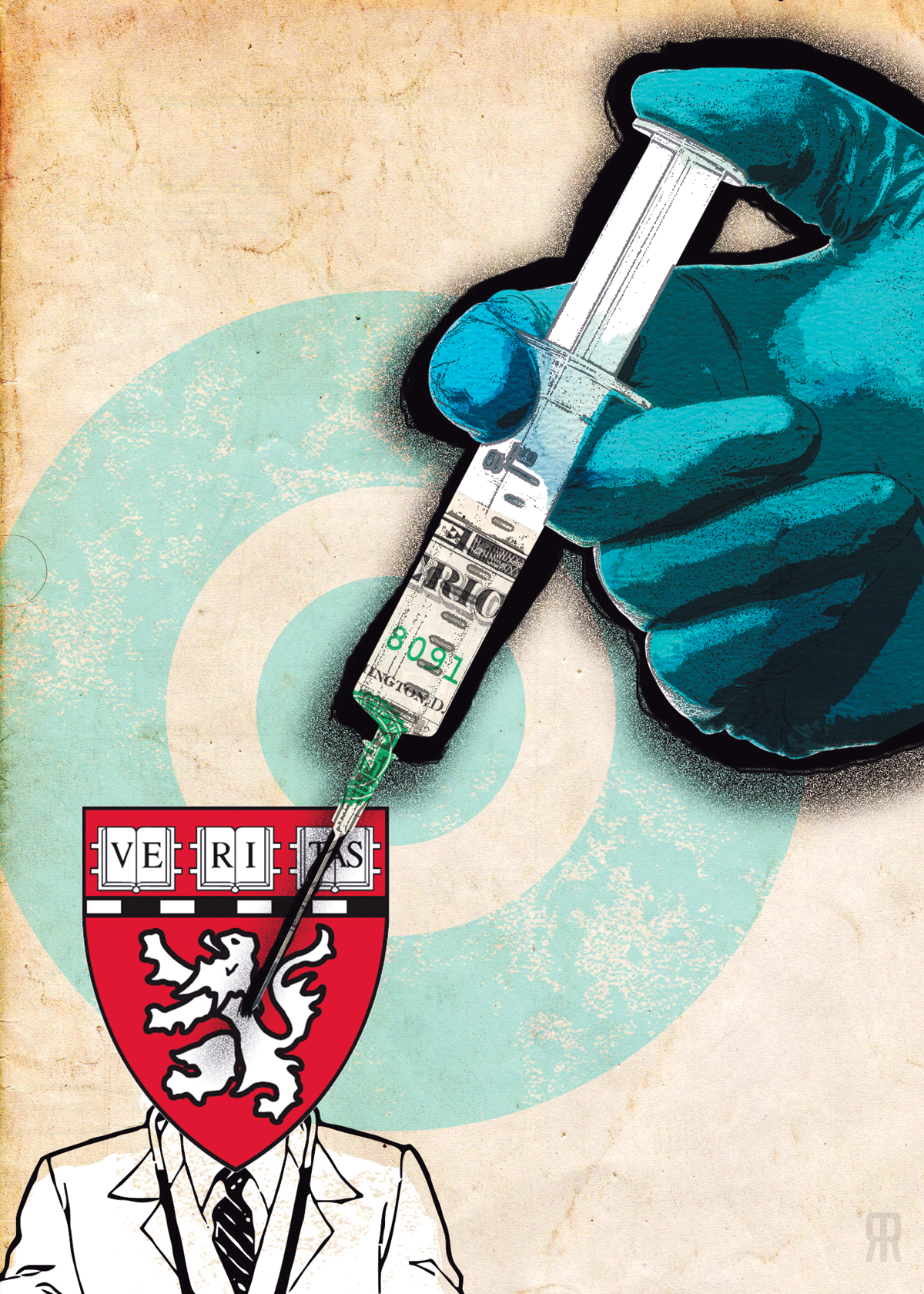

Bitter Pills

Illustration by Rafael Ricoy

It was like something out of Michael Clayton, only with Big Pharma as the villain: A Pfizer drug rep, clad in a black suit, was taking cell-phone pictures of students protesting Harvard Medical School’s ties to the drug industry. Staged last October, the gathering was sparsely attended, with a few students holding signs and a petition delivered to an empty office (the dean was out of town). But the photographer’s appearance was notable enough to merit a story in the New York Times, which eventually led to an investigation by U.S. Senator Charles Grassley.

And so it goes for Harvard Medical School, which has been under intense scrutiny since 2008, when a series of incidents put a spotlight on its symbiotic, if awkward, relationship with drug companies. The trouble started that summer, after Joseph Biederman, a Massachusetts General Hospital child psychiatrist and HMS professor, was found to have taken more than $1.6 million in payments (which he failed to fully disclose to the school) from the maker of a major antipsychotic he’d been prescribing. There were other stories, too, like the student who had sat in class listening to a professor drone on about the benefits of statins—only to find out later that his teacher had been paid by 10 drug companies, five of which made the cholesterol treatments he’d been advocating. Then came the Pfizer photog.

