Bob Swartz: Losing Aaron

After his son was arrested for downloading files at MIT, Bob Swartz did everything in his power to save him. He couldn’t. Now he wants the institute to own up to its part in Aaron’s death.

Bob Swartz walks past MIT’s Building 16, where Aaron was caught downloading files from an academic archive in 2011. (Photograph by Mark Fleming)

There was a point, during the two years of legal proceedings that would overtake, and then shatter, both of their lives, when Bob Swartz and his son Aaron found themselves with a bit of free time. They had arrived at the Federal Reserve building, in Boston, to meet Aaron’s lawyer—one of dozens of meetings Bob would arrange in hopes of fending off the 13 felony counts against his son. But they were early, so they took a walk.

Aaron was Bob’s first child, the oldest of three boys, and he was a fragile, thoughtful kid from the very beginning. Growing up, Aaron and his brothers, Noah and Ben, had unfettered access to the nascent Internet, creating and coding projects of their own design. Evenings were spent building robots with Legos, playing Myst or Magic: The Gathering. Dinner-table conversations might concern the merits of a particular font, or Edward Tufte’s theories of information. “It was a house of ideas,” Bob says.

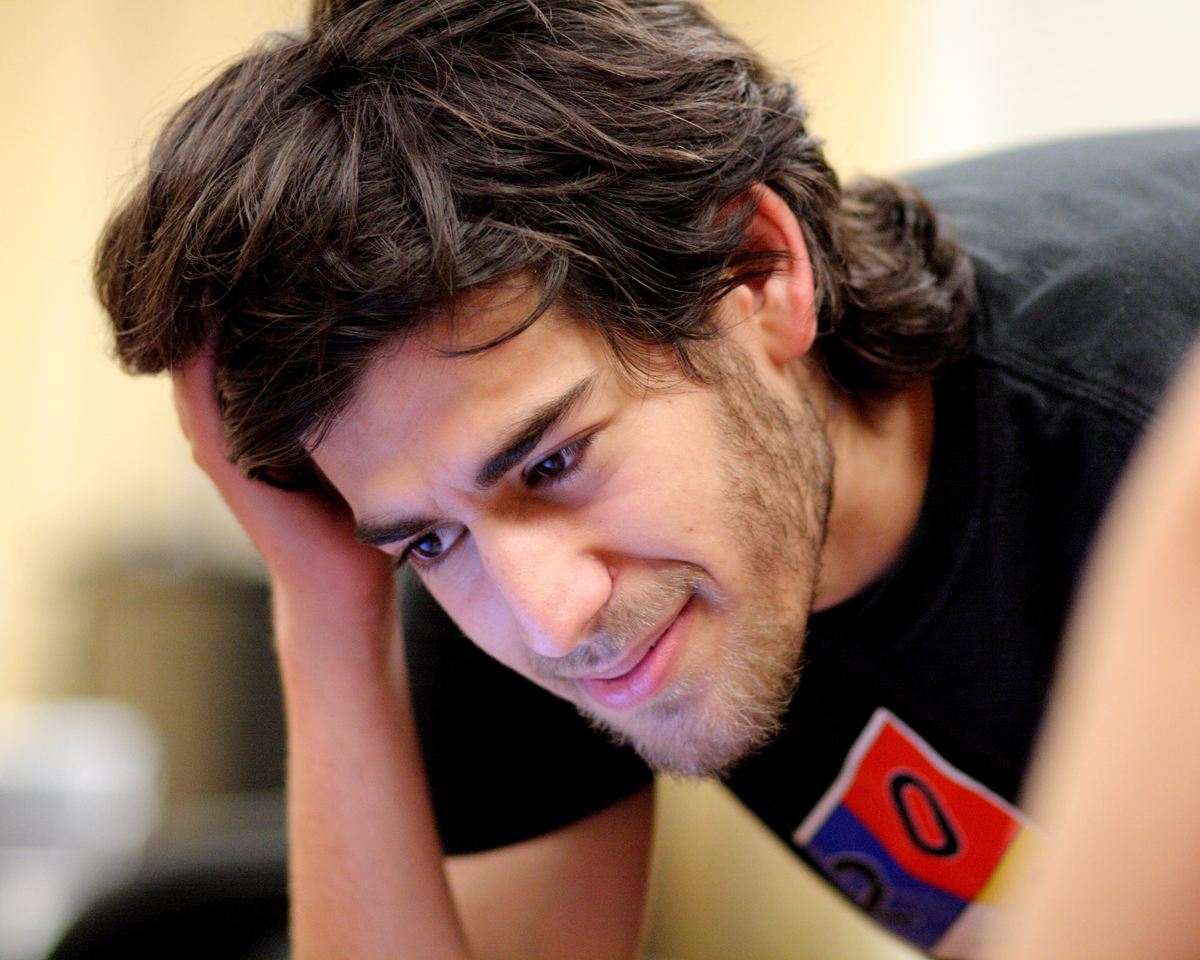

Aaron taught himself to read at age three, and became bored with school shortly thereafter. By ninth grade he became an anti-school activist, arguing that rote drills and homework assignments couldn’t teach kids how to think. Instead, he chose to be “unschooled,” documenting his progress on a blog he called Schoolyard Subversion. “He lived more of his life online than he did with his friends,” Bob says. “There was a degree of alienation that occurred, especially as he got older. He was working on the Internet and that was sort of terra incognita.” But Aaron found a network of friends online—many far older than he—who shared his interest in the future of the Web. Bob understood his dark-eyed, curious son’s enthusiasms. They spent time together in their Highland Park home, bonding over books as Aaron mowed through the family’s canon. One summer, they cataloged several thousand of their books according to the Library of Congress classification system. One night a fight erupted over standards. Aaron won.

