Love the Kennedys and Nobody Gets Hurt

From legal threats to smear campaigns, America's most famous family will do whatever is necessary to shut down any media portrayal it objects to. Just look at what happened to the controversial miniseries dumped by the Kennedy Channel. Or to the book I wrote a decade ago.

In the wake of Itzkoff’s article in the New York Times, History executives decided that, as The Kennedys scripts were developed, the network had to be ultracareful.

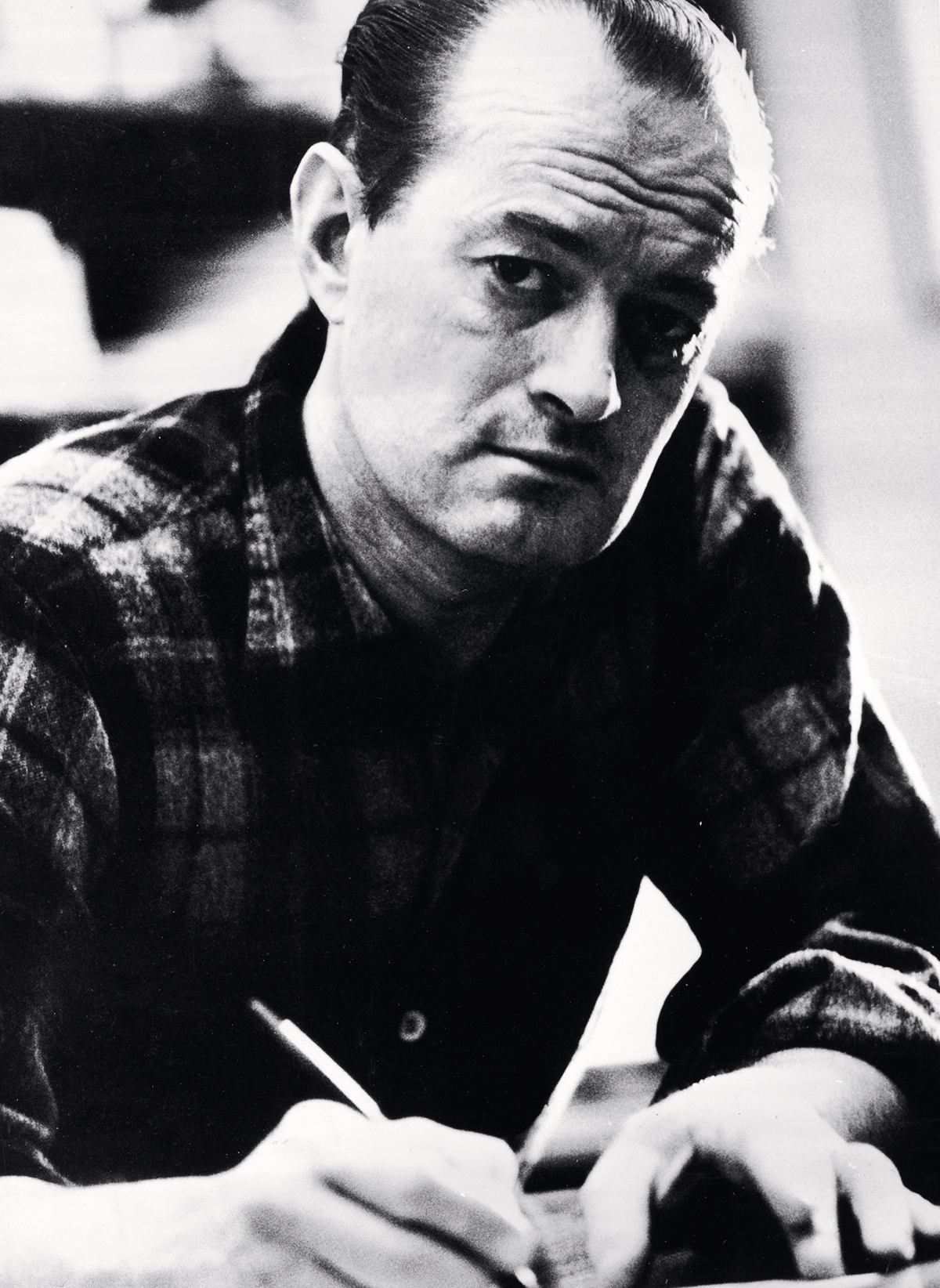

“We were in the middle of writing the shows when we got the word that we needed to make sure there wasn’t a single frame of film that didn’t meet the highest historical standard,” Joel Surnow said. “Everything had to be pretty much double-sourced by very specific scholarly writers. There was the concern that now that we’re actually here [with eight scripts in development], we have to make sure we’re bulletproof historically.”