Such incidents haven’t just embarrassed Harvard, though. They’ve also put the institution at the center of a national debate over the relationship between pharma and medical schools. It’s a fight about ethics, prized research projects, and millions and millions of dollars, of course, but it’s also personal. With two of HMS’s highest-profile professors serving as standard-bearers for the opposing sides, an already-controversial topic has turned into a full-out battle of wills.

No other faculty member at Harvard has been as vocal a critic of the pharmaceutical industry as Marcia Angell. A pathologist and former editor in chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, she began raising the alarm in 2000, when she wrote in the NEJM that medical schools were becoming “increasingly beholden to industry.” Harvard, she noted, had long prided itself on its strict conflict-of-interest stance, but she feared it was “in the process of softening its guidelines” in a bid to keep researchers from defecting to institutions with more-lax rules.

Instead, the school settled on a set of policies that was stringent, if not the nation’s strictest. The rules, still in place today, put some limits on doctors but do not ban them from meeting with low-level drug reps. Doctors are allowed to own stock in businesses related to their specialties, but only $30,000 worth or less, and they can accept up to $20,000 in speaking and consulting fees per year from the companies. The problem is that Harvard’s affiliated teaching hospitals have their own guidelines, which don’t always match up with the school’s. The patchwork system means doctors often might misinterpret the rules or not know which ones they should follow.

Angell wants the school to simplify the matter by basically cutting all ties to drug makers. Doctors “should have no financial interest in companies whose products they are evaluating,” she argues. No stocks. No money for speaking or writing for industry forums. Drug reps shouldn’t be allowed on campus.

If there’s such a thing as an anti-Angell, it’s Harvard hematologist Tom Stossel, brother of libertarian journalist John Stossel. When Angell wrote an op-ed in the Globe several months ago, Stossel promptly penned a rebuttal in Forbes. When Stossel was invited to speak at a 2007 public panel on pharma influence issues, Angell blasted the choice, saying that to include him amounted to “standing the whole thing on its head.” The two are “matter and antimatter,” says one acquaintance. “Put them in the same room and the universe might explode.”

In fact, Angell and Stossel have been in the same room at least once. At what should have been a fairly dry meeting of the American Society of Hematology in 2002, they gave dueling talks. Angell spoke in broad terms about the “dissolving” boundaries between academia and industry; the fact that medical meetings had become “a massive trade show…with free goodies.” Stossel got more personal. “I don’t need to feel morally superior to drug companies,” he said. “Let’s object to sanctimony.” Today, in person, he’s even more barbed: When it comes to research credentials, he says, “I don’t even consider myself in the same universe as Marcia Angell.”

Like Angell, Stossel is well aware that Harvard physicians pull in a lot of money from drug companies. Unlike Angell, he sees that as a good thing. Stossel traces improvement in Americans’ health directly to breakthroughs funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Limit doctors’ interactions with that industry, he argues, and you limit the power of the market to drive innovation.

Stossel also argues that the various controversies concerning Harvard and Big Pharma are overblown. The Pfizer rep with the cell phone wasn’t plotting a corporate takedown of the student protesters; he was taking photos of a public event out of personal interest. The professor who didn’t reveal his links to cholesterol drugs wasn’t technically doing anything wrong; Harvard only now requires that doctors disclose conflicts of interest in all public venues, including classrooms.

Stossel even refuses to condemn Biederman, the child psychiatrist, though he won’t quite defend him, either. “The second you show me solid evidence that he should have backed off on some conclusion and didn’t, he’s toast,” says Stossel. “But I bet what [the ongoing investigation] will find is that he didn’t do anything wrong.” Besides, he points out, having one bad apple among almost 10,000 faculty members is a risk worth taking. “We have to tolerate some bad behavior if we want progress,” he says.

This past summer Stossel cofounded the Association of Clinical Researchers and Educators (ACRE), an advocacy group for doctor/drug company partnerships. It has been ruthlessly parodied—most notably as Academics Craving Reimbursement for Everything—but it has also attracted some followers, even among Harvard med students, some of whom say they’re uncomfortable with the protesters’ divisive stance. Angell’s acolytes are “a vocal minority,” says Vijay Yanamadala, a med student who sides with Stossel. “We all agree on more than we disagree.”

Harvard officials are betting that’s the case. This past spring, a 19-member committee handpicked by the HMS dean began meeting behind closed doors to figure out exactly what it is that most people agree on. (Neither Angell nor Stossel is part of the group.) In the next few months, the committee will publish a report prescribing how to address HMS’s relationship with pharma, essentially deciding how much influence the industry should be allowed to have over the school’s next generation of doctors. Plus, any new policy recommendation will likely have wide-ranging consequences: As Harvard goes, so go medical schools around the country.

So far, though, the committee is moving slowly. “It hasn’t found that there are big gaps in the current policy that need to be addressed emergently,” says a source who has knowledge of the group’s deliberations. “But it wants a policy that will last for the next 20 years.” Given that Harvard is going to be tangled up with Big Pharma for those 20 years in one way or another, a cautious approach will probably emerge. But that’s also sure to do at least one thing: continue to outrage both Angell and Stossel.