Another time, Bob took Aaron to the Crerar Library at the University of Chicago, just as his own father had once taken him. Bob led Aaron through the stacks, pulled a book off the shelf, and cradled it in his hands. It was from the 1800s, a marvel. He told his son libraries were portals into the knowledge of the world.

Whenever Aaron needed advice, his father would share an insight from life or literature. “You always answer things in stories,” Aaron would say. That afternoon, as Bob and Aaron circled the block, they discussed the events of the past few months—Aaron’s arrest, when he was forced to the pavement; his strip search and solitary confinement upon arraignment; the increasingly circuitous route the U.S. Attorney’s Office was taking in negotiating the charges; their legal fees, which would soon clear $1 million; the looming felony conviction that Aaron feared. Aaron said he felt as though he’d been living in a version of The Trial, Kafka’s classic novel, which follows the incoherent prosecution of a defendant named Josef K.

Aaron had read the story in 2011, shortly after his arrest, and called it “deep and magnificent” on his blog. “I’d not really read much Kafka before and had grown up led to believe that it was a paranoid and hyperbolic work,” he wrote. Instead, he’d found it “precisely accurate—every single detail perfectly mirrored my own experience. This isn’t fiction, but documentary.”

Bob had admired Kafka, but didn’t remember the plot of The Trial. He asked Aaron to remind him how the story ended.

Aaron just stared at him.

“They killed K., Dad,” Aaron told him. “They killed him.”

Just a few months later, on January 11, 2013, nearly two years from the date when he was first arrested by a Secret Service agent in Central Square, Aaron Swartz hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment. He was 26 years old.

MIT may be the world’s most prestigious engineering school, with touchscreen maps installed in its building lobbies, but it remains a remarkably difficult place to navigate. To find room 485 in the Media Lab building, you pass through a series of silver double doors, then skirt a workshop where a garden of mechanical flowers gleam purple and silver under iridescent lights. There are no bumper stickers or flyers taped to the hall window of room 485; the blinds are closed. The only sign it’s occupied at all is the magnetic poetry on the door. Most of the tiles are a random scramble, but nine have been arranged to form the lines: Construct the future to be better for your children.

