Will the Internet Find Maura Murray?

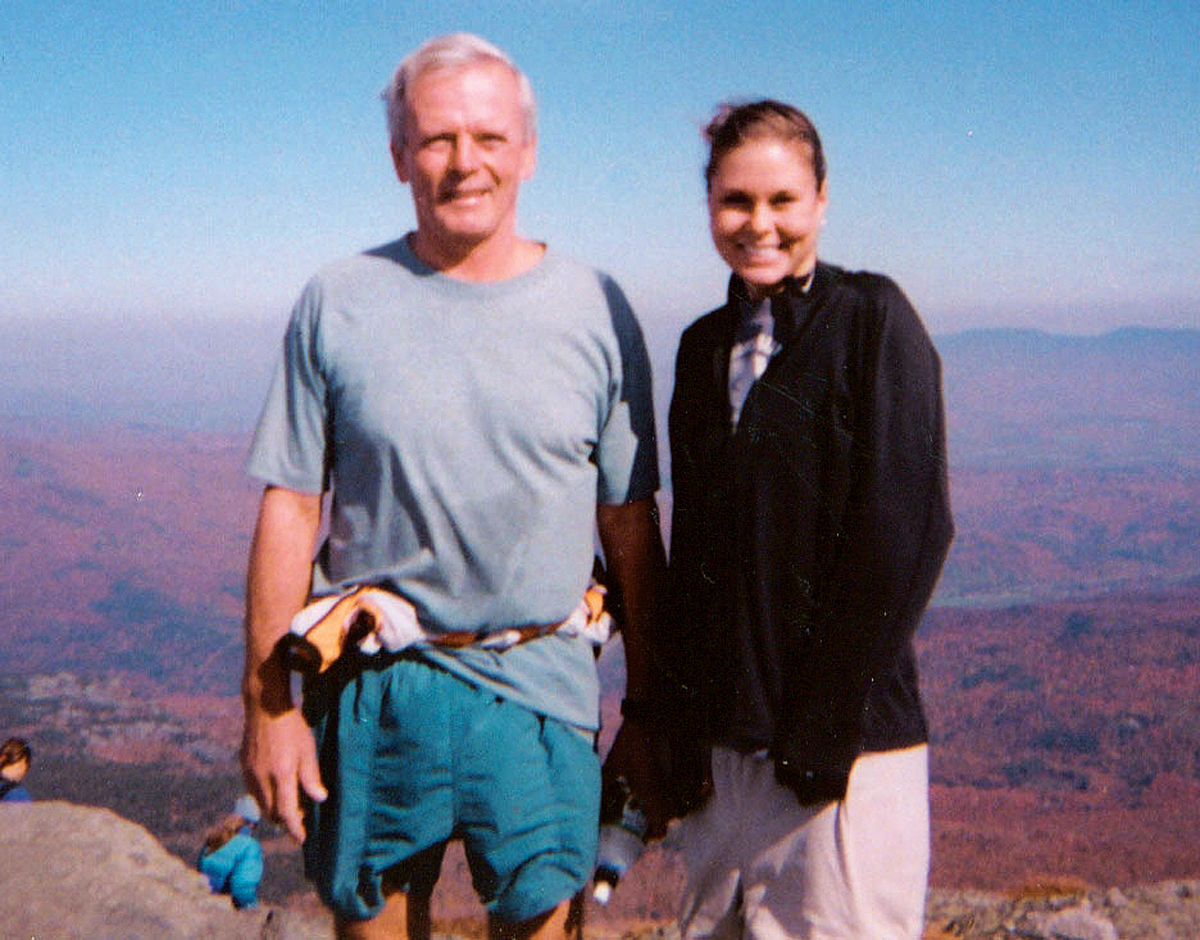

Fred Murray and his daughter, Maura, before she disappeared.

Over the next couple of days, as she and her father tried to figure out the car’s insurance situation, Maura started to make travel plans: Just before 1 p.m. on Monday, she called the owner of a condo rental in Bartlett, New Hampshire; she also dialed 1-800-GOSTOWE, but did not make a reservation at one of the hotels in the area. The same day, she sent an email to her boyfriend:

“I love you more stud. I got your messages, but honestly, i didn’t feel like talking to much of anyone, i promise to call today though. love you,Maura”

Hours later she left him a voice mail, promising to talk. And she sent emails to her professors and supervisors, informing them—falsely—of a death in her family.

