A Crash Course in Crisis Economics*

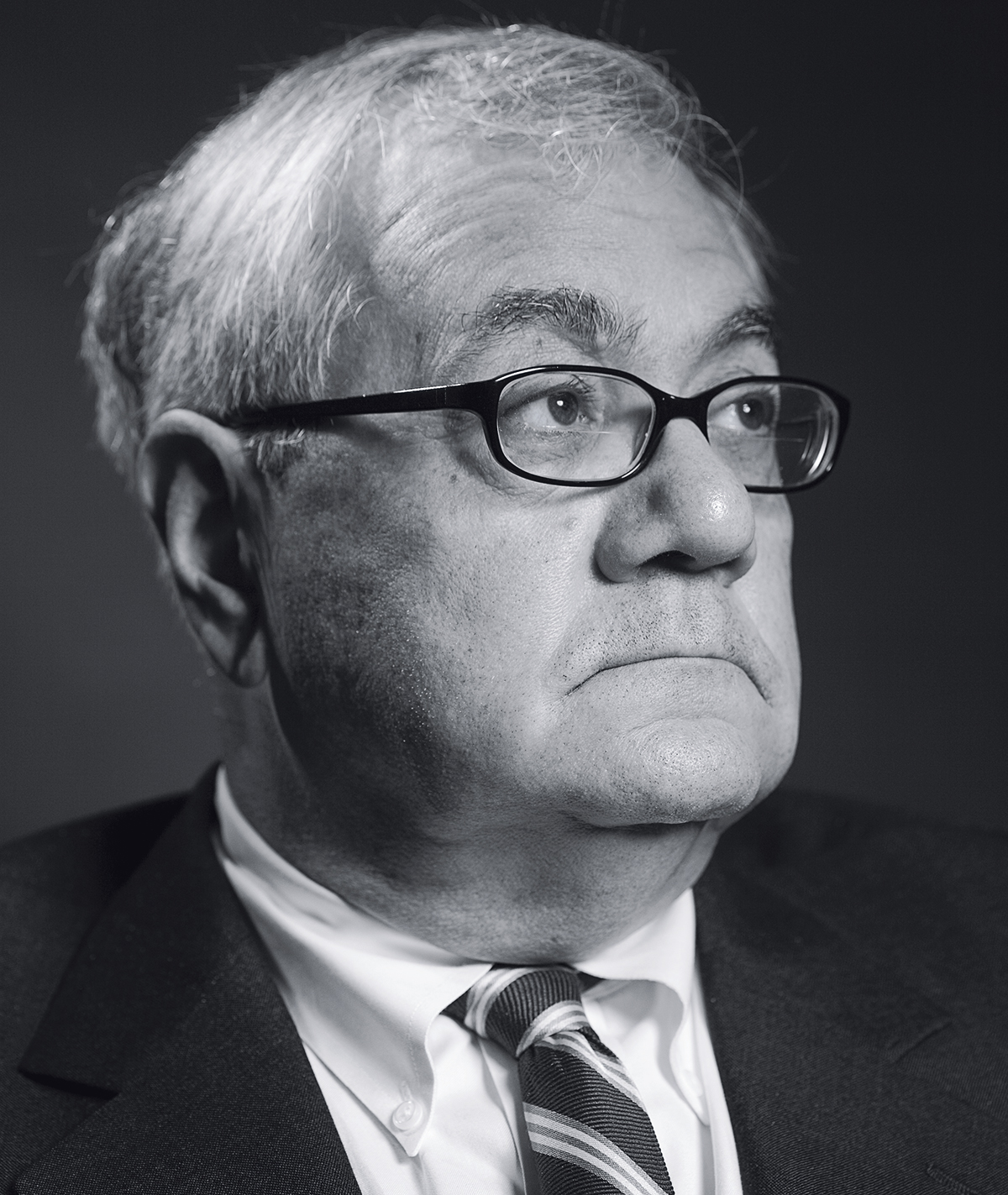

Photograph by Sadie Dayton

I. A Refresher on Recent Events and a Primer on Important Terminology

Inside Barney Frank’s district office in Newtonville, a strikingly well-dressed man who happens to be in the business of manufacturing solar panels is patiently waiting to speak to someone on the congressman’s staff. This summer the man’s Marlborough-based company had been working on raising $375 million by selling convertible debt — bonds affixed to stock options — to the public. As a condition of securing the financing, the investment bank handling the offering required the company to lend it some 31 million of its shares. But the deal never went through, because the investment bank was the soon-to-implode Lehman Brothers…a consequence of which was that the well-dressed man’s company, Evergreen Solar, never got its shares back. Barclays, the British bank that bought Lehman’s investment banking division, isn’t letting the shares go, forcing Evergreen Solar into suing to get them back. And so the well-dressed man is here, to learn what other options he might have.

