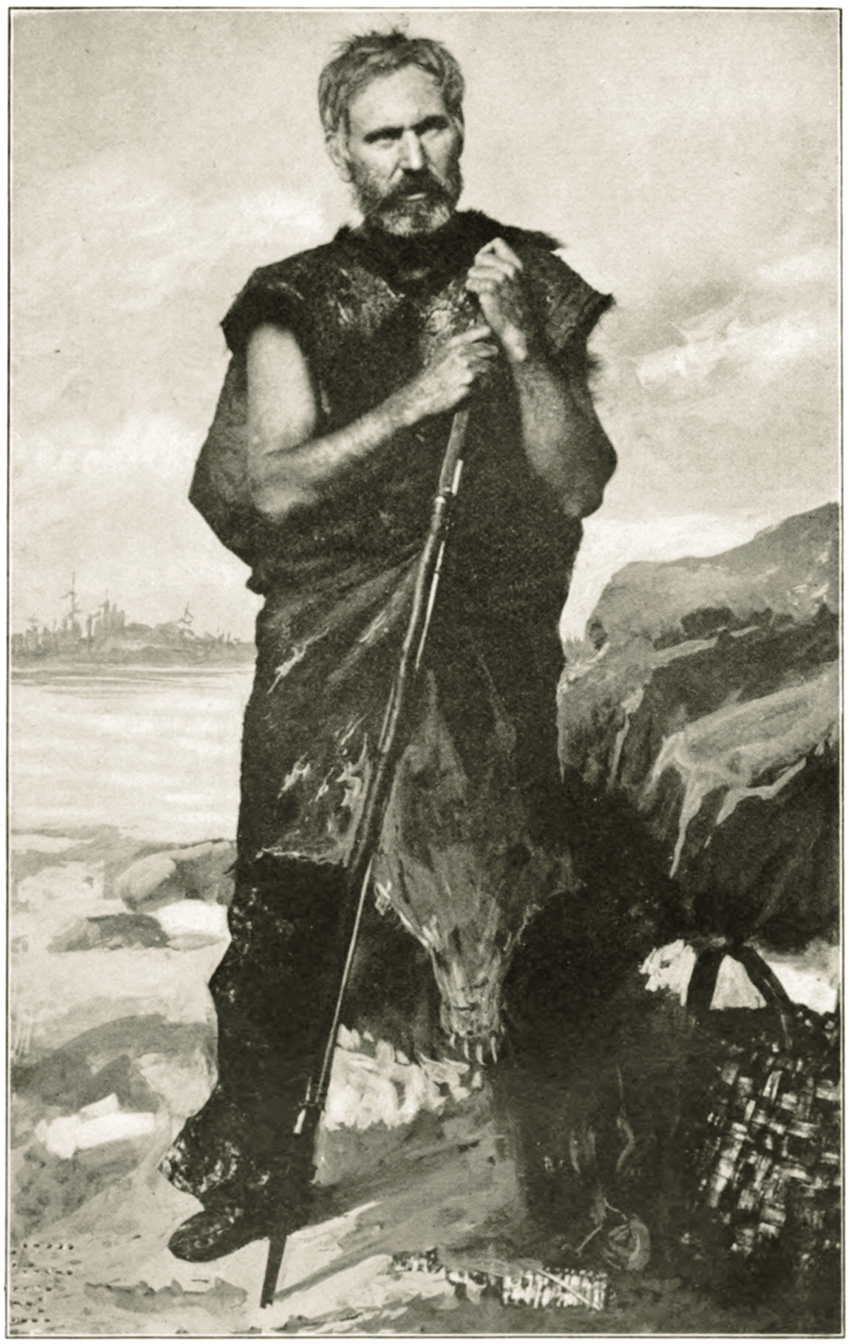

Naked Joe

Knowles in a bearskin robe on October 4, the day he reemerged from the wild.

The expedition began on a drizzly August morning, in a sort of no-man’s land outside tiny Eustis, Maine. The spot was some 30 miles removed from the nearest rail line, just north of Rangeley Lake, and east of the Quebec border. Knowles showed up at his starting point, the head of the Spencer Trail, wearing a brown suit and a necktie. A gaggle of reporters and hunting guides circled him.

Knowles stripped to his jockstrap. Someone handed him a smoke, cracking, “Here’s your last cigarette.” Knowles savored a few meditative drags. Then he tossed the butt on the ground, cried, “See you later, boys!,” and set off over a small hill named Bear Mountain, moving toward Spencer Lake, 3 or 4 miles away. As soon as he lost sight of his public, he lofted the jockstrap into the brush—so that he could enjoy, as he would later put it in one of his birch-bark dispatches, “the full freedom of the life I was to lead.”

On his own, Knowles kept hiking. It was raining. In bare feet, he slipped in the mud, but still he trudged on over the flank of Bear Mountain. Eventually, he spied a deer. “She looked good to me,” he wrote, “and for the first time in my life I envied a deer her hide. I could not help thinking what a fine pair of chaps her hide would make and how good a strip of smoked venison would taste a little later. There before me was food and protection, food that millionaires would envy and clothing that would outwear the most costly suit the tailor could supply.” Knowles resisted the temptation to kill the deer, deciding to live within the game laws of Maine. He was hungry, wet, and cold, and also still a bit thrilled and agitated about being out there sans jockstrap. He could not sleep. What to do? He tossed off a few pull-ups. “On a strong spruce limb I drew myself up and down, trying to see how many times I could touch my chin to the limb. When I got tired of this, I would run around under the trees for a while.”