When she left her dorm room, did she hint at what lay ahead? Some reports claim she had packed her belongings and taken art off her walls—evidence, perhaps, that she was leaving for good. Her father says the floors had been cleaned over Christmas break, which explains why some of her things were still in boxes. But almost everyone agrees that Maura was planning to leave campus for at least a few nights. She withdrew $280 from an ATM—almost all of the money in her account—and purchased, according to police, Baileys, Kahlúa, vodka, and box wine from a nearby liquor store. She checked her voice mail at 4:37 p.m., her last known call. She told no one where she was going.

On the Internet, Maura’s disappearance is the perfect obsession, a puzzle of clues that offers a tantalizing illusion—if the right armchair detective connects the right dots, maybe the unsolvable can be solved. And so every day, the case attracts new recruits, analyzing and dissecting and reconstructing the details of her story with a Warren Commission–like fervor. The late-night car accident after the party. The father visiting with $4,000 cash in his pocket. The crying episode. The box of wine. The MapQuest printout. The rag in the tailpipe.

Online sleuthing stepped into the spotlight this past April, when the FBI asked for the public’s help in identifying the Boston Marathon bombers. The agency, though, was drawing on a long tradition of crowdsourcing investigations—one that stretches from Wild West wanted posters to TV’s America’s Most Wanted. But it was also tapping into the more recent tradition of independent, online, open-sourced sleuthing: citizen detectives, often strangers living miles or continents apart, sharing information and working in unison. The practice can lead to stunning revelations, as when crime-blogger Alexandria Goddard uncovered details of a high school rape case in Steubenville, Ohio, by screen-grabbing the tweets of partygoers. And, famously, it can lead to false accusations: Some Reddit users helped identify the brand of hats worn by one of the marathon bombers, but others famously implicated numerous innocent standers-by.

Now, at least online, it often seems as there’s no such thing as a cold case. But when Maura Murray disappeared, the social Web was in its infancy. There was no YouTube and no Twitter. On the day Maura went missing, Facebook was five days old. And so you can read the history of her case as a parable about the evolution of online sleuthing. In the months after Maura vanished, one of Rausch’s friends launched a site in an attempt to publicize the case. Long-gone sites like alt.true-crime and crimenews2000.com began reposting newspaper articles, as well as the standard details. In November 2004, nine months after she vanished, a second cousin of Maura’s started the website mauramurray.com. A Maura Murray string was even created on justiceforchandra.com, a site set up to discuss the case of Washington, DC, intern Chandra Levy, who had gone missing three years earlier.

In February 2005, members of the DIY detective message board websleuths.com jumped into the fray. Anonymous posters with names like Grassyknoll2 and CyberLaw attempted to piece together a time line, wondering why Maura would have partied on Saturday night, or what made her so upset at work. In 2007, pages on Facebook and MySpace were created in hopes of gathering tips. And in the Franconia city forum on the small-town message board topix.com, more than 42,000 comments have been posted on a Murray thread in just the past four years.

Just as with anywhere else on the Internet, the discussion can run from constructive to abusive. Debates range from the backgrounds of the neighbors along Route 112 to whether Maura was trying to use the rag in the tailpipe to burn her car. The forums are awash with theories: Some believe she was taken by a serial killer monitoring the police scanner. Others think she faked the accident and bolted for Canada. The most obsessive even make pilgrimages to the curve on Route 112—snapping photos, taking measurements, attempting to reconstruct the accident.

Within the past year, a few users have broken off from the free-for-alls of the message boards and launched stand-alone sites with a sole focus on finding Maura. One of them, called Not Without Peril, was created by Joseph Anderson, 30, an attorney from Whitman, Massachusetts, who came across Maura’s case in early 2013 while researching another missing person. He became fascinated, and began commenting on sites under the pseudonym “Sam Ledyard.” In the summer of 2013 he launched his own site with a few other regular commenters, naming it after the title of the book that was found in Maura’s car. In just a few months, it has racked up more than 22,000 comments, Anderson says. The contributors to the site have come to know one another, and have taken on roles—for instance, one is known for his connections on other Maura Murray sites; another is a real estate agent, adept at pulling useful info from the MLS database. Anderson spends hours per day on Maura’s case. When he gets home from work, he usually hops on the computer and starts digging. “It could go on from 7 till midnight,” he says.