Les Otten’s Last Resort

A view of the Balsams from the adjacent lake. / Photograph by Greta Rybus

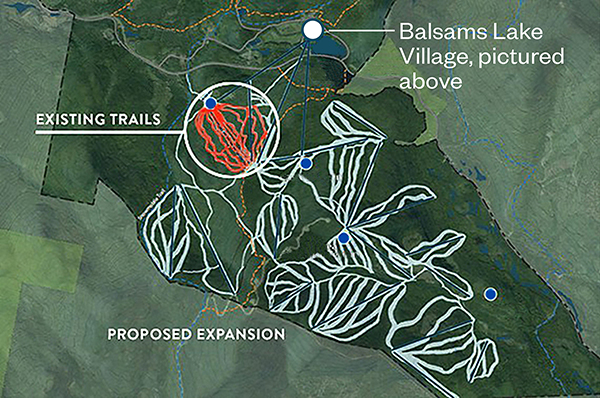

A map of the area shows the enormous scale of Otten’s undertaking. / Courtesy Rendering

The marketing ploys and expansion worked. By 2000, Sunday River spanned eight peaks and drew half a million skiers a year. The kicker was that all of that growth had occurred while the ski industry as a whole was virtually flat. “It’s the most incredible growth story in at least four decades,” says Tim Cohee, who worked for Otten in the early 1990s and now runs the China Peak ski resort in California. The business press agreed. In 1989, Inc. magazine named Otten its turnaround entrepreneur of the year.

Otten was busy with other ventures, too. He’d cofounded a charity to help people with disabilities ski, as well as a construction company, among other endeavors and investments. It seemed that every venture he touched flourished, so his dreams kept getting bigger. In the 1990s, Otten bought up several other ski resorts in New England, including Killington, and combined them into a conglomerate dubbed American Skiing Company. Over time, Otten looked west, envisioning a bicoastal ski empire. He developed Canyons, in Utah, and eyed Steamboat, in Colorado. Then, Otten says, the problems began. “A bunch of Wall Street guys rented a private plane and came up to see me,” he tells me. “Goldman Sachs, DLJ, Furman Selz, Merrill Lynch.” Their goal? Convince Otten to take his business public. “It was my decision,” Otten says. “But when these guys are sitting there telling you what they think will work, you believe ’em.”

At the time, Otten was all ears. Since he owned virtually all of American Skiing Company’s equity, no one stood to make more from the deal than him. The day the company went public, in 1997, selling shares at $18 a pop, Otten’s stake was worth almost $300 million. But it wouldn’t last. “It was too much, too fast, too big,” he says. A pair of bad winters, frenetic construction at many of Otten’s resorts, and a downturn in the real estate market—all while the company continued to acquire new properties—left American Skiing’s finances in tatters. The stock price plummeted. Desperate for cash, Otten cut a deal with a private equity firm. Oak Hill Capital Partners saved American Skiing from potential bankruptcy with a $150 million injection, but the side effects were devastating.

Following the deal, Oak Hill gained control of the board—and the company. Within two years, it decided to sell off American Skiing’s resorts one by one. The stock price crashed again when Oak Hill broke the company up, wiping out shareholders. Otten himself lost virtually his entire stake—about 50 percent—in a company that had once been worth close to $600 million. “It was unpleasant,” he says. “But it didn’t sour me.” Even as American Skiing, his life’s work, was coming undone, Otten had already started chasing his next big dream.

Around Christmas of 2000, television producer Tom Werner, who had made a fortune with such hits as Roseanne and The Cosby Show, took his then-girlfriend, Katie Couric, to visit Otten at Sunday River. At the time, American Skiing’s stock was tanking and Oak Hill had taken control of the company. Within a few months, Otten would resign.

Still, Otten’s spirits seemed higher than ever as he joyously played the role of backwoods magnate. He put up Werner and Couric in one of his hotels and invited them to his lake house to chat near the fire under a vaulted wood-beam ceiling. Otten had big news: For his next act, he wanted to buy the Red Sox.

