Five Takeaways from the MBTA’s First Annual Report

Red Line photo via Wikimedia Commons

The MBTA’s Fiscal and Management Control Board released its first annual report on the state of the troubled transit agency and the findings aren’t great. Here are five takeaways that are nothing less than depressing:

1. The MBTA’s state of good repair backlog is more expensive than we thought

The most recent reviews of the MBTA’s maintenance deficit resulted in a $7.3 billion price tag spread across 25 years. When a typical inflation rate of three percent is taken into account, however, the price balloons to $24.8 billion. The FMCB, still basking in its new car smell, is not looking to the legislature for financial assistance to deal with this staggering price tag, and insists the agency will be able to tackle it on its own. “The Board believes it must first demonstrate that it can make the best choices for allocating available capital and deploy that capital investment with accountability and results,” according to the report.

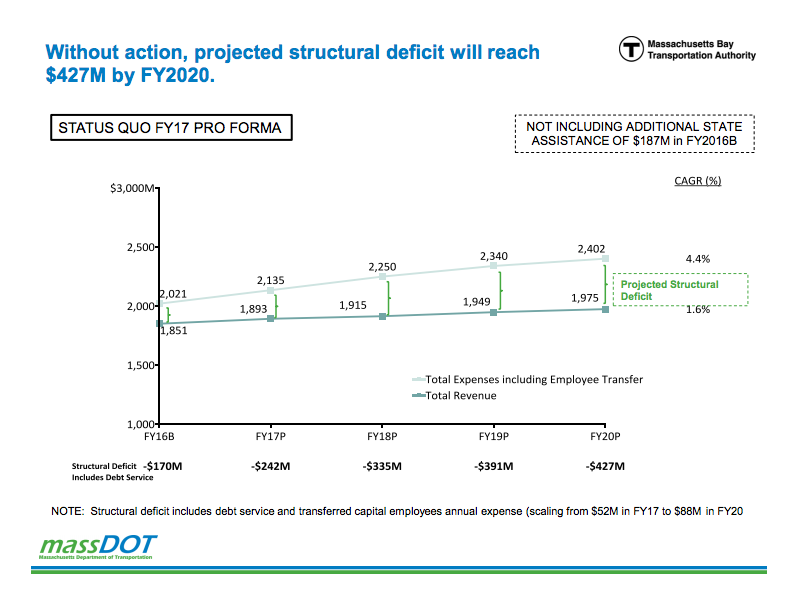

2. The MBTA’s structural deficit is spiraling out of control

While the MBTA’s level of ridership has remained relatively flat since the turn of the millennium, operating expenses at the MBTA increased at an annual average of five percent. This means revenues have not kept pace with the cost of operating the MBTA. If action is not taken soon, this problem will become even worse, the report warns. On top of the increase in annual operating expenses is a 17 percent uptick in the MBTA’s debt service costs spread over four years. “Failure by the FMCB to decisively control and eventually balance the MBTA’s structural operating budget will jeopardize even further the Authority’s ability to make badly needed investments in maintenance State of Good Repair and other critical areas of capital spending,” per the report.

MBTA

If the MBTA takes action to eliminate its annual structural deficit in the next fiscal year, the agency could see savings of upwards of $1.2 billion through 2020. That’s money that could go towards addressing the system’s maintenance backlog. Plus, these savings would mean the $187 million it receives from the legislature would not go toward fixing budget gaps, but fixing tracks and trains.

To obtain a balanced budget, the FMCB wants the MBTA to first contain its own costs, then increase system revenues. After those two options are exhausted, only then should they consider fare increases and changes to service frequency. How does the MBTA contain its own costs? Conduct a line-item review of its entire budget from-to-bottom, something the MBTA “has rarely if ever conducted.” So far, the agency has identified $50-60 million in potential cuts that are non-essential to the operation of the MBTA.

On the revenue side, the MBTA is looking to more aggressively monetize its existing sources of income, such as parking, real estate, and advertising. Fares are another matter, and riders could be seeing a possible 10 percent increase in fares sometime in the next year or two.

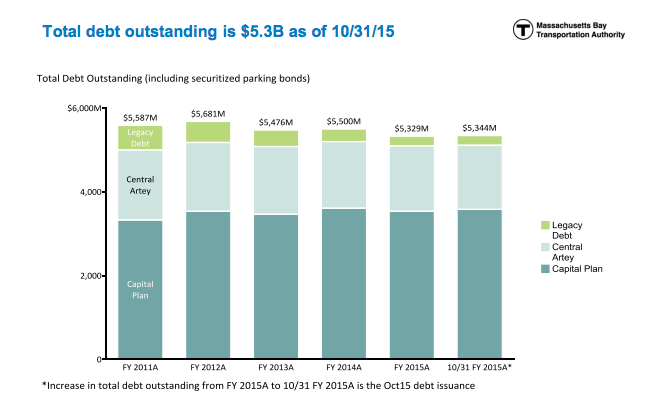

3. Debt is an albatross around the MBTA’s neck

Debt service is crushing the MBTA, accounting for roughly 30 percent of its total annual operating expenses. The majority is from the agency’s capital plan, not the Big Dig, as is popularly believed. As of October, the MBTA has $5.3 billion in debt. “In the past, the MBTA’s mistake has been to take on more and more debt without setting a clear path to repay it; the FMCB will not allow that bad practice to continue,” according to the report.

MBTA

Debt is not all bad for the MBTA, as it is how the agency pays for crucial capital projects, but some form of state assistance with the agency’s Big Dig and legacy debt is needed.

4. The MBTA’s budgeting process is problematic

For whatever reason, the MBTA has over 532 employees involved in procurement and asset improvement on its capital budget instead of its operating budget, meaning their salaries are paid for through bonds or grants. This is problematic, because it goes against common accounting practices and it’s using funds that could (and should) be bookmarked for other purposes. Beginning in 2017, the FMCB will transition the remaining employees on the capital budget to the operating budget. The move is expected to add between $52-88 million to the agency’s operating budget.

5. The Green Line Extension, while messy, has proved instructive

The Green Line Extension headache has been a proving ground for the management problems facing the MBTA. When the FMCB reviewed how the budget for the GLX ballooned by a billion dollars, they found that the agency rushed to complete the project and lacked the necessary inhouse knowledge to oversee it properly. Even though the future of the GLX is in doubt, the MBTA’s focus going forward is clearly on returning the entire system to a state of good repair. Still, there is a real need to reform the agency’s management, planning, and procurement procedures.

The MBTA’s procurement and budgeting of expansion projects has contributed to the erosion of public confidence in the agency. “The ongoing pattern of early low estimates that balloon later in the process serves to distort the planning process, damages the MBTA’s credibility with the public, and reduces needed spending on maintenance,” according to the report.