Bob Swartz is inside.

Bob has kind brown eyes and a brow crowned with gray fuzz. He wears a striped button-down shirt, khakis, a brown belt, a Tag Heuer watch with a simple brown leather strap, and sensible shoes. He swivels in his chair with one leg tucked underneath him. The room is small, only about 10 by 14 feet, but there are seven office chairs. “This is where the chairs hang out,” he jokes. There is weariness in his voice. “I feel bad putting them out in the hall.”

Bob lives in Highland Park, Illinois. For more than a decade, he has traveled to the MIT campus each month to consult on intellectual-property aspects of Media Lab creations. After Aaron’s arrest, these trips took on a new urgency: He had to file motions, meet with attorneys, plead with MIT administrators. Now, in the wake of his son’s death, coming here has become an exercise in grief.

“I see Aaron on every corner,” he says. “I pass by the building. I see MIT police. I remember, I remember him…” he sighs. “We spent a lot of time here. There are all sorts of painful aspects of what happened. They come back.”

In January 2011, just a few blocks from where Bob sits, Aaron was arrested for downloading 4 million copyrighted articles from JSTOR, an online archive of academic journals (JSTOR stands for Journal Storage). JSTOR charges libraries as much as $50,000 in yearly subscription fees to access its archive, but at the time, MIT’s open-network policy meant any visitor to campus could take advantage of MIT’s subscription privileges by using a guest login. Even so, Aaron was charged with excessive and unauthorized access to the university’s network under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

United States Attorney Carmen Ortiz, in the midst of a prosecutorial tear that would lead the Globe to name her 2011’s Bostonian of the Year, held up Aaron’s indictment as a warning to hackers everywhere: “Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data, or dollars,” she said at the time. “It is equally harmful to the victim whether you sell what you have stolen or give it away.”

In fact, Aaron faced stiffer maximum penalties than if he had used a crowbar: 35 years in prison and a fine of up to $1 million. “I said to him, ‘I’ll use every sinew in my body and every synapse in my brain to get you out of this mess,’” Bob says.

Bob pleaded with MIT’s administrators and lawyers to intervene. Joi Ito, the Media Lab’s director, also petitioned the university to consider it a “family matter” and speak up regarding the charges of Aaron having “unauthorized access” on a campus where anyone, anywhere, could log into the JSTOR system—or any library database—with a simple Ethernet connection. But instead, MIT took a position of “neutrality.” It made no public statements for or against Aaron’s prosecution or about whether he should be imprisoned. This is the other reason why Bob’s visits to MIT are so painful: He can’t walk through campus without feeling that MIT betrayed his son.

“I always felt that MIT would act in a reasonable and compassionate way and that MIT wasn’t the issue,” Bob says. “I didn’t understand the depths of what MIT had done at that point.”

Bob has developed a routine during his Cambridge visits. He rooms at the Kendall Hotel. In the evenings, he’ll stroll to Emma’s for a pizza, or visit the Coop bookshop in Harvard Square. Some days he eats at Legal Sea Foods, where he often overhears drug developers debating the risk of funding new research. This bothers him. He believes people should be willing to take risks, to try and to fail, and that through failure comes change and invention.

“It all came from my father,” Bob says.

Bob’s father, William Swartz, was a successful Chicago businessman who parlayed his wealth into social activism. He founded the Albert Einstein Peace Prize Foundation, and was active with Pugwash, the nuclear disarmament group that won the Nobel Prize when Aaron was eight. Through Pugwash, William befriended Jerome “Jerry” Wiesner, the 13th president of MIT and a cofounder of the Media Lab. When Bob was a teenager, his father would send him to pick up Wiesner at the airport when he came to town. “Jerry had an incredible heart about things and was just an extraordinary human being,” Bob says. In his memories, Wiesner embodied all that MIT stood for: compassion and creativity, challenging authority, and pure scientific inquiry.

