Fast Times at Marina Bay?

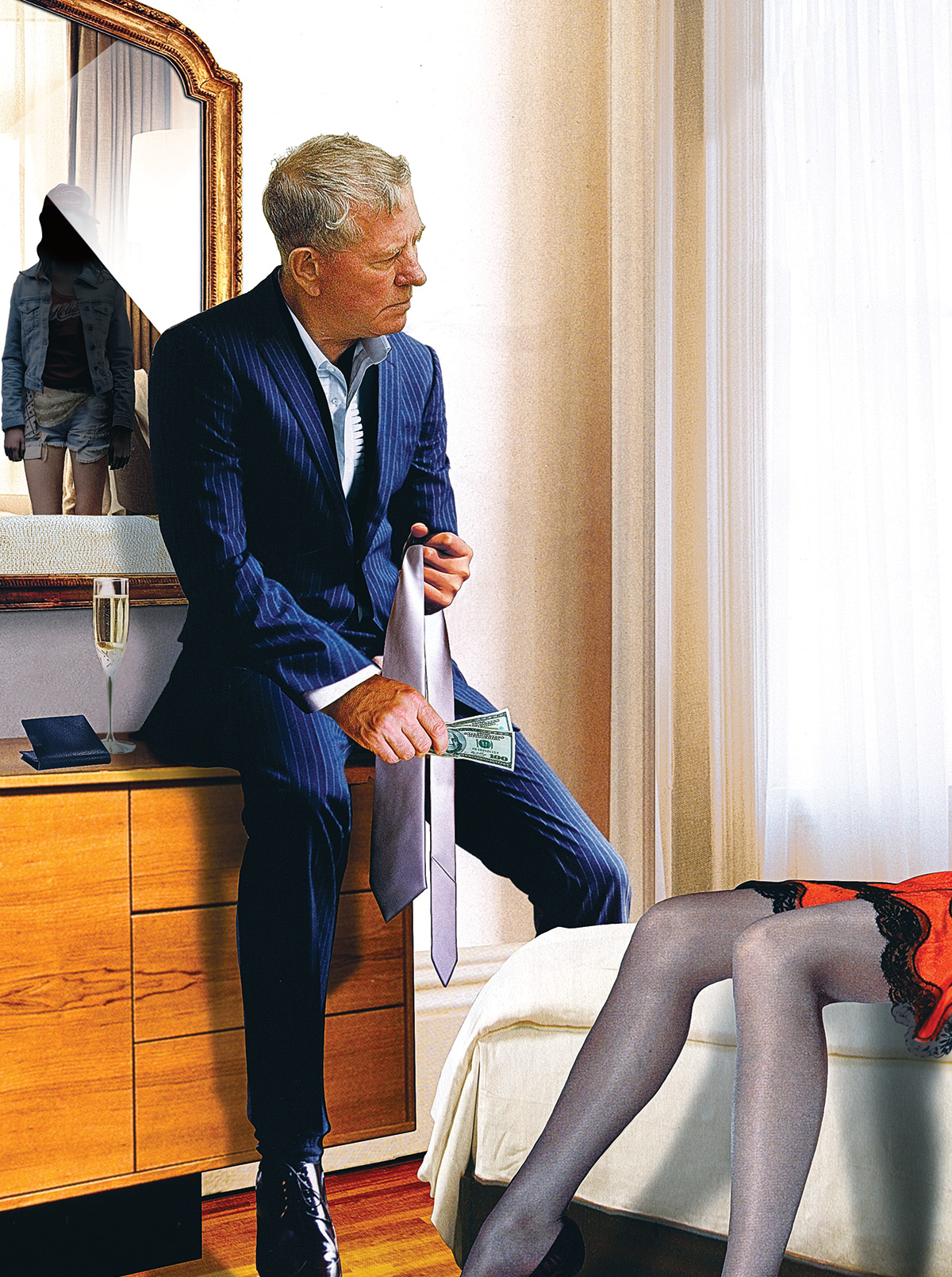

The 14-year-olf girl told police she visited the rich old man once a week. They had sex, and he gave her money. The man’s lawyer says the girl is telling malicious lies and no sex occurred: “To help somebody is not a crime.” / Illustration by Eddie Guy

He was drawn to flash, and a little bit of danger, perhaps not so uncharacteristic for a man who made a living in luxury real estate. There was the boat, a sleek 47-foot cigarette model, the sports cars, including a Ferrari and a Jaguar, the private helicopter. He told the girl he’d fly her to Martha’s Vineyard in that helicopter. He said he had to be very careful with her because she was so young.

They first met in the summer of 2009. He was somewhere around 70. She was 14. She went to his condo, she later told police, on something of a pretense, invited by a girl she knew simply as Kookie.

