbles over big words — seem very smart indeed. That drop in the homicide rate in the ’90s is still described as the Boston Miracle.

The problem today is what Menino asks this golden brand to represent. The sheer number of community-policing initiatives — new ones are introduced each year, sometimes each month — has left community leaders befuddled. Which plan, again, are we following now? It’s not a stretch to say that Menino, in some capacity or another, has launched 20 different community-policing initiatives in the past five years. Many of them muddle if not contradict others. Some are so many evolutions removed from what worked in the ’90s that they shouldn’t even be called community policing. And, as a whole, they seem to be making things worse. The murder rate did increase by 50 percent last year, after all.

Menino is, of course, a domineering man, overinvolved in everything and impatient with many things. But his concern with crime, with murder in particular, goes beyond impatience. Menino’s freaking out a little bit. It isn’t just that murders were up last year. It’s that those murders were ghastly: stripped-naked men shot execution-style, gunned-down two-year-olds, gunned-down pizza delivery guys. Terrible headlines. Too many of them, and a mayor seems ineffective. If that happens to Menino, his tightly bound legacy unravels. And so the mayor keeps searching for the next miracle. But he fails to realize that his search is contributing to the problem.

HOMICIDES ARE DIFFERENT NOW. They’re predicated on the slightest of slights. Historically, however, murders in this city were tied to gangs dealing drugs. And nobody used to get shot unless what they did harmed the bottom line. “If it wasn’t about dollars,” Vito Gray, a reformed Mission Hill drug lord, once told me, “it didn’t make no sense.”

But this isn’t to say that the underworld acted orderly every day. In 1992, at the funeral service in Mattapan for a young man named Robert Odom, hooded members of a rival gang burst through the doors midservice, shot up the church, and stabbed one teen nine times. The attack horrified the city. Out of that day, though, came Boston’s redemption. An elite force of cops, overseen by Commissioner Paul Evans and organized in part by officer Gary French, concerned themselves with the social issues underlying much of gang involvement: looking at the home life of kids, and keeping track of what they did after school. Religious leaders unified under a new name, the Ten Point Coalition, and did the same kind of social work — finding gangbangers legitimate jobs, for instance. Prosecutors, meanwhile, locked up repeat-offender gang leaders. One got 19 years in prison after he taunted cops by showing them a bullet he held in his hand. Collectively, these works organized around a single community-policing vision: that together the group could not only detect crime as it was happening, but also deter it from happening at all.

It worked. The Boston Miracle sent the murder rate plunging to almost absurd levels and removed top-level criminals from the streets. If anything, the Miracle was too effective. After 2000, with few old-school gang leaders around, the mindset of Boston gangs began to change. No one taught the new guys how to act: The same kids who lacked leadership models in their biological families found no supervision within their surrogate ones, either. And so the murders of the new century began to break the street’s old codes. Hits happened with no regard for the bottom line. Instead these gang members, teenagers and young adults, had petty beefs with one another, and settled them in predictably immature and deadly ways — sometimes in broad daylight, around people of means.

Compounding matters, many of Boston’s community-policing stars had moved on: Prosecutors had been promoted or, like former Suffolk County DA Ralph C. Martin II, had gone into private practice; cops like Gary French had received commendations and now headed up new units, or, like Commissioner Evans, had left the department for new jobs (in Evans’s case, a law-enforcement gig in London). In other words, another leadership vacuum had developed — on the law-and-order side.

As a result, chaos once again reigned. Boston had grisly, even strange deaths: a quadruple murder of four Wakefield High graduates, shot execution-style in the basement of a Dorchester home in which none of them lived. The murder total climbed from 42 in 2003 to 64 in 2004 to 75 in 2005 — a 142 percent increase from 1999. All the while the cops, especially those back at headquarters, fought with one another, ever more publicly, as if blame could slow the rising stats. Boston seemed on the precipice of another degeneration.

Then in December 2006 Mayor Menino hired a new police commissioner, Ed Davis. He had come from the Lowell Police Department, and he promised to bring back the wonders of community policing. Soon after taking his oath of office, Davis promoted Gary French to deputy superintendent, and put him in charge of BPD’s community-policing efforts. Davis was asking French to perform another miracle.

He largely did. From 2007 to 2009, the murder rate inched lower. But as French worked on community policing, so too did the mayor. Menino introduced — officially or through the police department — a flurry of new plans. Many of them, according to civic leaders, undermined French and what he wanted to do. Through a spokeswoman, French declined to comment for this story, but one cop friend of his says French felt marginalized, his ideas crowded out by other, sometimes lesser plans.

The murder rate skyrocketed again in 2010. French, the friend says, felt frustrated. “He’d been frustrated for a long time.” In November, Davis demoted him out of the unit. Davis won’t discuss his rationale, but a spokeswoman says it was French’s choice to leave.

