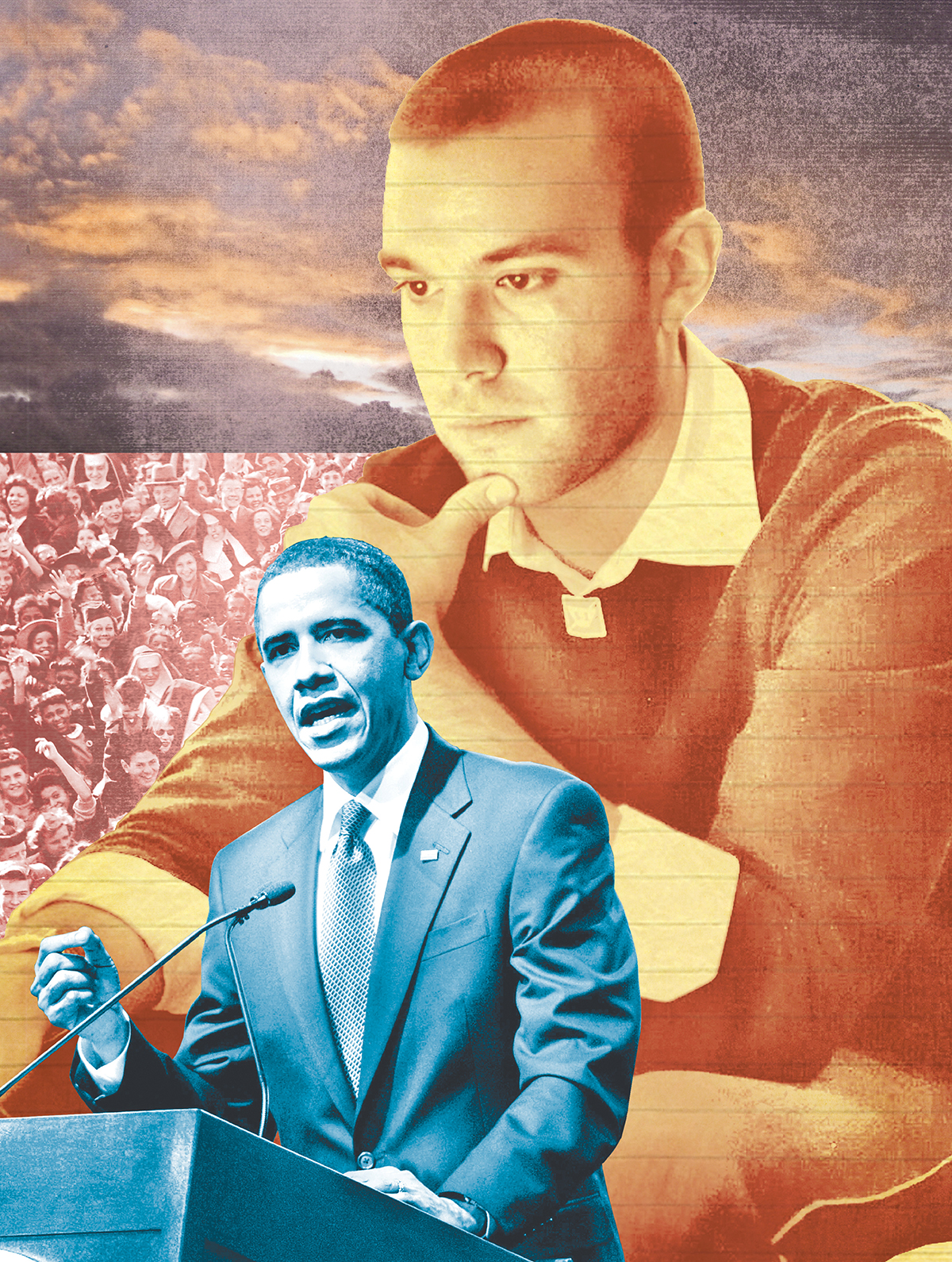

Obama’s Ghost

Illustration by Gluekit

“Hey, everyone, this is Jon Favreau, director of speechwriting.”