Throughout his career, Otten had rarely jump-started his ventures with more than a few million of his own. Other than when American Skiing’s stock was at its peak, he’s never really had enough cash to pull it off. Instead, he seeks out those with deeper pockets and charms them into backing him. “There aren’t many people on the planet that are more talented at convincing people that he’s right and that he can get the job done,” says Brian Fairbank, a ski industry veteran who co-owns Jiminy Peak and Cranmore. “He’s a master, and that’s a big talent.”

Which perhaps explains why Werner didn’t laugh Otten out of the room when he announced his latest big idea. Instead, Werner replied, “Did you know I used to own the San Diego Padres?” And with that, Werner had the distinction of becoming Otten’s first investor.

By all accounts, Otten’s desire to buy the Red Sox centered on a single idea: save Fenway Park. During the late 1990s, many city officials believed Fenway was too old and decrepit to keep. Bidders vying to buy the team were expected to present plans—and a location—for a new ballpark. Fenway would be torn down, which Otten viewed as a disgrace.

It’s hard to look at Otten’s current woodsy lifestyle and his desire to preserve Fenway and the Balsams without sensing a yearning for the past. “Through my father’s eyes,” he told me one day, “I saw the entire Industrial Revolution.” It seems fitting that his second love, after skiing, is baseball, the sport of nostalgists. Otten also wanted to keep Fenway for economic reasons. There was too much brand equity tied up in the ballpark to consign it to demolition, he says. “We projected that the value of a seat in Fenway Park was going to be significantly greater than in some new cookie-cutter ballpark.”

In November 2001, John Henry joined Otten’s team, bringing mountains of cash and additional baseball ownership experience. Suddenly, the group was a serious contender. The very next month, the Otten-Werner-Henry group was chosen as the winner of the auction. Their bid of $660 million was double the previous highest price paid for a baseball team.

The addition of Henry to the group brought another consequence: Otten’s demotion. Originally, Otten had envisioned a prominent role for himself in the Red Sox organization. But Henry, an aggressive billionaire commodities trader, wanted to be the top dog and had the money to assert himself. And after all, Henry’s contribution was by far the largest. Otten wound up in a somewhat marginal consultant’s role, with a relatively small ownership stake in the team. He contributed marketing ideas and collected two World Series rings. In the end, though, his lasting contribution would always be his first: helping to save the team’s park. In 2007, he sold his shares back to his partners—at a significant profit—and moved on.

Otten’s Red Sox foray had certain parallels to his American Skiing Company project: It worked because he paired an audacious plan with a keen sense for what consumers wanted, but, ultimately, he lost control. “That’s okay,” he says now. “I saved Fenway Park. My kids know it. Everybody inside baseball knows it, and the most important thing is Fenway is still there. And it could be for another hundred years.”

To reach the Balsams, drive I-93 north from Boston—past Manchester, through the White Mountains, and between the cliffs of Franconia Notch—until cell service becomes spotty and the granite landscape jagged. Turn onto the backwoods roads and continue toward the Canadian border. For the rest of the trip, you won’t see a building higher than three stories, a town of more than 5,000 people, or, for that matter, a stoplight.

When I made the drive last September, lumber trucks rumbled down roads lined with political signs, including blue Donald Trump banners, a “Hillary for Prison” poster, and a handpainted billboard—“Northern Pass Kiss My Ass”—decrying a local infrastructure project. This is the North Country, a nearly forgotten region devastated in recent years by one economic blow after another. First the paper mills closed, then the Ethan Allen factory, and, finally, the Balsams. Thousands lost their jobs. Since then, opioid addiction has surged and the area has experienced a mass exodus of the unemployed. Carol Sandhammer-Pires, owner of the Moose Muck Coffee House, in Colebrook—population: 2,301—likens the post-2008 economic recovery to a slow-moving wave. “Way up here,” she says, “it takes even longer for it to reach you.”