“You just have to watch,” said Kookie, a 19-year-old aspiring nanny who said she planned to have sex with the man. He was rich, one of the richest in Quincy, and he would give them money.

And so, as the girl would later tell police while laying out her version of events, she and Kookie took a cab to his condo in Marina Bay, the kind of luxury development that attracted athletes and high rollers, and judging from the place — a sprawling duplex with a Jacuzzi in the bedroom, mirrors that covered the walls and ceiling, and a skyline view of Boston — the man fit right in. The girl stood at the corner of the bed as Kookie and the man removed their clothes and put them on the floor. On the television, the girl could hear newscasters prattling on about earthquakes in California. Watching the two of them have sex, as she had been instructed to do, was awkward. At some point, the girl later told police, he called her over. He wanted her to have sex with Kookie while he watched. He also wanted to have sex with her.

She was scared — mostly, she later told police, because this was not the plan she and Kookie had discussed, but also because he was so old. “It’s okay,” he told her. He didn’t force her. She didn’t say no. According to police, Kookie held her hand, the older girl giving the younger a look as if to say, “It will all be over soon.” And it was. He ejaculated on her shirt, which she later threw away. Then he put on his pants, walked to the bathroom, and returned with $200 in cash for each of them.

According to a police affidavit based on an interview with the girl, she went back to 1001 Marina Drive about once a week after that — sometimes more, sometimes less, but never with Kookie. The man never used a condom. Each time, he would give her money from a black wallet — anywhere from $70 to $230. He never talked about why he was giving her the money — “that’s just how it always was,” she told police — and no matter how much he gave her, she would not complain, even if she was disappointed.

The man’s lawyer denies all of the allegations, and characterizes her detailed descriptions of repeated sexual encounters with his client as complete works of fiction.

The man, the girl admitted in her interview with police, was not unkind. He’d take her out to restaurants in Marina Bay. Once, when she’d run away from home, he gave her $500, and then $500 more. He said she was welcome to stay at his place whenever she liked, though she never took him up on the offer. He let her use his credit card to shop online, and she’d spend as much as $1,500 at a time, not as compensation, but because, she said, William O’Connell, the powerful developer who’d helped remake the town of Quincy, simply “wanted to take care of her.”

As the clock neared midnight on December 12, 2009, Joseph Fasano and Jennifer Bynarowicz were headed home to Quincy. They had spent the night out in Milton, where they’d been celebrating the birthday of Fasano’s mother. The two had been dating for a while, and lived together in a Quincy condo rented by Bynarowicz, a pretty 34-year-old. Fasano, 30, was a Milton firefighter and former Marine who’d served in Pakistan and Afghanistan. He had a wide face, a thick neck, and a bit of a dark side.

After a drink or two at the Dorchester bar Peggy O’Neil’s and two stops for gas and cigarettes, Fasano drove Bynarowicz’s Jeep Grand Cherokee along Hancock Street in Quincy, nearing home. As he approached the intersection with Commander Shea Boulevard, a dark-colored Porsche cut in front of him; Fasano later told police that he responded by tailgating the car until the driver of the Porsche suddenly slammed on his brakes and stopped right there, in the middle of Commander Shea.

Fasano pulled over and got out to confront the driver. He’d had a few drinks that night and was the kind of guy who was easily agitated, anyway. Bynarowicz, who stayed in the Jeep, watched as the driver of the Porsche also stepped out of his car. He was a white man wearing a black knit cap. Within seconds, she later told police, she heard a popping sound and saw the Porsche speed away. She got out of her Jeep, found Fasano lying in the street, and screamed. He was bleeding from his abdomen. “I’ve been shot,” he said. Police arrived to find Fasano being treated by EMTs, Bynarowicz hysterical, and cocaine and a couple hundred dollars sitting on the floor of the Jeep. According to an incident report later filed in court, when police asked Fasano if the shooting had anything to do with the drugs and the cash, he remained silent. They didn’t press. They thought he was dying.

It didn’t take long for the cops to track down the driver of the Porsche. A camera at Central Ave. Auto Service just down the street captured the car leaving the scene of the shooting and heading in the direction of Marina Bay, less than two miles away. Security cameras in the garage at 2001 Marina Bay had filmed a dark Porsche pulling into space number 20, registered to Robert O’Connell, the 40-year-old nephew of William O’Connell. The building concierge confirmed the car belonged to Robert and identified him as the man shown on the garage video exiting the car.

