Does Moderna Therapeutics Have the NEXT Next Big Thing?

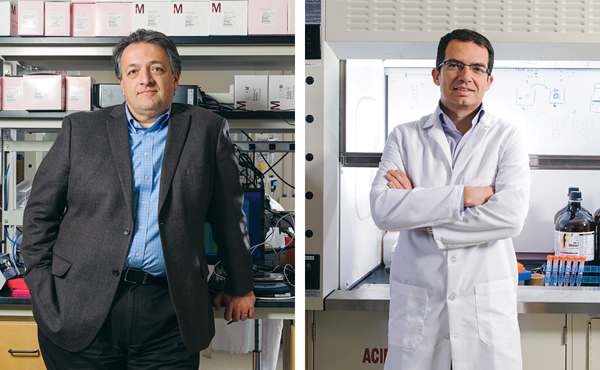

Left: The Venture Capitalist, Noubar Afeyan: A biochemical engineer and the head of the Cambridge-based Flagship Ventures, Afeyan jumped at the chance to get Moderna up and running. “In the realm of therapeutics,” he says, “this is the most promising thing I have ever seen.” Right: The CEO, Stephane Bancel: Bancel left behind a job as the head of a biotech giant to join Moderna, a startup with no products and only one other employee. “I knew I’d never forgive myself,” he says, “if I’d turned down the chance to run the next Genentech.”

That night, on his drive home to Lexington, Afeyan excitedly began to envision the expansive landscape in which Rossi’s technology could be applied. At the same time, he did what he always does when mulling over a new investment: He began to look for ways in which the idea wouldn’t work. In the case of Rossi’s idea, however, nothing seemed to apply, and by the time he got home, he was convinced that Rossi had stumbled onto something huge. He wanted in. “In the realm of therapeutics,” he told me later, “this is the most promising thing I have ever seen.”

Two weeks later, Rossi met with Ken Chien, a physician-researcher at Harvard and the Karolinska Institute. After the meeting, Rossi and Chien, who is famous for his work on heart stem cells, ran some experiments and found that heart cells avidly took up Rossi’s modified mRNA and began expressing proteins. This was a highly promising development. For years, Chien had been trying to figure out how to effectively regenerate heart muscle and vessels damaged by a heart attack, and Rossi’s technology suddenly offered him a potential solution. He, too, wanted in.

A core team was now in place. With the backing of Flagship VentureLabs, Rossi, Langer, Afeyan, and Chien banded together and founded Moderna, with Tim Springer as one of the initial investors and board members. In September 2010, Rossi published a paper documenting his breakthrough, and within days Flagship announced the existence of the company. Behind the scenes, already in stealth mode, the company began looking for a CEO.

In early 2011, Stephane Bancel was running the French diagnostics company BioMérieux, the executive offices of which were in Kendall Square, and was starting to think about what was next. At the time, BioMérieux was doing $2 billion in annual sales, and Bancel was being headhunted to run companies two and three times its size. Afeyan himself had tried to hire him to run a startup a couple of times, but Bancel had always turned him down. “I told him I was willing to take a career risk by working on something that might not work,” Bancel recalls about those early conversations with Afeyan. “But it would have to be something that, if it worked, would change the world.”

So in February 2011, when Afeyan called Bancel and asked him to stop by his office after work one evening, Bancel knew Afeyan had to have something interesting. It was about 6 p.m. by the time Bancel made it over to Flagship, where Afeyan delivered his pitch: He wanted Bancel to work on a startup that had so far hired only a single staff scientist, and had conducted just one mouse trial. Nevertheless, he told Bancel, the stakes were extremely high. If the technology proved successful in human beings, it would take Moderna weeks, not years, to make a new product. And there was more: Because the company would always be making the same thing—mRNA—the only thing that would ever have to change was the protein for which the mRNA would be coded. That meant that the company could make all of its products in the same plant—and that plant would cost a tenth of a typical one.

Afeyan also hit altruistic notes that he knew would appeal to Bancel. Because of its versatility and the small scale of its operations, Moderna would be able to go after the rare and tragic “orphan” diseases, those that most Big Pharma companies simply don’t pursue because there just aren’t enough patients in need of treatment to make the production of drugs for them financially worthwhile. Moderna, in other words, could save lives. Children’s lives.

Then Afeyan appealed to the capitalist in Bancel. Because Moderna would not be making drugs, he explained, but instead would be engineering the mRNA to code for those drugs, it could completely bypass all protections and compete immediately with patented drugs already on the market. And because the Moderna technology allows proteins to be made inside cells—something currently impossible with other protein-based therapeutics—it would be able to do everything current drugs do and many other things that they do not. Moreover, because the technology doesn’t touch DNA, it avoids the cancer risks traditionally associated with gene therapy. One other thought may have also occurred to Bancel as he listened to Afeyan: Given that Moderna’s technology isn’t a one-time fix, like gene therapy, patients would have to keep buying the company’s products.

Bancel left the meeting with his head spinning at the scientific and business potential of Moderna. In the weeks that followed, he interviewed the others involved with the company, and then took his wife out to dinner at Bin 26, near their Beacon Hill home. Over wine they talked through the offer. His wife asked him if he liked the science and the people he’d be working with. Bancel said he did. She asked if he could imagine a better way of using the next 10 years of his life. Bancel said he couldn’t—but worried out loud about the odds of failure. “She told me to stop being French,” he recalls, “and not to be afraid of taking a risk.” In the end, he decided to take the job. “I knew I’d never forgive myself,” he says, “if I’d turned down the chance to run the next Genentech.” The next day, he called Afeyan and told him he was in.

When Bancel broke the news of his departure to the board of directors at BioMérieux, he says, they reacted with complete confusion. Why on earth would he resign from such a powerful position to be employee number two at a startup with no products and only a single mouse experiment behind it? They tried to get him to stay, he says. But by then his mind was already elsewhere.