If Knowles made himself sound like Tarzan, it was perhaps intentional. One of the most popular stories in Knowles’s day was Tarzan of the Apes, an Edgar Rice Burroughs novella. Published in 1912 in the pulp magazine All-Story, it starred a wild boy who goes “swinging naked through primeval forests.” The story was such a hit that in 1914 it was bound into book form.

Pulp magazines (so named because they were published on cheap wood-pulp paper) represented a new literary form, born in 1896. They offered working-class Americans an escape into rousing tales of life in the wilderness. Bearing titles like Argosy, Cavalier, and the Thrill Book, they took cues from Jack London, whose bestselling novels, among them The Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906), saw burly men testing their mettle in the wild. They were also influenced by Teddy Roosevelt, who insisted that modern man needed to avoid “over-sentimentality” and “over-softness” while living in cities. “Unless we keep the barbarian virtue,” Roosevelt argued, “gaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.”

Both Knowles’s dispatches and the pulps represented a sharp departure from the pious nature writing that had prevailed in this country until about 1900, especially in New England. Thoreau had died in 1862, but at the turn of the century his heirs were still fixed on seeking wisdom, as opposed to adventure, in the outdoors. Boston’s principal hiking group at the time was the Appalachian Mountain Club, and its members, says Christine Woodside, the current editor of the AMC’s journal, Appalachia, “were often high-level academics, people from MIT or Harvard, who told themselves: ‘We are deep thinkers about the wilderness and what it does for our character.’ They’d come home and deliver academic papers or write journal articles.”

The editor of Appalachia from 1879 to 1919 was Charles Ernest Fay, a professor of modern languages at Tufts, and also an unabashed snob. In a 1905 Appalachia essay, “The Mountain as an Influence in Modern Life,” Fay dismissed country people as incapable of enjoying the splendors of nature. “The mountain dweller,” he wrote, “may even look upon the towering masses that surround him as so much waste land, as occupying space that might otherwise come under tillage.” Fay advocated for a superior species: the mountaineer, who, though he sees the mountain only rarely, loves it “for the grand anthem its forests sing to him, for the rich and varied gallery of Nature paintings that in sunshine and in storm, in the day-time and in the night season, it reveals to his eyes.”

Fay’s bald elitism had, of course, a long legacy in Boston. For most of the preceding century, the city had been lorded over by the Brahmins—the Quincys, the Cabots, the Lowells, the Lodges—who sequestered themselves on Beacon Hill and shored up their wealth as they championed high-minded cultural institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. By 1913, though, the city had changed. With a population of 670,000, it was home to more than 200,000 recent immigrants, most of them Irish and Italian. In 1914 it would elect as its mayor James Michael Curley, a Catholic born in Roxbury’s Irish ghetto. Curley was so beloved that he was reelected as mayor three times, even though he was twice imprisoned for fraud. He was not a restrained individual. Once, in attacking an allegedly communist WASP political foe, he said, “There is more Americanism in one half of Jim Curley’s ass than in that pink body of Tom Eliot.”

As a newspaperman with artistic ambitions, Knowles was, socially speaking, a notch above the factory workers, bakers, and dockhands who made up Curley’s core constituency, but he was still solidly ensconced in Boston’s rising underclass. A grade-school dropout, Knowles grew up in Wilton, Maine, a tiny town about 40 miles northwest of Augusta. His father was a disabled Civil War veteran. His mother supported the family’s four children by selling moccasins, as well as firewood and berries gathered in the forest. They were poor, and the subject of local ridicule. “The schollars poked fun at my homespuns,” he wrote in an unpublished memoir, “tore the patches off my clothes, and stole my lunch…. And to make a good job of it, they broke up the bread and threw the crumbs to the birds.”

As Knowles tells it, his father bullied him, too, and when he was 13, after a paternal beating, he ran away, lying about his age so that he could work aboard cargo ships and travel the world. Knowles would eventually visit Cuba, South America, the Mediterranean, China, and Japan. By the time he was 17, he’d enlisted in the U.S. Navy and had returned to Wilton with a tattoo of a young woman twirling a snake. On another teenage return home—a surprise visit made after two years at sea—he arrived with a bottle of whiskey, a gift for his dad. His father did not say a word and did not touch the bottle. “He just gave me a look,” Knowles wrote, “that was all. That hurt more than all the lickings he’d ever given me.”

As dawn broke on his second day in the woods, Knowles fashioned a basket out of birch bark and began gathering berries. He speared two trout, but a mink stole them. He tried to light a fire, but the woods were still damp from the rain, so he simply built a shack out of dead sticks, fir boughs, and moss, and lay down, naked and hungry, in the forest duff.

The next day, Knowles sewed himself some witch-grass leggings and constructed a dam across Little Spencer Stream, to channel fish into a trap. On his fourth morning, he built a fire and ate baked trout for breakfast.

Then the reports stopped. For 11 days, no birch-bark dispatches appeared. The Post milked this silence for drama, reporting that Maine woodsmen believed him injured. Meanwhile, the paper squeezed all sorts of entertaining side dramas out of the Knowles saga. One story, titled “Joe Knowles Blew His Way To Fame,” recounted the Nature Man’s naval career. Another piece was titled “Boston Hunters Admire Knowles’ ‘Cave Man’ Feat.”