It’s mid-November and Barack Obama has begun his first official Asian tour with a speech at Suntory Hall in Tokyo. The president is discussing the importance of Asia as a trading partner. He mentions the specter of North Korea and the rise of China, of engaging the latter in talks on trade and human rights issues. And, as he almost always does, Obama talks a little about himself—calling himself the first Pacific president, thanks to his Hawaiian birth and his childhood stint in Indonesia.

Favreau isn’t in Suntory Hall, though. He’s across the street, in the lobby of the Okura hotel, where a White House videographer has corralled him, stuck him in front of a potted bonsai tree to talk about the speech for the White House website. “It’s my first time in Japan,” says Favreau, looking a little puffy and jet-lagged. In fact, in his suit and tie, with the bad lighting and straight-on camera angle, Favreau looks like a hung-over groomsman who’s been asked for a testimonial by the wedding videographer.

“The speech,” Favreau continues, “was written over the last couple of weeks. Terry Szuplat started it at headquarters.” Then Favreau and foreign-policy specialist Ben Rhodes stepped in, writing and editing it on the plane to Japan. “Some people stopped [at a refueling point] in Alaska, got out, hung out there,” he says. “But we stayed on the plane and had a group editing session where people sat around a table, went through the speech line by line, and told us what they liked and what they didn’t.

“So that’s always real fun for us.

“The president edited it after that, had a few line notes, which I’m holding right here,” he continues, waving a clump of manuscript papers in front of the camera. “And then we sent it off and it was done.”

And with that, he signs off. The video lasts less than two minutes, yet it offers what has been the most detailed account to date regarding the nature of Favreau’s work for Barack Obama.

Outside the Obamas’ marriage, perhaps no White House relationship has been the source of as much fascination as the president’s bond with his head of speechwriting. Some of it has to do with Favreau’s youth, of course (he’s 28), and some of it has to do with Favreau’s physical appearance. He looks less like a guy who works in the White House basement than a cast member of Entourage.

But a large part of the Favreau fervor is due to his central role in the Obama narrative. Obama’s appeal as a candidate was almost inseparable from his gifts as a talker. Unlike in most presidential campaigns of the past 25 years, in fact, the most memorable moments of the race came from speeches, addresses written at least in part by one Jon Favreau of North Reading, Massachusetts: the victory speeches in Iowa, the address in Berlin, the race speech in Philadelphia, the acceptance of the Democratic Party nomination in Denver.

By the time the campaign was over, Obama had been lauded as the most powerful and effective political orator in a generation, and Favreau, the president’s chief ghostwriter, his “mind reader” (as Obama calls him), had become a Washington celebrity. During the campaign, the New York Times and Newsweek profiled him; the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and others came calling soon after. He became fodder for political and gossip blogs. He not only appeared in a movie (the HBO documentary By the People: The Election of Barack Obama), he’s also reportedly dated a movie star.

From the first moments of his notoriety, though, Favreau has faced the problem of any good ghostwriter: trying to hide in plain sight. The man who speaks the words is supposed to get the credit. And with Obama, plenty of credit was due. A former president of the Harvard Law Review, Obama had made serious attempts to write fiction, penned a memoir that would go on to become a bestseller, and launched his career in national politics by giving a speech—the keynote address at the 2004 Democratic Convention—he had written himself.

That sort of résumé makes Favreau’s job simultaneously “the worst and the best job in political speechwriting,” as one writer put it. Less than a year in, it isn’t getting any easier: healthcare; Afghanistan; Wall Street; 120,000 troops still in Iraq. And though this month’s State of the Union address may be able to present a rosier picture of the economy, it will be delivered to a nation in which one in 10 workers doesn’t have a job.

There is something else, too. Call it the Hillary Prophecy. In early 2008, after Obama had pulled off the stunning victory in Iowa and the battle moved to New Hampshire, Clinton borrowed a phrase from former New York Governor Mario Cuomo. “You campaign with poetry,” Clinton said, “but you govern with prose.” At the time, Clinton was trying to defend her own speaking style, her lack of rhetorical flourish. But it was also a clear indictment of Obama, the first time an opponent had pointed out that the man’s greatest asset—those words, that speechmaking—could also be a liability.

