Can These Styles Save Talbots?

In a recent marketing survey, Talbots asked a group of women, all of them above the age of 65, to describe the chain’s typical customer. The overwhelming response: “Someone older than me.”

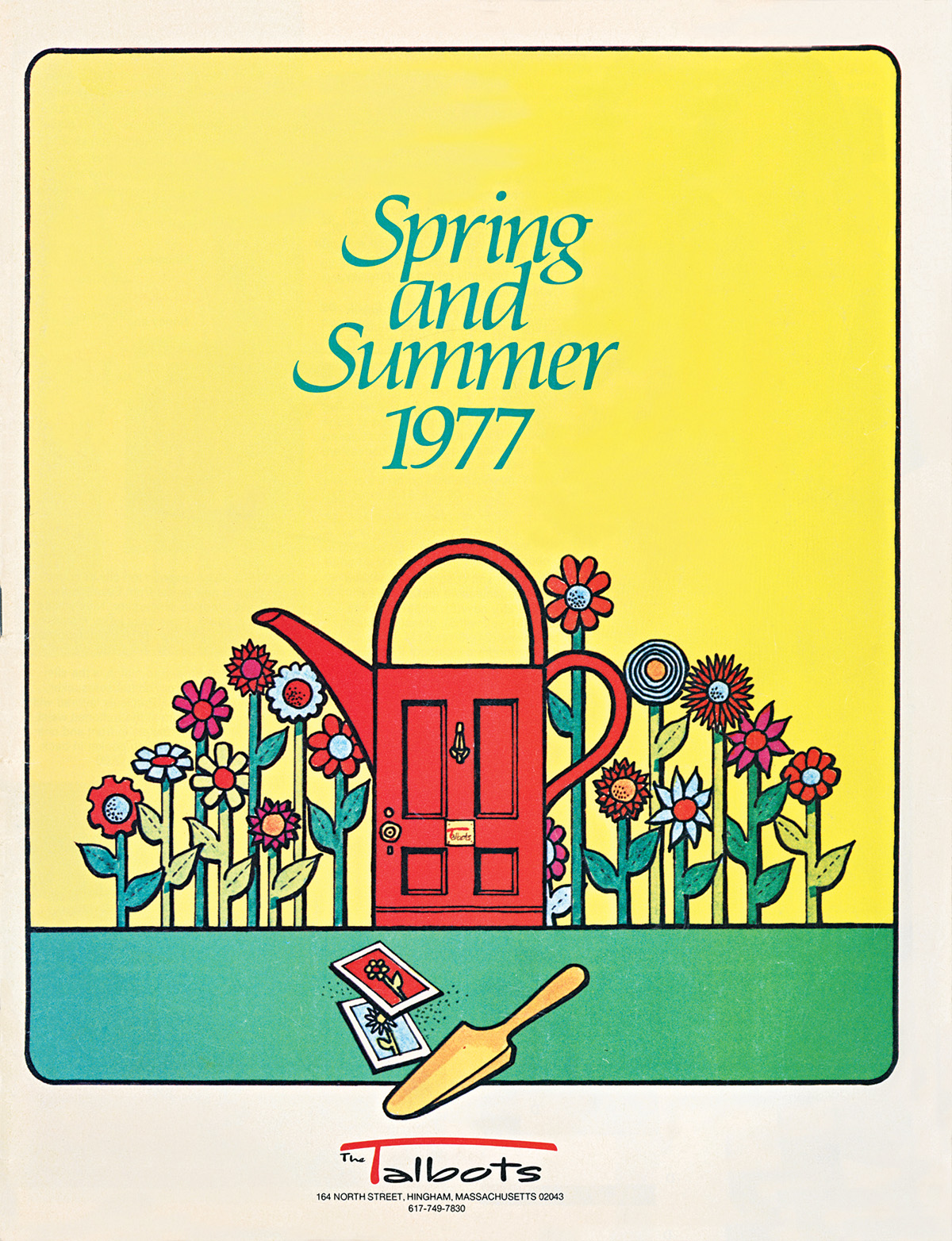

Talbots was founded in Hingham in 1947, catering to a particularly New England sensibility that cofounder Nancy Talbot described as “simple but not contrived, gimmicky, or extreme, smart but not faddy, fashionable but not funky — chic and understated, the hallmarks of good taste.” And for a long time the company delivered exactly that — its clothes were even name-checked in the Official Preppy Handbook in 1980. Somewhere along the way, however, the admirable pursuit of good taste led to Talbots developing a stubborn reputation for frumpiness. These days, no matter how old you are, it seems that Talbots is making clothes for people older than you.

That perception was Trudy Sullivan’s main problem when she started as Talbots president and CEO four years ago, and it’s her main problem right now on this morning in March, as she’s presenting the company’s most recent financial numbers during a conference call with retail analysts.

Sullivan was hand-selected — plucked away from Liz Claiborne in 2007 — to turn around the fortunes of the 64-year-old women’s apparel brand. But the company has continued its bumpy ride throughout her tenure. After Sullivan took over, Talbots shed hundreds of jobs from its Hingham headquarters and shuttered its men’s and kids’ divisions. Despite these cost-saving moves, though, the company’s stock plummeted by 80 percent, to a low of $1.19 a share in December 2008 — which led to Internet chatter warning consumers against purchasing Talbots gift cards since the chain was in danger of going out of business.

The following year, Sullivan made the bold decision to unload the Quincy-based clothing retailer J. Jill, which Talbots, in a disastrous deal, had acquired in 2006 for $517 million. Sullivan sold the company for $75 million, a staggering loss, but the move helped Talbots climb out of debt. Still, the company’s earnings dropped so low in 2009 that Talbots landed on The Wall Street Journal’s retail deathwatch list.

After a few promising steps toward recovery in 2010, the company’s earnings dipped again, with a fourth-quarter loss of $2.8 million. And 2010 revenue dropped to $1.21 billion, down from $1.24 billion the year prior.

