Harvard Finds Evidence of a Colonial Boycott Hiding in Plain Sight

Image via the Houghton Library Blog

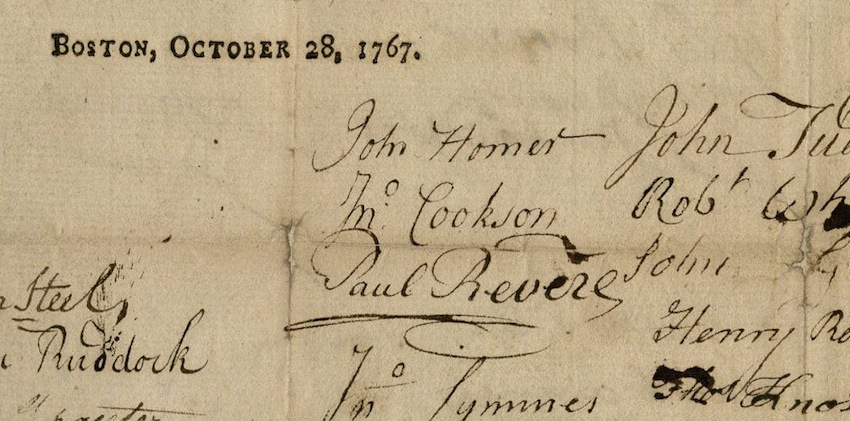

On October 28, 1767, Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss the Townshend Acts, a series of new taxes passed by the British Parliament, and decided they would produce and distribute several “subscription” papers, asking people to sign a pledge to boycott certain British imports. It would become one of several economic protests of British taxation in the years leading to the American Revolution (the Boston Tea Party perhaps most famous among them).

What happened after that meeting, though, wasn’t completely clear—How many Boston residents agreed to the boycott and who were they?—because researchers didn’t have the signatures. Then this past week, Harvard librarians discovered eight of the subscription papers hiding more or less where you might expect to find them … on the shelves of Harvard’s Houghton Library. Thanks to the rediscovery of a resource Harvard didn’t even know it had, historians can now pore over a list of 650 signatures to analyze just who was protesting British taxes in the tumultuous years leading up to the American Revolution.

“When Houghton opened in 1942 there was a big influx of collections of donations and things that were donated from other Harvard libraries, and so a lot of this stuff got sort of minimal cataloguing,” says John Overholt, curator of early modern books and manuscripts at Houghton. When those bare-bones records were digitized, some of the less well-documented ones couldn’t be automatically converted, which has required the librarians to make their way through a backlog over the years. That’s how Karen Nipps, Head of the Rare Book Cataloging Team, stumbled upon the signatures and recognized them as something special.

Until she did, historians could only guess, based on the British reaction, at how popular the protest to the Townshend Acts became. In The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence, historian T.H. Breen wrote:

Although surviving records do not make it possible to know for certain how many people actually signed the rolls in Boston, British official feared for the worst. Their comments suggested that “Persons of all Ranks” did in fact take this occasion to voice contempt for recent British legislation.

Thankfully, we know now that the British were right. We recognize many of the 650 signatures, and they do indeed represent people “of all Ranks.” One of them is an exciting, if unsurprising, presence on a list like this, that of Paul Revere (whose signature is pictured above.)

Others are more unexpected. Several signatories whose names we recognize ended up remaining loyal to the British Crown when the Revolution broke out, Overholt notes. “At some point things got too radical and they said ‘I’m out,'” he guesses.

There were also several female signatures in an era when women weren’t known for their political participation. “I was especially excited to see that,” Overholt says.

So what’s next for the documents? Well for one, standards for maintaining archives have changed since 1942, Overholt notes, so they’ll likely “spruce up” the place where they shelve the documents. Beyond that, “we’re very glad to make this important discovery available to scholarly study,” Overholt writes. In other words, have at it, historians.