A quick police check revealed that Robert had a license to carry firearms, and owned a total of four guns, including two Smith & Wesson .45-caliber handguns. A .45-caliber shell casing had been recovered at the scene. Three days after the shooting, Robert turned himself in and gave police permission to search his car. They discovered gunpowder residue as well as a can of triple-action defense spray. At his condo they found the two Smith & Wessons and ammunition that matched the bullet doctors had removed from Joseph Fasano’s upper abdomen at Boston Medical Center. Fasano, who underwent multiple surgeries, remained in the hospital for nearly a week.

Before tracking down Robert, the police had labeled the whole thing a random act of road rage. “I would say this is probably fairly common,” Jeffrey Burrell, a Quincy police lieutenant, told reporters the day after the shooting. “This seems to be the way people drive now.”

The rags-to-riches ascent of William O’Connell and younger brother Peter has become something of a South Shore legend. They came from modest means — their dad was a milkman and their mom worked nights at a factory — and bought their first piece of land in 1958 with $450 that Peter earned from selling newspapers at Quincy’s Fore River Shipyard. In 1969, when William was 30 and Peter 26, the pair cofounded their development company. Their first project was a six-unit apartment building on that original lot.

Over the years, Peter and William O’Connell worked tirelessly and equally hard to class up Quincy, the geographic and socioeconomic pit stop between Dorchester and Braintree. O’Connell Management Company, which in later years grew to include Peter’s sons, Thomas and Robert, developed dozens of high-profile residential and office buildings, including the World Trade Center in Boston; Quincy’s Louisburg Square South; the nationally recognized Granite Links Golf Club in Quincy; and additional properties in Colorado, Florida, and overseas.

The brothers’ signature project, though, was Marina Bay in Quincy, which features restaurants, shops, offices, and the region’s largest private marina. First developed in the ’80s, the place became known as a celebrity haven, the “Nantucket of Boston” — home to boldface residents such as Tom Brady, Chet Curtis, and a host of other media types and athletes, some of whom became close friends with the O’Connells. During Peter’s ill-fated 1989 run for Quincy mayor, his personal friend Ted Kennedy was out there stumping for him. Former Cardinal Bernard Law was reportedly a passenger on an O’Connell family private plane.

Few high-end real estate developers get into the business to make friends, and it’s true that many O’Connell projects have faced opposition from politicians, environmentalists, and various other groups, but the family has for the most part been liked and respected. “They helped build Quincy,” Peter Forman, South Shore Chamber of Commerce president and CEO, has said. “[The family is] very much a part of the community.” As kids, the brothers passed out campaign fliers for Arthur Tobin, a former Quincy mayor who now serves as clerk magistrate of the city’s district court. Former Quincy Mayor Walter Hannon Jr. partnered with the O’Connells in the development of Granite Links. And over the years, the O’Connells have given thousands of dollars to local candidates, including former U.S. Representative William Delahunt (who lives at Marina Bay), former state Treasurer Tim Cahill, and current Norfolk County District Attorney Michael Morrissey. The brothers, it seems, were strategic in their donations; their close ties to so many local leaders didn’t exactly hurt their development projects.

While Peter was the conservative brother, the one with a stable family life and a name that tended to appear in the papers only in connection with the family’s various projects, William was never a man people might describe as upstanding. He was a workaholic, but high-profile trouble seemed to swirl around him. In 1990, his 29-year-old son, Matthew “Ky” O’Connell, was convicted of second-degree murder for killing 22-year-old Julie Hamilton, a friend of a friend. Her body was found in a shallow grave near the house Ky shared with his mother, Mary McLain. During the trial, McLain testified that as a child Ky had frequently set fires and ripped apart his teddy bears. The night of the murder, she remembered, he’d woken her three times to ask where she kept a pick and shovel. Ky was sentenced to life in prison, but was eventually transferred to Bridgewater State Hospital, a facility for convicts in need of psychiatric care.

Then, in 2002, William was charged in the accidental death of his longtime best friend, Bill Sanderson, a South Shore real estate agent. During a Fourth of July celebration, Sanderson was struck by the propeller of William’s boat, which had been anchored illegally in shallow water off Martha’s Vineyard. Peter O’Connell rode to the hospital with Sanderson, holding the dying man. William O’Connell left the scene, later claiming he was simply looking for a safe place to dock, but once on land he refused to take a police Breathalyzer test. Sanderson’s widow, Donna, asked the judge for leniency. William was put on six months’ pretrial probation on the negligent homicide charge and received a 120-day suspension of his driver’s license, and the case was dismissed.

William O’Connell was regarded in some circles as a womanizer and party boy with a destructive nature. Six years later he was involved in a private-helicopter crash with two New Hampshire women in their early twenties.

And so by the time news of William’s most recent troubles surfaced in May of this year, people were well used to hearing about his assorted transgressions. But even by the standards of his checkered past, the allegations in his latest mogul-gone-wild episode — charges of child rape and drug trafficking — were shocking.