Out of this World

From the red barn where glass artist Josh Simpson works, you can see the Berkshire foothills stretching out to the west. His Shelburne property is pastoral, with the faint soundtrack of the wind.

Inside the barn, though, it’s loud. Here, 62-year-old Simpson and four fellow artisans are birthing planets — handblown glass spheres infused with intricate and colorful coral-like structures. They labor throughout the day to the hiss of three furnaces and the intermittent pssst! of a blowtorch.

“You can imagine that you’re an astronaut looking down,” Simpson says of his complex marble-inspired creations. “Sometimes you can imagine that you’re a scuba diver swimming amongst some little world.”

When Simpson started making the spheres in 1976, the year he moved into his Shelburne home and studio, few were buying his art glass. “I remember thinking, If I want my work to be in museums someday, I should hide it around the world so maybe archaeologists will find it and wonder what it was for,” he says.

Fortunately, others have done it for him. Simpson’s glass planets have traveled from western Massachusetts to destinations around the globe. One sits near explorer Ernest Shackleton’s grave in Antarctica; another was left in a 3,000-foot-deep trench in the Atlantic Ocean by researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. His creations are nestled in stone walls in New England, buried in the Madagascar rainforest, and hidden at Camp Leatherneck in Afghanistan. And thousands more dot the map, says Simpson, who calls his glass diaspora the Infinity Project.

Simpson’s works have even traveled celestially, thanks to astronaut Catherine “Cady” Coleman, his wife of 14 years. She’s been to space three times, most recently on a five-month mission to the International Space Station, and has taken several planets with her before bringing them safely back home. “It’s definitely a career-limiting move to throw stuff outside the shuttle,” jokes Simpson, who has been fascinated by astronauts and space exploration ever since he was a kid.

Back on Earth, his delicate work, which also includes vases, platters, bowls, and tumblers, is now part of the permanent collections at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, among many others. And in 2010, he showed locally at the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton and the Sandwich Glass Museum. His art can be purchased on his website.

“[Being a glass artist is] almost like eating the icing off the cake every day,” he says. “What’s really held my attention for so long is that it is so crazy-difficult to do. [Glass] has no respect for you as an artist; it’s unemotional, and all it wants to do is drip on the ground or burn you.”

Josh Simpson holds a planet-in-progress inside his Berkshire studio.

.jpg)

Photograph by Pat Piasecki

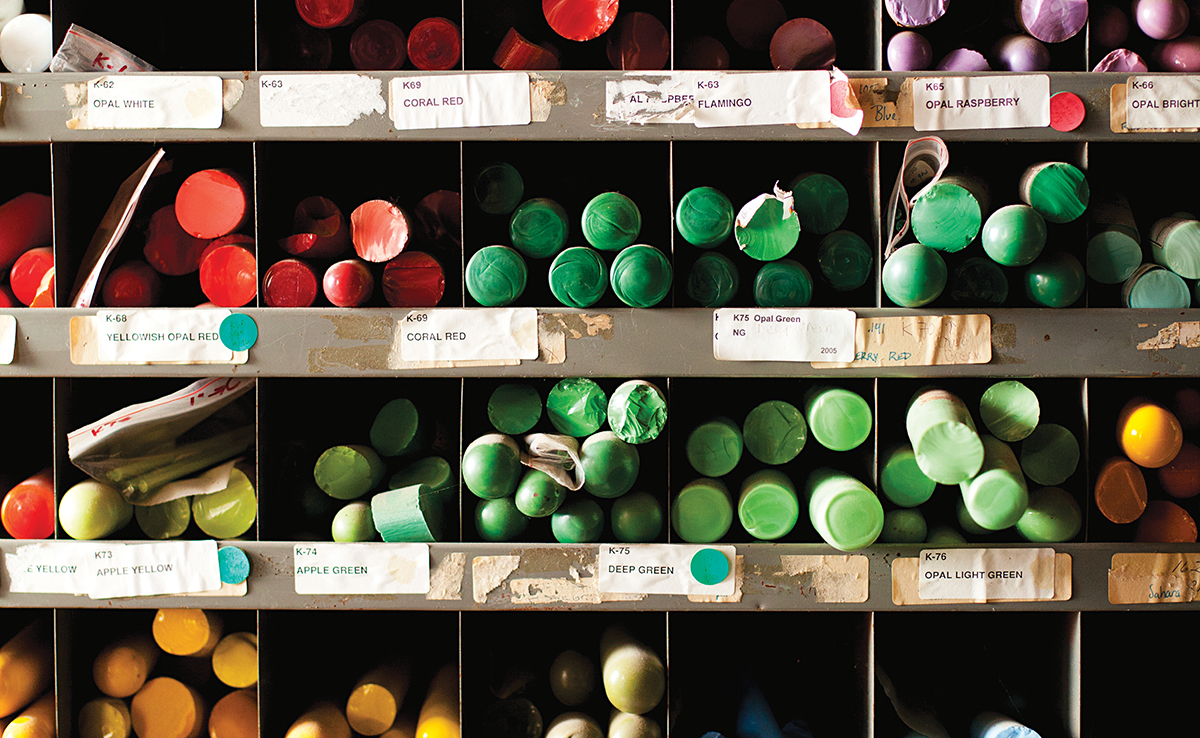

Hundreds of colored glass rods are fused together, stretched, and then cut into tiny pieces to be melted onto the surface of his decorative orbs.

Simpson bought his Shelburne home and studio in 1976.

Optic forms create surface textures that trap air bubbles inside of the molten glass.

A finished creation.

A vibrant array of glass rods.

Simpson adds layers of glass, metallic silver, and various colored details to a piece.

Simpson uses metal tools to shape the molten glass, and crushed colored glass pieces to create tiny patterns in the planets.

Delicate gold leaf is another material that Simpson and his team use to adorn their creations.

The heat from a hydrogen torch smooths a glass planet into a perfect crystal sphere.