As the administration enters its second year, that critique has become increasingly common. Peggy Noonan, the Wall Street Journal columnist and former speechwriter for Ronald Reagan, has written that Obama had grown boring. “And it’s not Solid Boring,” she wrote, “which is fine in a president and may be good. It’s sort of Faux Eloquent Boring.” It wasn’t just philosophical opponents making such assessments.

At a seminar at Harvard’s Kennedy School in October, Ted Sorensen, JFK’s legendary ghostwriter, also chided the new president. “I think that [Obama is] a remarkable speaker,” Sorensen said, “but his speeches are still largely in campaign mode.”

By the time of the November elections, when Obama unsuccessfully stumped for incumbent Democratic governors in New Jersey and Virginia, the idea had surfaced in the pages of the New York Times, the ultimate arbiter of conventional wisdom. “The limits of rhetoric were on display last week when the president could not rescue two foundering candidates in governor’s races,” writer Peter Baker observed. “Has Mr. Obama lost his oratorical touch?”

It seems appropriate that a president who wanted to be a writer would choose a speechwriter who wanted to be a politician.

The Favreau family settled around Manchester, New Hampshire. The patriarch, Robert J. Favreau, was elected as a Republican to the state legislature. One of his sons would become the Manchester chief of police. Another, Mark Favreau, met a pretty schoolteacher from Woburn named Lillian DeMarkis, and moved to Boston to marry her and start a family. Their first son arrived in 1981, and they named him Jonathan.

From early on, it was clear that the kid was precocious with language. “My mother,” Jon Favreau says, “loves to tell embarrassing stories about me reciting ‘The Night Before Christmas.'” That’s when he was two.

Photograph by Pete Souza

And politics was part of his early years. His mother’s family was Greek, and Michael Dukakis’s run for president in 1988 galvanized her. In 1992, Favreau, not even a teenager yet, stayed up late and watched all the presidential debates with his father.

When it came time to pick a college, a good friend said he was going to College of the Holy Cross, so Favreau applied, too, and received an academic scholarship. It was while in college that politics really began to entrance him. He took all the political science and sociology classes he could. “The whole gestalt of Holy Cross is how I think about politics,” Favreau says, “which is that it’s the art of the possible. We can all come together and talk about our differences. We can all come together in the fact that we need to help our community.”

Favreau volunteered to help advocate for welfare recipients in Worcester. The experience “left me wondering,” he would say, “why I would regularly encounter single working mothers who could not afford food, housing, or medical care, despite the fact that they worked over 40 hours a week. If the idea was to get people off welfare rolls and into jobs, why were the jobs failing to provide even the most basic standard of living? These questions led me to Washington.”

He got there in 2002, his junior year, when he was named one of the 32 Holy Cross students who would work in an internship program in DC. That spring, Favreau was assigned to the press office of Senator John Kerry, where he quickly made an impression. When Gary DeAngelis, the Holy Cross professor who ran the program, traveled to Washington to check in on the interns, Kerry aides pulled him aside. “They said, ‘This Favreau kid is really incredible,'” DeAngelis remembers. Among other things, the 20-year-old Favreau had helped ghostwrite several newspaper op-ed pieces that appeared under Kerry’s name. “Our students do significant work—not just answering telephones and photocopying,” DeAngelis says. “But this was pretty unusual. In 22 years running the program, I never saw anything like that.”

That fall, Favreau went back to Worcester for his senior year. He eventually won a prestigious Truman Fellowship and was picked to give the college commencement address, his first big speech.

That speech is now available through the Holy Cross website, a fact that seems to flummox the writer (“I never thought anyone would see that ever again”) and earned him some teasing from colleagues. It is a good speech for a college student, at once respectful and witty, sentimental and sincere without a hint of treacle. In the address, Favreau makes clear that he had been seduced by his time in the capital. “I loved the excitement,” he said, “the heated political debate, and meeting all those famous people—senators, Supreme Court justices, and those esteemed political-talk-show hosts who relieve their guests of the burden of finishing their own sentences.”

Though his speech would focus on the noble notion of making a difference in small ways—on the local school board, through volunteering—Favreau had a bigger vision for himself. “Somewhere along the way,” he told his classmates, “I made up my mind that one day I would return to that city as an elected representative.”