Read About Nancy Talbot in Her Daughters’ Words

Now, as Sullivan is presenting her company’s 2010 earnings report, she sketches out her latest strategy to overhaul the struggling brand. First, she says, Talbots is going to shed dead weight by closing 100 stores by year’s end. Next, the successful stores in the chain will get a “facelift” that will involve updating the window displays and painting over the iconic red doors. Other fresheners include a more modern product line and increased financial flexibility. It’s all part of the carefully calibrated approach that’s needed, she says, for Talbots to attract new customers without alienating its base.

The nips and tucks that Sullivan is prescribing seem to do little to appease the retail analysts on the call, though, especially when the CEO reports that early returns on the updated clothing line have been less than promising. Shoppers were confused by the more fashion-forward approach in the January catalog, which Sullivan acknowledges “didn’t resonate with our customers.”

Finally, one analyst, an exasperated edge in her voice, demands, “Who is the customer and where does Talbots sit? Do you think you have the product figured out? That’s what I’m struggling with. Maybe you don’t have it figured out.”

Less than three miles down the road from the Talbots headquarters is the crisp white 17th-century Colonial in Hingham where Nancy and Rudolf Talbot first started the company. Today it remains just as they left it: The legendary bright red door still has its shiny brass knocker cocked slightly to the side.

Inside, several women dressed in Easter-egg-colored raincoats — their ash blond hair trimmed into neat chin-length bobs — weave their way through the racks of ruffled tees, linen pants, cardigans, and chinos.

When the Talbots opened the store in 1947, their timing was perfect. The postwar boom had ushered in an era of prosperity, and the couple was selling quality, well-priced American sportswear — twinsets and blazers, ballet flats and pearls — to a new generation of young families. After procuring the addresses of 3,000 New Yorker subscribers, the Talbots expanded their reach by launching a catalog in 1948. Working with the Beans and other New England retailers dabbling in the mail-order business, they increased production and inventory until their circulation reached more than 10 million.