Such are the Kafkaesque scenes that emerge during the complete breakdown of a system, which, you may have noticed, is what we now find ourselves living through. It’s not a situation made for easy comprehension, but when economists and politicos and anyone else with a time-share on the moment try to explain it to us, two big themes tend to come up: “information asymmetry” and “moral hazard.” You cannot have a halfway-serious discussion about the economic crash — or, for that matter, American politics generally — without them, and so it is with them that we will begin.

In a market context, information asymmetry is what it sounds like: a gap in understanding between two sides of a transaction. Despite his reputation as a partisan, Barney Frank views political problems through that same lens, framing most as a series of misunderstandings, miscalculations, and misplaced misgivings. He is equally deeply versed in moral hazard, which refers to the tendency of people who’ve been insulated from risk to behave differently (i.e., more riskily). The term was coined in the 19th century by life-insurance underwriters concerned that their customers would be increasingly likely to indulge in unhealthy excess; more recently, it has come to also be used in reference to prolonged stays in the corridors of Washington. Promoted by conservative Republicans, the idea began to take hold roughly 30 years ago — right around the time Frank won election to Congress — that the federal government is a veritable landfill of morally hazardous waste, manned by machine pols unnaturally insulated from the threat of losing their jobs and wanting only to spread the wealth of a risk-free government-payroll life to friends and lazy poor people.

But times change, and with them, the hazards. As when the financial system caved in on itself this September, the casualty of a decade-long ritual risk-burning started by hedge funds and sustained by a long list of all-too-eager accomplices. Within a few weeks, Henry Waxman, the California Democrat and chair of the House Oversight Committee, had hauled in some of the country’s leading plutocrats: Lehman CEO Richard Fuld and a pair of former CEOs of AIG — the insurance giant that had booked billions in profits on policies it couldn’t honor, then went golfing at the St. Regis after the government promised to bail the company out — and finally Alan Greenspan, whose false ideology was the system’s original sin. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, for her part, gave a speech laying blame squarely on the “recklessness” and “irresponsibility” of “anything-goes” Republican policies. A member of her caucus reportedly wrote an e-mail vowing not to vote for a “$700-billion-dollar giveaway to the most unsympathetic human beings on the planet” unless it was “as punitive as possible” and included curbs on executive behavior “that would serve no useful purpose except to insult the industry.” It was astonishing: For once, the Moral Hazard Majority belonged to the Democrats.

Curiously, Frank wasn’t joining it. Hill insiders found it noteworthy that he’d ceded so much turf to Waxman when he could have done his own excoriating of corrupt billionaires in front of the Financial Services Committee, which he has chaired for the past two years. Instead, as Frank’s staff in Washington worked the phones monitoring the minutiae of the bailout package, he returned to his district and ran a campaign for reelection that resembled a lecture circuit as much as anything else. He visited the editorial boards of local newspapers and spoke at chamber of commerce breakfasts, community luncheons, and Democratic Party dinners. In between, he went on what seemed like at least one national news show a day to discuss the Wall Street mess.

“People should not be surprised that people who do not believe in government are incompetent at running it. It’s like making me chief judge of the Miss America contest,” Frank said at one of his stops, a fundraiser in New Hampshire, cracking up the audience. It was superficially a partisan speech to a thoroughly partisan crowd. But though those who seek to blame the crisis on him would never believe it, it was also given in pursuit of a higher purpose. “Barney Frank is not a hypocrite,” says Larry Lindsey, the former George W. Bush chief economic adviser (who over the summer wrote a column for the conservative Weekly Standard praising Frank’s “intellectually honest” mortgage foreclosure legislation). “He’s been dealing with this crisis in a very positive way. He understands there’s nothing criminal about being wrong.” The real hazard, Frank understands all too well, is in failing to try to open the other side’s eyes. A month after securing his 15th term, he continues to give his speeches.