He wasn’t away for long. After graduating, he landed a job with Kerry’s campaign press office, which was in presidential campaign mode. At first he simply compiled news summaries, but an opportunity appeared quickly. “It was a dark moment in the Kerry campaign,” remembers Andrei Cherny, who’d been a speechwriter for Vice President Al Gore and became a Kerry policy adviser and the campaign’s director of speechwriting. Howard Dean had come out of nowhere and looked as if he would push Kerry out of the race. There were lots of defections. “We needed a full-time speechwriter,” Cherny says, “and we had a hard time finding someone to jump on board.”

Favreau, who then worked in a cramped office with Cherny, had given him that Holy Cross commencement speech as a joke. Cherny thought it good enough to earn Favreau a promotion. He told him, “Okay, you’re going to be assistant deputy speechwriter.” By the end of the campaign, Favreau was Kerry’s chief speechwriter.

But John Kerry was no Barack Obama. And after a bruising and bitter campaign, Favreau found himself unemployed and pissed off, wondering if he should leave Washington. “The Kerry campaign had beaten him down,” says DeAngelis. “He was fed up with whole scene, and ready to leave Washington and go back to grad school. It was interesting listening to him talk—someone so young who’d become disenchanted so quickly.”

Time hasn’t softened Favreau’s feelings about 2004. “By the end there was so much infighting, backstabbing—so much crap. And I was thinking, ‘This system does not work.’ The fact that we could lose based on what really seemed [to be] small stuff that was blown up.

“Obama,” he says, “was so much different.”

One night last winter, after he had moved back to DC once again—after he’d worked on Obama’s inaugural address, and the president’s first speech to the joint session of Congress, and many other smaller, more routine policy announcements—Jon Favreau closed up his office in the basement of the White House and met me for dinner. It had been a hard date to schedule. Partly because of his work commitments, but also because he felt he’d already been written about enough. He’d been the subject of a number of newspaper profiles, and had even been chosen runner-up in a “White House’s Hottest” contest sponsored by the Huffington Post. He’d agreed to meet only because my assignment then was to write about him for his college alumni magazine. (When I approached him about this story, Favreau sent me a friendly and polite e-mail, saying, in part, “I think I might pass…I’m trying not to do too many of these.” He didn’t respond to any subsequent e-mails or phone messages.)

We met at a new and noisy Latin American restaurant a few blocks from the White House. The president was out of town, taping an interview with Jay Leno in Los Angeles. Favreau ordered a mojito and took out a couple of BlackBerrys, which supplied him with periodic progress reports on Obama’s Tonight Show appearance. “It seems to be going pretty well,” he said, after checking one message.

That night, Favreau was a few months from his 28th birthday and seemed to be in the midst of growing up very quickly. He’d achieved the proximity to power that had so entranced him back in college. Almost every day, he spent time in the Oval Office. He was now in charge of a team of six speechwriters, which meant he’d traded in the jeans and sweaters of the campaign for a conservative suit and tie. After two years of living with six people in Chicago, he’d bought a condo near U Street, an area that was fast becoming a sort of subdivision of the subcabinet, home to myriad Obama officials. “DC can get very small very fast,” he said.

He learned that lesson the hard way. Not long after he had returned to Washington, Favreau went home to North Reading to visit his parents, who threw a party for him one night. At some point during the evening, a life-size cardboard figure of Hillary Clinton was brought out, and one of Favreau’s friends snapped a picture of him seemingly fondling the effigy of his former opposition. The picture ended up on Facebook, of course, and from there it quickly made the rounds. The New York Post‘s headline: “Barack Writer a Grope-a-Dope.” Then the bloggers piled on, questioning everything from Favreau’s maturity to whether the picture portended sexism in the Obama administration.

“I’m sure you’ve seen the Facebook thing,” Favreau said to me, after I’d spent a long time not bringing it up. “It was a good lesson. I got very lucky that it was that and nothing else. I wasn’t drunk; I was at my parents’ house. But it could have been in some bar. I’m not a wild partier. But it’s crazy that you have to be so careful.