Both Surnow and Kronish admitted to taking liberties with dialogue and dramatization, particularly with scenes involving the Kennedys’ personal affairs — there was simply no way to write scenes at, say, the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port without inventing dialogue. “There were some characters that became composites, things like that,” Kronish said. “We weren’t doing a documentary.”

Robert Greenwald, meanwhile, worried that, despite his online petition and media blitz, the “political propaganda” was marching forward. “We asked for and could not get a copy of the fixed script,” he told me. It would be unusual for an outsider with no role in the production to see a script, particularly one who’s already denounced the work. But Greenwald said that’s precisely why History should have kept him in the loop. “They were in trouble because they had a front-page story in the Times, and they needed to do damage control,” he said.

Composites and made-up dialogue notwithstanding, Surnow and Kronish told me they were serious about getting the big stuff right, even incorporating direct quotes from Kennedy White House tapes. Plus, they had help: The History Channel had asked historian Steven Gillon to work with the writers to ensure accuracy. The University of Oklahoma professor, who’d deftly handled the controversy with the network’s LBJ documentary, was well qualified for a project blending popular history and the concerns of America’s most famous family: When Gillon was a graduate student at Brown, he’d taught John Jr. , then an undergrad. The two became friends, and John had asked Gillon to write for us at George. Though I haven’t seen him since, I met Gillon during those days, and he was clearly a good friend of John’s. Gillon also had firsthand experience writing history and making television about the Kennedys. In 2009 he published The Kennedy Assassination: 24 Hours After, the basis for a two-hour History Channel special that he hosted.

“We went through draft after draft,” Kronish said of the writing process. “Gillon recognized that we were not doing a documentary, but a historically based drama. He recognized a certain latitude. But when it came to facts about the Kennedys’ political and public lives, we had a couple of arguments because he was very insistent that our sources be academically recognized.” In the end, Kronish said, “they were.”

Scholar Robert Dallek was also enlisted by History. Dallek knew the Kennedy family well: He could not have written his well-reviewed 2003 book, An Unfinished Life, had the Kennedys not granted him unprecedented access to JFK’s medical records. (As Times reviewer Ted Widmer put it, Dallek “received permission from the family’s praetorian guard.”) What had taken so long? Kennedy biographer Richard Reeves once wrote in the Times that the public didn’t know about the president’s illnesses because the custodians of his memory didn’t want them to; after the assassination, “The family and the men who had served him continued the lying and began the destruction, censoring and hiding of Kennedy’s medical records.”

But with access no one else had ever enjoyed, Dallek documented that JFK’s health problems were far more debilitating than previously understood. Due to a litany of ailments, Kennedy had three times been given his last rites, and there was ample cause to wonder whether, had there been no Dallas, he would have died young of natural causes.

An Unfinished Life would also be a major influence on Surnow and Kronish’s portrayal of JFK. Their president is constantly popping pills, suffering injections, and grimacing from chronic pain. For people who don’t know of Dallek’s book, the portrayal could well be revelatory — a fact that applies to many of the incidents presented throughout The Kennedys, which can appear tawdry not because it makes facts up, but because it aggregates so many of the secrets that historians have unearthed about the family.

Neither Dallek nor Gillon would be interviewed for this article. Dallek didn’t respond to several e-mails, and Gillon wrote back only to say, “The story that you are writing is timely and important. Unfortunately, I will not be able to discuss with you anything about my role in the miniseries.” But three sources with firsthand knowledge of the process say that both historians did sign off on the final scripts. Surnow says he even has e-mails from Gillon vouching for the accuracy of each episode. “We went through draft after draft until we got every script approved,” he told me. “Steve Gillon signed off on all the scripts.” Said Kronish, “We would not have been able to film these episodes had the scripts not been signed off on.”

The Kennedys was shot over 72 days in the summer, and then in the fall was edited and went into postproduction. Executives from History closely tracked its progress, watching dailies and visiting the sets — this high-profile miniseries was, after all, a first for them, and they were taking no chances. The show was scheduled to premiere in the spring.

At the same time, though, below-the-surface efforts to torpedo the miniseries were becoming more urgent — and more effective.

For a while, my editor at Little, Brown, Sarah Crichton, fended off the assaults against both American Son and me. In the weeks after she’d verbally agreed to buy my book — in publishing, you get a handshake and then the contract is drawn up — she supported me both publicly and privately. But as the pressure mounted, she eventually stopped taking and returning my phone calls. I was being held at arm’s length.

Adding to my troubles, I had a vulnerability: Like most of the employees at George, I had signed a confidentiality form — drafted by John’s college friend Gary Ginsberg — in which I had agreed not to write about John Kennedy. Did that agreement survive John’s death? No one had even thought about it until now. Out of both principle and self-interest, I argued that it did not.