If that’s true, here’s one way to interpret it: The man who helped conceive of community policing grew so disgusted by Menino’s ever-newer plans that his only course of action was to abandon his community-policing leadership role.

HERE’S ANOTHER INTERPRETATION: The crime rate in Boston is also a political barometer. Menino may say Ed Davis runs the police department. But his first call, at 6 o’clock every morning, is with Davis, discussing what happened overnight. When Menino’s son, a detective in the BPD, was questioned by a supervisor about his overtime pay, that supervisor was ultimately demoted. Says one longtime cop, “Davis can’t hire or fire anyone on his command staff without Menino.” As though proving the point, in January Davis promoted one of Menino’s former chauffeurs to the command staff.

This is another way to say that the mayor’s ideas for better policing, frequent as they come, hasty as they may be, always make it to the street. That’s how Boston, three years ago, came up with the Safe Homes Initiative, in which detectives entered residences without search warrants, looking for guns teenagers might have. The haul was never great and the ACLU got righteously ugly about the whole thing, so the city quietly shelved the plan. Or there was that PACT initiative, introduced last summer. That one sounded promising: gather state agencies, cops, and black ministers, show them photos of 240 dangerous, high-impact gang members, and then ask community and government leaders to try to steer the thugs straight before they commit further crimes. Good old community policing. “But we didn’t have any follow-up with the city,” one prominent black minister says. The ministers had one meeting with officials last summer, he says, and then they just…heard this fall that some of the players had been arrested.

The PACT program is a redundancy, anyway. It repeats elements of many of the city’s other community-policing efforts. There are strains of PACT, for instance, in the Boston Foundation’s street-workers program, in which former convicts look for high-impact thugs and work with them to turn their lives around. But because Menino dislikes — and, all right, maybe even hates — the Boston Foundation’s president and CEO, Paul Grogan, on account of Grogan consistently criticizing the mayor’s many initiatives, the foundation’s program is ignored by the police department. Meanwhile PACT, the brainchild of Menino’s buddy Superintendent Joyce, gets the mayor’s blessing.

None of this is a question of whether the police department or Menino cares. As Menino tells me, “I want to make sure that every kid is safe.” It is a question of whether what he’s doing is actually helping — especially when Menino is so often tempted by new ideas. Case in point: Earlier this year the department announced a new focus on older drug dealers and ex-cons as the instigators of crime. Ed Davis believes the rise in homicides last year was partly due to the quasi-legalization of weed; you can keep an ounce on you now, as long as you’re not dealing it. This relaxed stance, Davis thinks, has increased the demand for pot sold on the streets. And this influences the murder rate, because ex-cons look to steal the stashes of current dealers and end up in violent situations. However, community activist Jorge Martinez, of the group Project RIGHT, says drugs play no more of a role in the city’s murders than they ever have. “The problems are the beefs [between kids],” Martinez says. “Same as it’s always been.” The police department says it has stats to back up Davis’s contention, but it refuses to share them with the public.

Why push the ex-con angle at all? Because if you can identify a new cause of a long-standing problem, you can introduce new solutions. The new head of the drug unit, for example, is a hard-ass cop named Bobby Merner who has never had a reputation for tolerating all this liberal, limp-wristed, let’s-look-at-the-underlying-social-issues crap. Merner’ll just take people down. Not for nothing was he promoted around the same time Gary French was demoted.

Menino is nervous. If he’s thinking about his legacy at all — and he has to be, given how unkind the fifth term has been to his aging body — then he’s thinking about the two registers that predict whether a city prospers, which is to say, whether affluent people become long-term residents: decent schools and a low crime rate. (It’s telling how Menino addresses problems on these fronts with the same meddling impatience. Boston Public Schools Superintendent Carol Johnson should buy Davis a beer to commiserate.)

But low crime is even more fundamental than good schools. Menino knows that the industries he’s lured to Boston, the urban core he’s revitalized, the clean parks, graffiti-free subway cars, public theater in the summer, tree lightings in the winter, all his successes, everything that will establish him as not only Boston’s longest-serving mayor but maybe, just maybe, its best, depends first on a low crime rate. Without that, he ends his career on a dismal, dreary note, clouding how history views him. With a high crime rate, Menino becomes the Italian Kevin White.

He is cursed with a certainty that his involvement makes any situation better. “Look, everybody can be critical,” Menino says. “But we have to act…. That’s what I’m about.” Every time he starts something new, though, he’s also starting over. When everything is community policing, the perception is that nothing is. The city does not need 20 different initiatives. It needs a more unified plan, practiced by every neighborhood’s concerned residents. Everything else is superfluous and confounding. Ours is a reactionary mayor. Here’s hoping he reacts to this, too.