“And it’s not good enough to say, ‘I’m a good person.’ It doesn’t matter. They’re just looking for anything. And as someone who’s been in this business for a long time and seen [this kind of scrutiny] happen to other people—you really don’t know until it happens to you how enraging it can be.

“You learn it comes with the territory. You learn to be careful.”

The rarefied air Favreau travels through now makes him class-A gossip fodder, and the fact that there is little dirt to be found on him doesn’t stop the press from digging to find it. Everything from his salary (a comfy $172,200, on par with chief of staff Rahm Emanuel) to his movement around Washington is newsworthy. Soon after he moved into the West Wing, Gawker reported he was dating someone else in the building, an aide named Ali Campoverdi, a Harvard graduate and former reality-TV star who also happened to be better-looking than anyone who’s ever appeared on Meet the Press. There were even some old pictures of her in sexy lingerie from a shoot for Maxim magazine. In the spring, the gossip sites would buzz with reports that Favreau had hooked up with another Harvard gal, actress Rashida Jones, the daughter of music mogul Quincy Jones and Mod Squad beauty Peggy Lipton. There were reports of the couple together at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner and making out at a bar in Georgetown, and eventually this “sighting” by the New York Post: “Rashida Jones, of NBC’s Parks and Recreation, with current beau Jon Favreau, President Obama’s whiz-kid speechwriter, in the lobby of Favreau’s swanky DC apartment building, the Charleston.”

When it came time to choose a date for the gala celebration of Time‘s “100 Most Influential People” issue, where he was listed along with Rush Limbaugh and Oprah Winfrey (prompting a friend to inform him, Favs, you have totally jumped the shark), Favreau picked someone gossip-proof: his mother. Lillian Favreau says her son is trying hard to keep his private life out of the public eye. It’s true she never thought his political career would lead to his dating movie stars. “But after all,” she says, in true mom mode, “he is very handsome.”

Somewhere between White House Hunk and Poetic Policy Wonk is the core of Jon Favreau, a guy who hasn’t been afraid to worry aloud (in that first New York Times profile) about losing his bearings. Andrei Cherny, his former boss, says, “I really think Favs is a once-in-a-generation talent—not only because of his intelligence or his fluidity with words, but because he’s a normal person. A lot of people in the political world are not. He’s able to connect with real people.”

During our dinner, Favreau said nearly the same thing about his boss. “With Obama, you think it’s almost like he’s so great because of his regularness. This is a guy who thinks like us, like regular people do. He approaches things in a commonsense sort of way. He constantly says things and you think, ‘Yeah, that’s it!’ And he’s genuine and very nice.”

It’s naive to take that statement at face value, coming from a young staffer about his boss, the man who happens to be the president. But there is something about Favreau that makes you wish you could. When I asked his mother why he’d decided against elective office for himself, she said, “Jon is an emotional-type person. Very honest and very sincere…not that there aren’t sincere politicians out there, but you have to have a real tough shell. Jon may not have that now, but you never know, in a few years….”

Favreau told me that his biggest concern was to not get bogged down in the day-to-day partisan pettiness—”the crap you hear on TV, the issue of the day.” Then he talked about reading Robert Kennedy’s speeches and how he admired their “riskiness,” their expansive sense of talking to “the conscience of the country.”

That is all well and good, of course, but Robert Kennedy never got a chance to govern. Governing is messy, something Favreau and his colleagues are learning on a daily basis. In September, Obama gave his speech on healthcare reform before the joint session of Congress, which would be remembered not for an Obama/Favreau line, but for two words shouted by South Carolina Congressman Joe Wilson: “You lie!”

“There were so many times in the Obama campaign when people said we were dead,” Favreau told me. “And since the administration started, we have been getting beaten up in the press from time to time. The crap of politics that I saw during the Kerry campaign is still there, but Obama was able to rise above it.”

Favreau had packed up his BlackBerrys and was ready to head home. “It’s going to be a tough road ahead,” he said, probably more prophetically than he would have wished. “Obviously it’s going to be harder to govern than it was to campaign.” Then the ghostwriter borrowed someone else’s famous phrase. You campaign with poetry, he said, but you govern with prose.