What happened next remains a matter of significant dispute more than 10 years later. In Crichton’s recollection, she and Little, Brown didn’t learn about the confidentiality agreement until after they made their offer to me. Crichton also says that the reason the deal was ultimately scrapped was that the publishing house’s lawyers felt it presented too much risk. I am certain, however, that my agent and I told Crichton about the confidentiality agreement before she made the offer, and that her lawyers said it was no problem.

Still, weeks were going by with no written contract from the publishing house — and the drumbeat of bad press kept getting louder.

On May 4, 2000, my agent, Joni Evans, got a call from Crichton: Little, Brown was backing out of the deal. They weren’t going to publish American Son. Evans was shocked: In publishing, your word is your bond. But Crichton said the book had become too hot to handle. “They’re killing this book,” she said to Evans. “They’re just killing it.”

Evans called me with the news. I felt sick to my stomach. But at least we would have a little time to weigh our options. Crichton had said that Little, Brown wouldn’t go public with the news until Evans and I had discussed how to spin it in a way that would help us to find a new publisher for a book so embarrassingly and publicly disowned.

Perhaps 15 minutes after that brief phone call ended, my phone rang again. It was Keith Kelly, the longtime media reporter for the New York Post. “How do you feel about Little, Brown dropping your book?” he asked. Half an hour later, I walked outside my apartment to get some air and was ambushed by a camera crew from a tabloid television show. Apparently, Little, Brown hadn’t wasted any time. (Crichton said she did not leak the story.)

The next morning’s Post reported that Little, Brown was cutting me loose. Crichton told the Post she hadn’t been pressured by Kennedy family associates. She “didn’t realize” I had signed a confidentiality agreement, she said. “Knowing that now, I really felt we had no choice but to pull out.” Whether she meant it or not, to me the implication was clear: Not only was I a Kennedy traitor, I was also a liar.

I was stunned — but there wasn’t much I could do to push back. My book homeless, my reputation shattered, I needed another publisher badly, and calling into question the integrity of my former one wouldn’t help my cause.

Crichton never called me, and I hadn’t spoken to her for a decade until I phoned her for this article. After the deal went public, Crichton told me recently, she received a phone call from Esther Newberg about the confidentiality agreement I’d signed. Other phone calls from well-placed New Yorkers followed. “It was clear that these were people who had a close relationship with the Kennedys,” she said. “Nobody said to me, ‘This [Kennedy] told me to call’…it’s just that there are people in New York who have relationships and friendships with the Kennedys and everybody knows that, and they were the ones who were calling.”

The callers’ greatest lever was the confidentiality agreement. “Nobody said directly, ‘If you publish this a lawsuit will be brought,’” Crichton recalled. “But…it felt to me that the threat was real.”

In any case, Crichton said, “You can kill a book without bringing a lawsuit,” and over a period of weeks she had come to the conclusion that American Son had taken too many hits to be publishable. “It became clear that you had a lot of people who were going to rough you up,” she said, “and they were going to have a signed paper to use against you. It just looked too messy.”

In the weeks following Crichton’s decision to abandon the book, my agent reached out to publishers who had previously expressed interest in American Son. The unanimous response: No thanks. My book had been discredited before it had even been written.

So over the course of an anxious, unpaid year, I did the only thing I could. Even without a publisher or an advance, I wrote American Son.

I completed a manuscript in mid-2001. In the interim, George had folded, which eased concerns about a confidentiality-agreement lawsuit. In time, Henry Holt and Company publisher John Sterling offered $300,000 for the book, less than half of what I’d been offered by Little, Brown. That hurt — by this point, I really was unemployed and broke, having gone two years without a salary. But at least my book would finally see the light of day.

Published in May 2002, American Son wasn’t exactly a critical success. The reviews seemed colored by the debate over my character. When I went on Today, Katie Couric’s interview was so hostile one media critic wrote that she talked to me as if I were “a Hamas lieutenant.” Caroline Kennedy had been a guest on the show the day before. So maybe I shouldn’t have been startled when Couric prefaced a question to me by saying, “We spoke with your former coworker actually yesterday, Gary Ginsberg….” How had she gotten that number?

Still, American Son sold well. It spent seven weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, was excerpted in Vanity Fair, and was the subject of a People cover story.

I hadn’t read that People article since its publication until I did so for this story, and was surprised to find the only supportive quote coming from a Kennedy intimate: “John now belongs to history, and I hope that the many people who were close to him will put their recollections on paper.”

The source of that endorsement? Historian Steven Gillon.

With spring fast approaching, the Kennedy family launched an all-out attempt to derail The Kennedys. While no one has told the full story, I’ve pieced together much of what happened based on several Hollywood Reporter and New York Post articles, plus my own interviews with sources.

