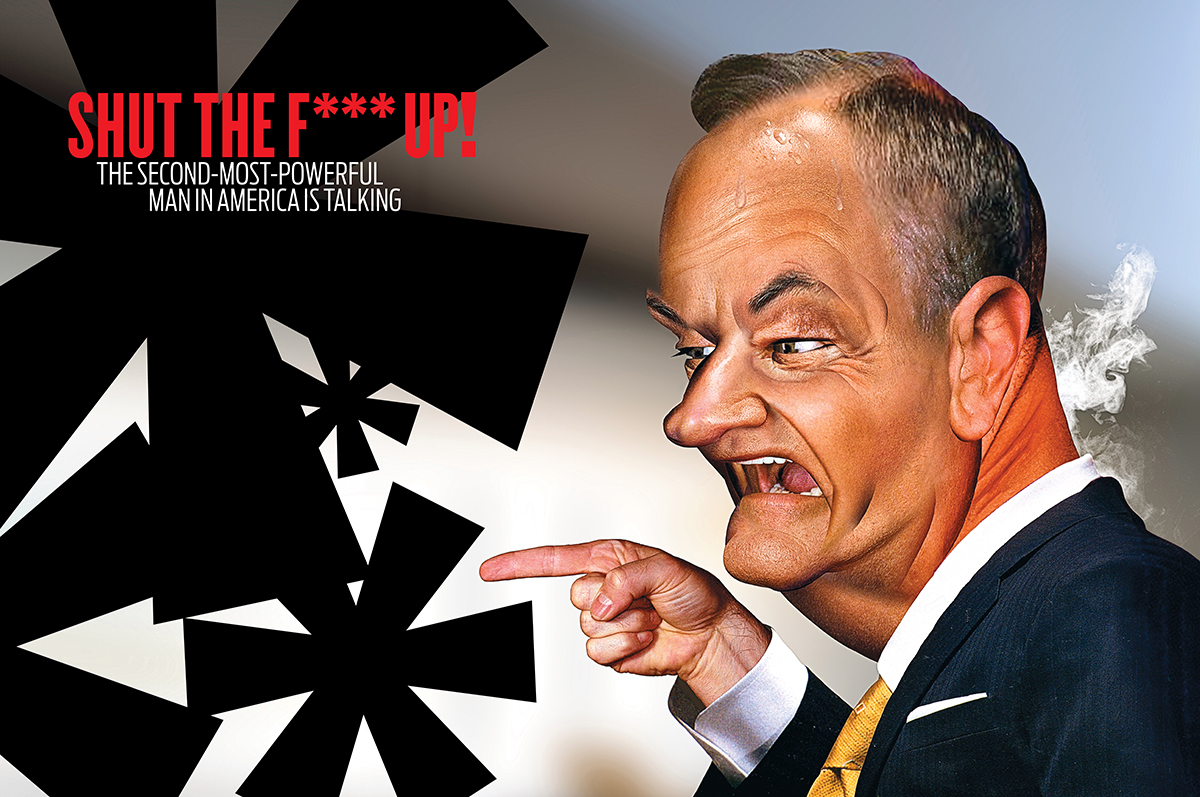

Shut the F*** Up! The Second-Most-Powerful Man in America is Talking

Illustration by Eddie Guy

Narcissistic Behavior: “Preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love.”

Bill O’Reilly had a pretty good year in 2011. The O’Reilly Factor, his show on Fox, was once again the number one program in cable news, regularly crushing the competition on MSNBC and CNN. His book about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Killing Lincoln, made the New York Times bestseller list. And he earned a reported $10 million, which isn’t too shabby for a former Boston TV personality.

Of course, even in the best of years, everyone’s bound to have a few missteps. In August, the website Gawker broke a story that an enraged O’Reilly had pulled strings to get New York’s Nassau County Police Department to investigate an officer he suspected of having a relationship with his estranged wife. In October, when O’Reilly sent a “care package” of copies of his book Pinheads and Patriots to American soldiers stationed at an outpost in Afghanistan, they burned the lot in a trash barrel and posted photos of it online. Then, in November, the bookstore at Ford’s Theatre — the site of Lincoln’s murder — banned Killing Lincoln because of its inaccuracies. Ouch.

But O’Reilly’s lowlight last year was surely this quote, which appeared in a September profile of him in Newsweek:

“I have more power than anybody other than the president, in the sense that I can get things changed, quickly.”

You want to know something? There are plenty of other people on TV, from Oprah to Alex Trebek, who probably think something like this occasionally. But it really is a pretty amazing thing for a cable TV personality to say. Out loud. To a magazine.

Seriously, the second-most-powerful person? Never mind Joe Biden or John Boehner, or even O’Reilly’s bosses Roger Ailes and Rupert Murdoch: There are dozens of people who wouldn’t even crack a top-100 “most powerful” list, but still have more juice than Bill O’Reilly. Like, say, Matt Lauer, Simon Cowell, Jon Stewart, or Maury Povich. O’Reilly got an interview with President Obama? So did an elementary school kid from Florida. I mean, he can’t even win the War on Christmas! People were still saying “Happy Holidays” at the Chestnut Hill mall this year, so how powerful can he be?

