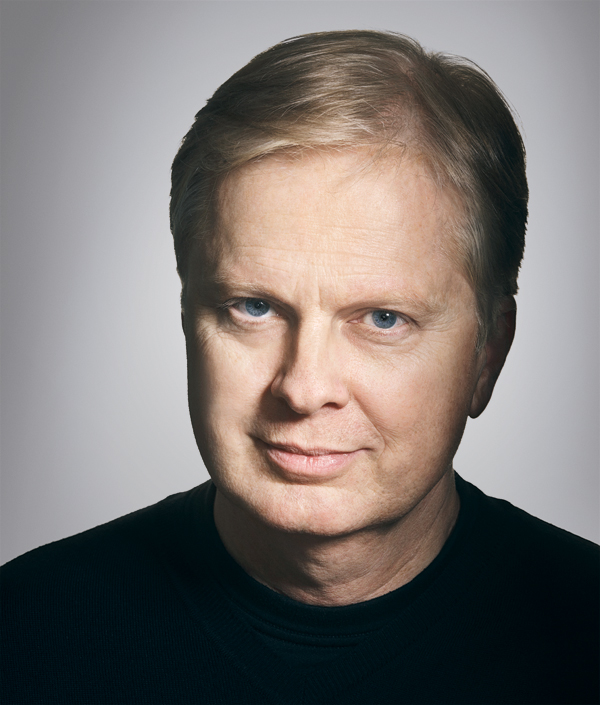

Tom Ashbrook: Point Man

Photos by Adam Detour

It isn’t easy to speak cogently and think at the same time, but Tom Ashbrook is very good at it, and he is sometimes impatient when guests on his radio show, On Point, are not.

On a Thursday morning in December, during a segment titled “What to Do About Climate Change?” he challenged Vicki Arroyo, the executive director of Georgetown University’s Climate Center, to say which policy measures might slow global warming, and how those measures might change contemporary society. Arroyo suggested tightening both emissions standards and the rules on coal-burning power plants, and then seemed to argue that doing so would be mostly painless. Ashbrook grew incredulous.

During shows, Ashbrook spends much of his time scribbling notes or circling ones that he has already taken. The desk he uses while on air, in Studio 3 at WBUR, is covered by an expansive, ever-shifting puzzle of paper—photocopies of articles, excerpts from books, studies—that he refers to throughout the show. But when Ashbrook wants to interject, he raises one or both hands in the air. If he is in the studio alone, which is the case most of the time, it looks like he’s gesturing for the attention of one of the On Point producers, who are stationed 10 feet away on the other side of a double-thick wall of glass. The first time I saw him do this, during a segment in late November, I thought something had gone wrong. But Ashbrook was in fact simply preparing for what was to come next, a bit like an orchestra conductor between movements of a symphony, only with himself as both conductor and orchestra. Once he begins speaking, his hands drift back to the table, and he resumes fidgeting.

“But what about in our daily lives?” he asked Arroyo. “If we’re gonna get on top of this, are we gonna have to live different lives than we live now, in some fundamental ways? Or what?”

“Technology is part of it,” Arroyo said, “and so the car you drive now might be different than the car you—”

“We got that. Yup.”

“—otherwise would drive. But you know, if we change where the power comes from, do you know where the electrons in your own home come from? I don’t think necessarily—”

“Okay, that’s two, we got that. There’s your power plants. Take us on.”

After some hemming and explaining, Arroyo arrived at a tax on carbon emissions, though it was Ashbrook who finally used the phrase “carbon tax.” Ashbrook does not relish discussing his political views, but he told me later that global warming is an issue of importance to him. He was anxious to move the hour beyond the usual talking points. Intellectually, he is a man of action, and he was bored.

Anybody who listens to On Point will eventually confront the fact that Ashbrook soaks up an unusually large volume of information. He seems able to talk intelligently about almost anything. “There are other talk-show hosts, they do a great job,” says Jack Beatty, On Point’s news analyst. “But man, his capacity!” Graham Allison, of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and a past guest on the show, told me that Ashbrook’s command of international affairs occasionally outdoes his own. Driving one day in November, I caught a snippet of a segment on the film adaptation of Anna Karenina, during which Ashbrook delivered a relatable summary of Tolstoy’s ideas about fidelity and happiness, apparently off the cuff and without sounding pretentious. That was in hour two. In hour one, he’d looked at the implications of several recent leadership changes in China’s ruling politburo. This is what he does five days a week, 50 weeks a year. An hour on the Congo that segues into an hour on Dolly Parton. Assisted suicide followed by the super wealthy. In just one week this past December, Ashbrook did shows on drones, the fiscal cliff, the American Revolution, the recently deceased jazz pianist Dave Brubeck, and domestic violence and the NFL. Since 2001, he has hosted more than 5,000 hours of radio.

Ashbrook is blunter than most NPR hosts. He frequently interrupts his guests to summarize what they are saying and then to pose another question. At times this lends the impression that he is answering his own questions, but more often than not it makes for potent, urgent conversation. (He is noticeably gentler with callers.) One former On Point producer told me that Ashbrook’s ability to host at the same speed that listeners hear—to anticipate questions and challenges, and then ask them as they arise in listeners’ minds—is as good as that of anyone he has worked with in radio. Ashbrook believes this quality is deeply satisfying for his audience.

Oddly, when On Point launched in 2001, six days after the 9/11 attacks, originally as special coverage for NPR, Ashbrook had never worked in radio. In fact, he had fled news altogether a half decade earlier, after a distinguished career at the Globe. When WBUR called, looking for a host, he was off trying to raise venture capital for a tech startup and was writing a novel. It was not obvious that he would be a good host, or that he even wanted to be a journalist again.