According to one source, Gary Ginsberg called several newspaper reporters, talking to them off the record. He claimed to have seen the miniseries and called it a “piece of trash.” Then there’s the story that the literary agent Esther Newberg called Caroline Kennedy’s publisher, Hyperion, in December. Caroline is set to publish what promises to be her biggest book yet: transcripts of interviews her mother granted to Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in 1964. The transcripts come from tapes that would be the basis for a planned one-hour television special on the ABC network, which, like Hyperion, is owned by Disney/ABC — which also has a piece of the History Channel. But Newberg reportedly warned that if History ran its miniseries, Hyperion — and ABC — shouldn’t expect Caroline to do much to publicize her book. (Both Ginsberg and Newberg did not respond to requests for interviews.)

Meanwhile, a source said, executives affiliated with History began getting angry phone calls and e-mails from several members of the Kennedy family, including Bobby’s kids Rory Kennedy and Kerry Kennedy, and Caroline’s husband, Ed Schlossberg. Then came a report that former NBC anchor Maria Shriver expressed her displeasure to NBC Universal’s Jeff Zucker and Jeff Gaspin, who also serves on the board of the Arts & Entertainment Television Networks, the History Channel’s parent company.

According to the Hollywood Reporter, a focal point of the pressure was Anne Sweeney, who is president of Disney/ABC — and who is on the board of the Special Olympics, which was founded by Eunice Kennedy Shriver. Sweeney also goes to the same Los Angeles church as Maria Shriver. Sweeney was the recipient of phone calls from both Caroline Kennedy and Maria Shriver. The gist was that 2011 would mark the 50th anniversary of JFK’s inauguration. Caroline wanted nothing to mar that milestone — and The Kennedys was very much a looming black cloud. If The Kennedys were to air, Newberg reportedly explained, Caroline would not be inclined to help ABC with coverage of either her mother’s taped interviews or remembrances of her father.

On January 7, Surnow got a phone call from History Channel president Nancy Dubuc. Once a big believer in The Kennedys, Dubuc was now bearing bad news: The network would not be airing the series. Surnow told me that Dubuc “didn’t give a reason.” (She declined to be interviewed for this article.)

History released a terse statement saying The Kennedys was “not a fit” for its brand. Then, about two weeks later, the Times’s Dave Itzkoff would publish his report of “an unsuccessful yearlong effort to bring the miniseries in line with the historical record.” Surnow’s frustration was evident when I talked to him. “The story of why they killed it is not true,” he insisted. “That is a lie. It had nothing to do with historical accuracy.” In the same conversation, he said, “I am sure the Kennedy family went as high up the ladder as they could to influence people to do their bidding for them. I think it happened.”

One of the strangest elements about the aftermath of History’s move was that, having said it wouldn’t air the miniseries, it now had to convince another network to do just that. It owned the domestic rights to air The Kennedys, so if it were to recoup anything from its investment, it would have to sell those rights. But selling the rights to a miniseries that you’ve just said isn’t good enough for your network is no easy thing to do.

HBO and Showtime didn’t want it. HBO is working on another Kennedy drama, and besides, it has a long-standing relationship with documentarian Rory Kennedy, having aired several of her films. In any case, nobody wanted to look like they were picking up History’s sloppy seconds.

Almost all the cable channels, it seemed, had relationships either with the networks or with the Kennedys. One channel that didn’t — The Kennedys’ ultimate savior — was a relatively small cable outfit called ReelzChannel. Prior to this whole saga, you’d probably never heard of Reelz. Based in New Mexico, it airs mostly movies and shows about movies, and it’s privately owned by members of the Hubbard family. “We’re an independent network, and we don’t have to worry about corporate boards,” ReelzChannel CEO Stan Hubbard told me. Hubbard says that politics had nothing to do with his decision, but if the Kennedys were worried about politics, they’d just sent the miniseries from the frying pan into the fire: The Hubbard family, including Stan, have a track record of making substantial contributions to conservative Republican political candidates.

On February 1, ReelzChannel announced that it would air The Kennedys. The series premiere delivered 1.9 million viewers, a record for Reelz. And that is another irony: As was the case with American Son, the controversy over Joel Surnow’s miniseries has quite likely made it better known and more sought out than it otherwise would have been.

Nobody can blame the Kennedy family for caring deeply about how its members are portrayed. But shouldn’t they voice their objections in public? Caroline Kennedy could quite easily make the case that she doesn’t think the miniseries depicts her family fairly. It’s not as if she doesn’t have ample access to the media. She could have said that she didn’t think her brother would have wanted me to write a book about him. Why not let the marketplace of ideas go about its business? All these back-room campaigns, these anonymous machinations, suggest a lack of faith in the American public — maybe even in the Kennedy legacy itself. It is elitist in the worst sense of the word, and it winds up inflicting far more damage to the legacy than any book or movie possibly could.