Chefology: The Parallel Lives of Chefs and Scientists

Welcome to Chefology, where married couple Ben Wolfe (a Harvard microbiologist) and Scott Jones (the chef de cuisine at No. 9 Park) explore the relationship between biology and haute cuisine. This is, quite literally, a marriage of science and cooking.

Photo by Ben Wolfe

When Scott left science to become a chef in the world of fine dining, many people asked how his training as a scientist could help him become a chef. While scientists aren’t whipping up souffles at the lab bench and chefs aren’t discovering cures for diseases, there are some surprising similarities in the approaches involved in being a chef and a scientist. As we’re both in the final phases of our career training—Ben as a post-doctoral researcher at Harvard and Scott as the chef de cuisine at No. 9 Park—and look toward the future of running our own lab and restaurant, we’ve reflected on some of the important similarities and differences in being a scientist and chef.

Method of Innovation

One of the most striking similarities between being a chef and a scientist is the method of creating an idea and obtaining results. In both science and cooking, you take known ingredients and use a common set of techniques to produce results. In cooking, it’s the synthesis of a meal or dining experience from a set of ingredients using known methods of cooking. In science, it’s the synthesis of an experiment using defined materials (lab rats, telescopes, chemicals in a test tube) with scientific equipment to obtain data about how something works. We both try to use what is known in our fields to create something new and interesting, a result that speaks to our creativity.

Career Paths

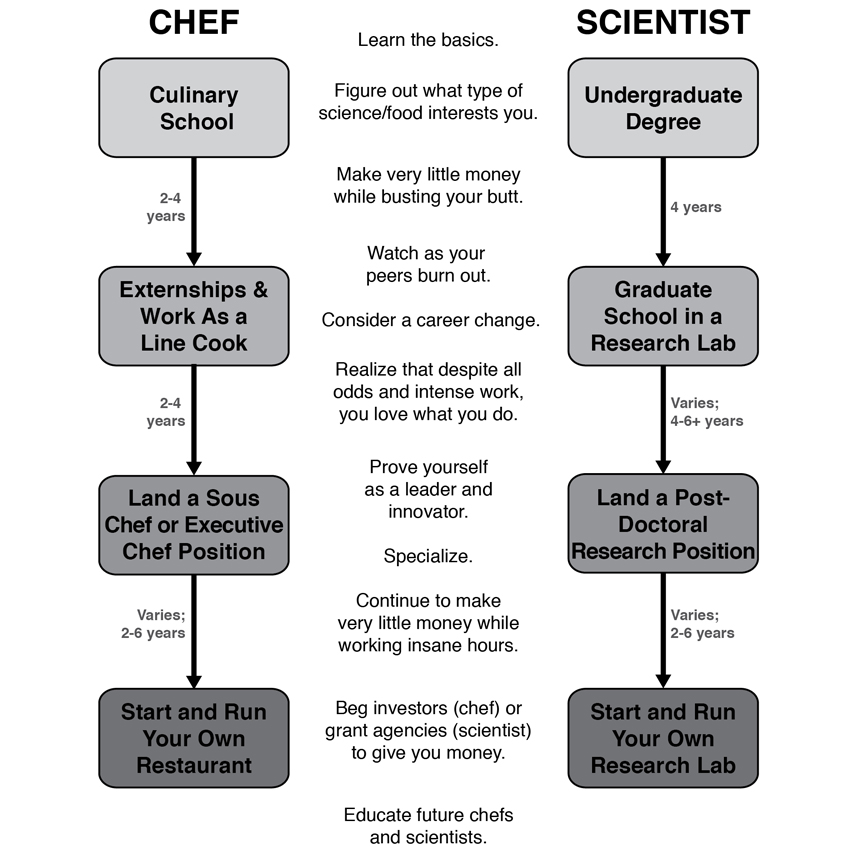

Another similarity between being a chef and scientist is the trajectory of the typical career. The steps from being a fresh high school graduate to becoming an independent chef or scientist with your own restaurant or research facility look something like this:

The time scales are similar. The mechanisms and opportunities for proving yourself are similar. And the intense pressure and low pay are also quite similar. The ultimate result is also the same—having your own restaurant/lab and having the freedom to do what you do best.

Audience and Impact

One of the main differences between chefs and scientists is the audience we reach. As a scientist, you often feel like you are working in isolation and have little impact on the everyday lives of the people around you. Few people will ever read your scientific papers that you publish in specialized journals. If you happen to do something sexy, maybe a newspaper will profile your scientific work. But in large part, most of the world doesn’t care about what you learn about in your test tubes at the lab.

As a chef, you have an impact every night the restaurant is open. Each week, hundreds of people eat your food. They taste something they’ve never tried before. Maybe they plan a trip to France inspired by the wine paired with the first course. Or get engaged after the main course.

One caveat to point out here is that some scientific discoveries from just one or two individuals can have a massive impact on the world. Most scientists chisel away at the massive realm of “the unknown” and slowly reveal how the world works one piece at a time. But the discoveries of penicillin, the structure of DNA, and radioactivity all came in large part from just a few individuals and had huge impacts on how we live our lives.

Rate of Success

Another huge difference between running a fine dining restaurant and running a scientific research program is the rate of success. As Scott develops tasting menus each week, his rate of success has to be high. The margins for loss are low and there is little flexibility to try something completely risky and unknown. Failure and negative results lead to loss of profit or angry Yelp reviews.

In science, failure is the norm. Most of what gets published in scientific journals are the positive results, when experiments worked out as planned and interesting data resulted. But most experiments fail or don’t provide the result you were expecting and never make it into a scientific paper. Negative results in science can be teachable moments and can provide useful ideas for future directions.

Time to Satisfaction

Another huge difference in our daily lives is the time to getting a satisfying result. For Scott, every night is an adrenaline rush, pumping out hundreds of plates of his food for people who leave stuffed and pleased. Each week he creates a new tasting menu (a set of experiments) that provides positive results for the diners.

The wheels of discovery in science move much more slowly. For Ben, that same level of satisfaction could take a month, a year, sometimes even several years. It’s easy to get lost in these long arcs of progress and is the reason so many graduate students leave science to pursue careers with more immediate satisfaction.

Ultimately, there are pros and cons to any career. When hours are long, and the pay is low, it is most important that you have faith in what you’re doing, and a belief and love for the core premise. For Scott, he left science because he lost faith in what he was doing, but found that love and faith in the kitchen. He might work 100 hours a week, standing on his feet all day, but he loves being in the kitchen, cooking and writing menus. Likewise, Ben has gone through periods with little success, and no clear path to the discovery he seeks. But ultimately he loves the process, enjoys the lab bench, and those rare moments of discovery are worth everything else.

And so, we both count ourselves lucky.