Nancy Talbot “was very opinionated about how people looked. She could spot people with a certain sense of style,” says her daughter, Polly Donald, now a retired school headmaster in Boulder, Colorado. Jane Winter, Nancy’s younger daughter, says her mother “loved chic, she loved sharp. She had a good eye for fit. She’d say, ‘Change the waist or hip. Make it narrower or bigger.’ She could suggest alterations, and the manufacturer would make them.”

By 1973, the Talbots had successfully opened five stores in New England. They eventually accepted a $6 million offer from General Mills to buy the company, with the understanding that they would continue to oversee the brand. Rudolf retired in 1974, but Nancy was named vice president and worked with General Mills for the next nine years. “She worked so hard, and was flying back and forth to New York two times a week,” Winter remembers. “I think they were trying to find someone to replace her, but to her no one would ever do it right. You cannot give someone else your taste, you can’t train them.”

Nancy retired in 1983, and the company continued to grow for the next two decades, especially after General Mills sold the brand to a Japanese conglomerate in 1988. The new owners took the Yankee, town-center concept and pushed it into malls across the country. At its peak, the business that started out in a clapboard Colonial had grown to nearly 600 stores with annual sales of more than $1.5 billion.

But with a formula that consisted mainly of power suits and pearls — Barbara Bush was practically an ambassador for the brand — the company became complacent. “They were operating on autopilot,” says Jennifer Davis, a retail analyst with Lazard Capital Management. Alice Demirjian, the director of the fashion marketing program at Parsons the New School for Design, says Talbots “epitomized East Coast style and tailoring, but it developed a brand image that was stuck in the boxy-looking classic pieces. It didn’t feel like it matched how women were evolving.”

“I think what happened is it didn’t reinvest and reinspire and renew itself,” says Susan Plagemann, the publisher of Vogue. “It cost them their relevance.”

As a consequence, the brand began to age along with its client base, losing its signature spark and entering frumpy territory. This frustrated no one more than Nancy Talbot herself. After leaving the company, her daughter Polly Donald says, “She hardly ever shopped at Talbots. She became a Saks fanatic. She’d say that Talbots was boring. They were trying to be what they thought Talbots was — something simple, not trendy — but they lost sight.”

Given the company’s long list of challenges, Trudy Sullivan describes the situation she encountered on her first day on the job back in 2007 as “scary.” But right now, sitting at the head of a boardroom table that could double as a runway at Talbots’s 53-acre Hingham campus, Sullivan is talking wizards. “We have about 15 of them here,” she says. “And then we have a chief wizard.”

The wizards are the team who handle Talbots’s Facebook page, which has more than 115,000 fans and serves as a de facto customer service center. The page’s devotees do all the usual Facebook things — post photos of themselves in their Talbots outfits, share concerns about fit or fabrics — but they are also able to use the page in quite an innovative way: They can reach out to the wizards for help finding the perfect flyaway cardigan, poet shirt, or snakeskin pumps. “The wizard is an example of modernizing the brand, and it’s true to our heritage of customer service,” says Sullivan. “It’s an intense relationship. You’ll read comments on Facebook from people who want us to bring back high-waisted pants or docent shoes. But invariably someone else will say, ‘I love the new Talbots look.’”

At 61, Sullivan’s face is framed by a halo of silver hair and tremendous round tortoiseshell glasses. She’s dressed head to toe in Talbots, save for the turquoise Hermès scarf draped around her neck. “Since I walked in here, I’ve only worn Talbots,” she says. “And it was tough in the beginning, let me tell you.” But Sullivan isn’t afraid to take on a tough situation.

She grew up in Wellesley as the second of six children, and has memories of Talbots that stretch back to her youth. “I wore the clothes, my mother wore the clothes, my sisters wore the clothes,” she says. When she summered on the Cape, she’d visit the Osterville store: “You could buy everything there, from ballet flats to outerwear.” Sullivan’s love of shopping led her father to encourage her to make it a career, so she enrolled in a postgraduate course in retail at Simmons College. From there, she entered the Jordan Marsh training program “and never looked back.”