That quote did, however, get me thinking about what the hell would cause someone to say something so obviously absurd. Was it just ego? I mean, clearly, we already knew that O’Reilly has an ego — from shouting, “Shut up” at guests on his show to his network’s claim that the pope pays attention to his opinion.

Listen, I know what it’s like to have a healthy ego. I, too, was famous for a time. At least a little bit. As the co-anchor of the popular ’90s tabloid news show Hard Copy, I ran in some of the very same circles as O’Reilly. I flew on private planes and interviewed actors, athletes, and politicians. In between signing autographs, I could clap my hands and fruit would be delivered. And I did clap them. It was amazing. And it was fun, and yes, it goes to your head.

But a claim like O’Reilly’s goes way beyond egotistical — it seems to me to veer dangerously into the pathological. As I thought about it more, I began to seriously wonder if he wasn’t merely your garden-variety baby-boomer narcissist but somebody afflicted with a full-on case of what’s known as narcissistic personality disorder. So I dug out the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV — the chief tool psychiatrists and psychologists use to diagnose mental illness in their patients — to learn more. The chief characteristic of NPD, it turns out, is “a grandiose sense of self, a serious miscalculation of one’s abilities and potential that is often accompanied by fantasies of greatness.”

Hmm. Sounds like somebody we know. I read on. To receive an NPD diagnosis, individuals must exhibit at least five out of nine classic narcissistic behaviors, things like a lack of empathy and a need for admiration. Check and check. Interest piqued, I was ready for more. Could I, simply by rummaging through O’Reilly’s very public actions and antics, try to “diagnose” him with NPD? I’d cue up YouTube, talk to some psychiatrists, interview old coworkers. Didn’t seem too hard at all.

As I began the process, though, I did know one thing: Even if O’Reilly isn’t the second-most-powerful man in America, he certainly wields some influence: After all, he did get me fired once.

Narcissistic Behavior: “Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g., exaggerates achievements and talents, expects to be recognized as superior without commensurate achievements).”

As I set about plumbing the very depths of Bill O’Reilly’s ego, my first call is to Paul Meier, a psychiatrist and the coauthor of You Might Be a Narcissist If…. The truth is that in this age of social media and reality television, it can be difficult to tell the difference between a little egotism and clinically significant narcissism. “We all have a few narcissistic tendencies, unless we are perfect,” Meier tells me. “And if you think you are perfect, well, you’re a narcissist!” Where it starts to become a problem, he says, is when we see “a pattern of deviant or abnormal behavior that the person doesn’t change, even though it causes emotional upsets and trouble with other people at work and in personal relationships.”

It’s unethical for a psychologist or psychiatrist to make even a tentative diagnosis of someone they’ve never met or treated, so I don’t ask Meier to weigh in on O’Reilly specifically. But before we get off the phone, Meier does offer some helpful advice: People with severe personality disorders display traits of it rather early in life.

That got me thinking about O’Reilly’s 2008 autobiography, which is called A Bold Fresh Piece of Humanity. Where did he come up with that title? It’s apparently something a nun once used to describe him. When he was eight years old.

Still, what’s one book title when you’re trying to take the measure of a man? If I was going to get to the bottom of Bill O’Reilly’s problems, I was going to need more. So I called up Rory O’Connor, who was a year behind O’Reilly at Chaminade High School on Long Island in the 1960s. O’Connor later went on to work with O’Reilly at WCVB Channel 5, one of O’Reilly’s early broadcasting jobs. Today, O’Connor is a filmmaker and the coauthor of Shock Jocks: Hate Speech and Talk Radio, which examines radio hosts like Rush Limbaugh, Don Imus, and O’Reilly. O’Connor says his old colleague and classmate was a “pompous jerk.” When I told him about O’Reilly’s “second-most-powerful” quote, O’Connor replied, “I am only surprised that he thinks he is only the second. He is definitely delusional.”

And really, it’s not even necessary to go beyond O’Reilly’s own words to find more prime examples of delusion. In 2007 author Marvin Kitman published The Man Who Would Not Shut Up, an authorized biography of O’Reilly. In the book, O’Reilly tells Kitman that he was a richly gifted but woefully underappreciated high school football player. O’Reilly, who made the team his senior year but was a bench warmer, says he could kick field goals from 45 yards, punt 60 yards, and deliver 80-yard strikes with his passing arm. The reason he couldn’t get on the field during games: The equipment manager claimed there were no more pads left.

Narcissistic Behavior: “Believes that he or she is ‘special’ and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people (or institutions).”

In case it’s not obvious by now, I can get a little neurotic about whether, I, too, might suffer from some kind of narcissism disorder. As I said, a taste of fame can do weird things to you. So learning that clinical narcissism tends to show up early made me feel a little better. When I was a kid, I had no delusions of grandeur. I was a nerd, and I knew it. Horn-rimmed glasses, zits, advanced math class, and barely third-string on the football team. When I became famous, it caught me by surprise. And it turned out to be just a phase.