Bob was never accepted to MIT—his dyslexia led to mediocre grades in high school—but he convinced the university to let him complete some undergrad and graduate work there as a special student in the math department. He arrived just as MIT was beginning to embrace, and celebrate, its hacker ethos. At MIT, a hack can mean benignly breaking into a computer system, but it can also mean breaking into the university’s underground network of tunnels, inflating MIT balloons during the Harvard-Yale game, or measuring bridges in Smoots.

“Hacking was investigating a subject for its own sake and not for academic advancement, exploring inaccessible places on campus, doing something clandestine or out of the ordinary, or performing pranks,” wrote Brian Leibowitz, editor of The Journal of the Institute for Hacks, TomFoolery, and Pranks at MIT. What started as a series of stunts evolved into elegant acts of cunning that have come to define the institution’s values. “Hackers believe that essential lessons can be learned about the systems—about the world—from taking things apart, seeing how they work, and using this knowledge to create new and even more interesting things,” Steven Levy writes in Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. “They resent any person, physical barrier, or law that tries to keep them from doing this.”

Bob’s eyes brighten when he’s asked about his own history of hacks. He says nothing, but just offers a sly grin; it’s the same smile he passed along to his son.

In time, Bob took over his father’s business and adapted it into a software company. He married and raised three boys of his own, who picked up his penchant for computing. “Before the World Wide Web existed, we were using the Internet,” Bob says. “We all understood very early on that the Internet was going to change everything.”

Aaron began to teach himself simple computer programs while still in elementary school. When he was 12, he accompanied Bob to MIT and sat in on Philip Greenspun’s Web-development class. “I was so excited by the class that I immediately went home and tried to make something,” Aaron wrote to a friend years later.

Even then, Aaron saw the Web as a platform for freely sharing. A year before Wikipedia launched, he built an open-source encyclopedia, which he submitted to Greenspun’s ArsDigita contest for teen programmers. As a finalist, he met the inventor of the Web, MIT professor Tim Berners-Lee. He followed that up by coauthoring some of the first codes for RSS feeds, at age 14; working on the frameworks for Creative Commons with famed Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig, at 15; and helping to build the website Reddit, the sale of which made him a millionaire a week before his 20th birthday.

Like his father, Aaron was never an MIT student—he had done a brief stint at Stanford, but found it intellectually lacking. Instead, he worked with Lessig as a Safra fellow in Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, and began to focus on the political potential of his coding skills. He cofounded Demand Progress, an activist group that railed against Internet censorship. He juggled projects on open access, rethinking copyright restrictions, and ending corporate corruption, and had coauthored a Guerilla Open Access Manifesto, which argued that public access to scholarly journals was a moral imperative. Aaron approached every stage in his life with an unbridled idealism. Whenever he grew frustrated or disappointed, Bob always encouraged him to learn from failure. Aaron’s goal, he says, was simply to “make the world better.”

Aaron lived in Central Square, moving fluidly between Harvard and MIT’s campus. At MIT, he visited friends and family, including his brothers, who interned at the Media Lab. Aaron’s girlfriend at the time, Quinn Norton, described his familiarity with MIT: Aaron “had a history of hacking,” she said in an interview with MIT after his death. Sometimes when she’d call him he’d tell her, “Can’t talk now, in the middle of breaking into a building at MIT with a bunch of students.”

“It was a fun place where he could do that,” she said. “And I think he did it at MIT because it was in the spirit of the things that he did, and other people he knew did, at MIT.”

Norton told MIT that Aaron was in the habit of gathering big data sets, and that she’d helped him scrape millions of books in the public domain from Google Books: “It was a game. He was a data pack rat…He really loved mashing them with scripts and going through and analyzing them and trying to pull stuff out of them.… I think that he somewhat reasonably thought that if MIT didn’t like it they’d just tell him to stop.”