Sullivan thrived in retail, quickly becoming a cult figure on the Jordan Marsh selling floor, known for her ability to get inside her customers’ heads. At one point, she was actually courted by Nancy Talbot, who saw a glimmer of herself in the young buyer and tried to recruit her. “She was very smart and she knew what her customers wanted,” remembers Jerry Finegold, a salesman who worked with Sullivan at Jordan Marsh in the ’70s. “You knew immediately that she was going bigtime.”

But despite her knack for dressing others, Sullivan often came up short when dressing her own plus-size frame — it was impossible for her to find clothing that was tasteful and well designed. If you were a larger woman, “you fell off the fashion radar,” she recalls. So she approached her father, Gerard Fulham, an entrepreneur who ran Pneumo Corporation in Boston, about opening a clothing store for affluent women who wore larger sizes. When he pointed out that, at 28, she lacked management experience, she moved to Filene’s and spent seven years on the management track.

In 1985 her father finally agreed to help fund her venture. Sullivan and her husband, Michael, used their life savings to open the first T. Deane store in Wellesley. After doing more than $1 million in sales that first year, Sullivan attracted interest from venture capitalists, who fronted the cash to expand and pushed her to be aggressive. Before turning 40, she’d opened 21 stores and had reached annual earnings of $15 million. The stores were profitable, and retail analysts predicted that T. Deane would become a major chain. But in 1990 the bottom fell out. In her push to expand, Sullivan overextended herself and ultimately had to declare bankruptcy, taking a financial loss of $11 million.

Unbowed, Sullivan fought her way back into retail. The owner of the Decelle’s clothing stores in Massachusetts hired her shortly after the bankruptcy filing, saying he admired her grit for going out on her own. She was quickly promoted to president. From there, she was tapped to head J.Crew, where she grew the chain from 20 to 100 stores. In 2001 she became president of Liz Claiborne, overseeing $5 billion in annual revenue from its collection of powerhouse brands like Juicy Couture, Kate Spade, and Lucky Brand Jeans. But after six years with Claiborne, Sullivan’s role shifted and she was put in charge of the company’s lesser-performing labels, such as Liz Claiborne, Dana Buchman, and Ellen Tracy. Then, when Claiborne was looking for a new CEO, she was passed over for a 43-year-old male executive from outside the company who had zero fashion experience.

When the Talbots opportunity arose, Sullivan jumped at the challenge. “I loved the brand, and I loved the shot of leading a change of this magnitude,” she says, swiveling in her chair at the head of the boardroom table. “In our industry, if you get to work on a turnaround on a brand like this, it’s really a game-changer for your career. For me I look at it as a career capper.”

When Sullivan arrived at Talbots in 2007, the brand’s profits had dropped to $31.6 million, down from $93.2 million the previous year. The “timeless” look that the company had come to stand for had largely been undermined by the rise of fast fashion, with designs from the runway landing on the retail floor in a matter of weeks.

In this environment, Talbots was largely ignored, if not openly scorned, by the fashion community. Sullivan’s top priority, then, was to stop the trash talking. “Dowdy is dead,” she announced to the press. Then she set out to recruit a team to help rebuild the brand.

One of her first moves was to bring in Michael Smaldone, who came from creative roles at Banana Republic and Ann Taylor. Smaldone was hired as chief creative officer, and says he was flabbergasted when he began to examine the job ahead of him. “It was astonishing to me that a brand could get to be that size and lose its relevancy that much,” he says. “It felt like it was so out of touch with what the modern woman’s lifestyle was like.”

Sullivan and Smaldone got to work creating a war room filled with classic pieces, old catalogs, and inspirational photos. They developed their brand book — words and mantras to begin redefining the company: “Classic not conservative. Charming not darling.” The team also came up with a new motto for Talbots — “Tradition Transformed” — and a series of catch phrases to describe the company’s “40ish” consumer. (During interviews, in fact, Sullivan and Smaldone each describe “40ish” as “not an age, but a stage” with a regularity that seems at times to be a kind of tick.)

The new leadership duo also fired the entire creative department in New York, and began overhauling the product line. Smaldone identified the classic Talbots pieces — ballet flats, twinsets, crisp white shirts — and updated them for a contemporary woman.

They also got aggressive. After years of Talbots nursing cocktails on the sideline, they reintroduced the brand as a consummate hostess. They launched focus groups, began offering in-store parties for their best customers, opened a string of “upscale outlets,” and unveiled a new denim line. Immediately after the presidential inauguration, they began courting Michelle Obama’s former stylist, Ikram Goldman. The first lady wound up wearing a blue and green floral shift from Talbots’s spring 2009 collection on the cover of Essence. “I was crying when I found out,” says company publicist Meredith Paley. The dress sold out in stores; a woman in Dallas who dislocated her shoulder while trying it on handed a clerk her credit card as she was carried out on a stretcher. She refused to take it off. “Michelle’s at the epicenter of our brand,” Sullivan says.

The company also began flirting with the fashion press, offering previews of their upcoming lines and taking out ads in magazines for the first time in a decade. They hired the gorgeous, and more important, ageless Linda Evangelista and Julianne Moore as spokesmodels. And they opened a sleek new concept store this fall in Paramus, New Jersey, that’s designed to be a woman’s “dream closet.”

But the process of transforming tradition has not been without problems. A decision to sell rabbit-fur collars last fall led to protests from the Humane Society, and the clothing was pulled from stores. And the Facebook page often erupts at the wizards over certain styling choices, like the new line of pumps that were dubbed hooker heels: “These look like something a streetwalker would wear,” one woman wrote. “What happened to classic and traditional?”

Other customers say they feel abandoned by the new product line, which can often hew closer to seasonal trends than timelessness: “Where are all of your classic looks for the over-50 crowd?” asked one woman. “Have been a faithful shopper for the last 20 years but am quickly moving away from the store as I am not trying to look like I’m 30-something.”

Retail analyst Jennifer Black doesn’t hide her frustration when asked about Talbots’s uneven effort to reach its target audience. The execution of the overhaul plan sometimes comes up short: Talbots often sells out of popular products quickly, and customers get confused when catalogs fail to sync up with in-store merchandise. And having beautiful new spokesmodels means little when the stores themselves look like they’re straight out of 1987. “I’ve wanted to pull my hair out,” Black says. “It’s been my toughest stock.”

Sullivan and Smaldone, though, remain confident that their product line will eventually appeal to both new customers and many of the die-hards who’ve been loyal to the brand for decades. “We know that we’re going to lose the woman who just wants the powder-colored puffer coats and the Christmas pins,” he says. “But that’s part of the plan.”

In the end, the real challenge is getting those new customers through the door. And in fact, Sullivan says, it’s the door itself — the red one that became the company trademark — that’s keeping Talbots from moving forward. “The red door signals old lady,” Smaldone says in agreement. He adds that, save for the original Hingham location, the company has decided to paint over all the other red doors. What color? “Depending on the façade,” he says, “they’ll just blend in.”

When it’s pointed out to Sullivan and Smaldone that blending in was never part of Nancy Talbot’s vision, Sullivan says, “Red is always going to be part of something that we do here. But the red door very much signals the old Talbots, and our own research indicates that. It’s a bit of a deterrent to get the new customer across the threshold, whereas the loyal customer is going to cross over.”

Whether Talbots will come back and thrive is still unclear. The slight uptick in stock prices early this year had fallen flat by May, with analysts reporting that the product line “lacked direction” and wasn’t resonating with either the company’s core older customers or the new ones it hopes to attract.

Nancy Talbot died in 2009, and you have to wonder what she’d think of the brand today. Would she come back through the painted-over doors after a shopping trip to Saks? “I think what Trudy is doing now would appeal to Mom,” says Polly Donald. “The status quo never really interested her. In today’s world it’s such a competitive market. She knew that if you want to stay current, you’ve got to rethink who you are.”