Designing the Dream

Deborah Hawkins expects a lot from a house. A good design, she believes, can be a source of endless amusement. It should engage people throughout the year, its beauty shifting with the light and seasons. It should be versatile, providing a unique space for every mood. So when it came time to build a dream residence of her own, the local musician, dancer, philanthropist, and art collector wanted nothing less than a customized masterwork. Her request: a design that was outwardly simple yet amazingly complex. A space that could accommodate frequent large parties without losing its sense of intimacy and wonder. And a layout that would offer plenty of display area for her growing collection of international and local art. “It’s important to support emerging artists and to encourage them,” Hawkins says. “To let them know that there are collectors right here in their backyard who value their work.”

Needless to say, Andrew Cohen, Thomas White, and Daniel Kasmarek of Andrew Cohen Architects have had easier clients to please. Luckily, the firm knew what it was getting into: Prior to embarking on her ambitious home project, Hawkins had hired the team twice before. In 1991 she had them add a 900-square-foot dance room onto her midcentury modern house in Belmont, and 10 years later, they designed a building for Springstep, her nonprofit music and dance center in Medford. As the Springstep project was winding down, Hawkins happened to notice proposals for White’s own house on his computer screen. Quirky, modern, and boxy, his concepts captivated her. “I’m going to look for some land,” she announced.

Meadow Views: Deborah Hawkins and her English cocker spaniel, Cooper, stroll through the living room, outfitted with B & B Italia sofas from Montage. / Photograph by Greg Premru.

One morning in 2005, she called White to inform him that she’d found the perfect site for a new undertaking: a nine-acre former Christmas tree farm in Lincoln. The property posed challenges, however. The tightly planted pines towered 70 feet overhead; there was a bluff on one end of the parcel; and the rest of it was covered by wetlands, leaving only a few buildable sections to work with.

The architects’ first proposal was a series of sprawling split-level boxes dug into the hillside. Once fully detailed, though, that turned out to be too expensive to build. Their second design was the antithesis of the first: a single box, wrapped in reflective glass, with a huge hole through the center. “I think that scheme was too extreme,” White says. “Too high-tech, too radical for Deb.”

Sculpture Park: The entry deck features two pieces by Boston-based artists: a copper and bronze abstraction by Julie Levesque, and a resin and mica figure by Tory Fair. / Photograph by Greg Premru.

Then, in the second year of the design process, Hawkins married otolaryngologist George Kazda, who, as a native of Prague, added a European sensibility to the mix. She asked the architects to try again, this time with a little guidance from her partner. What emerged was, at last, a plan with the clarity Hawkins sought. “I’ve always found when you say, ‘Go back to the drawing board,’ it comes out better, more condensed, more concise, more concentrated,” she says. And the result of her perfectionism was a home that left Hawkins, Kazda, and the design team as proud as can be.

As built, the structure offers two completely separate experiences: one for visitors, and one for the owners. In just the first taste of the house’s many whimsical features, guests arrive on the second level via a bridge from the upper parking lot at a massive deck, which sits in the shade of a cantilevered room overhead. A curious parade of shadows, perspectives, and light emerges as visitors move through the space. A cutout skylight illuminates the front door; once you pass through the entry, an interior courtyard becomes visible across the hall. Below is an outdoor sculpture court. Guests promenading down a glass-railing staircase to the living room are treated to views of courtyards, decks, and skylights. The procession of scenes showcases the building’s enigmatic nature. “It’s a giant, complicated wooden box that results from marrying circulation, site, voids, and cuts,” White says. “And here is one place you can really experience that.”

Party Ready: When guests arrive, Hawkins can conceal the kitchen with a floor-to-ceiling curtain. / Photograph by Greg Premru.

What’s more, Hawkins and Kazda are able to enjoy a more-intimate interaction with their home when they feel like it. They can pull into their three-car garage on the ground floor, walk through an extended mudroom (which includes a washing station for their English cocker spaniel, Cooper), and then slip behind the kitchen and up the back stairs to the master suite, bypassing the dramatic front entry and entertaining spaces. Beyond their dressing area is access to a private sleeping porch, which overlooks a wildflower field. Experienced this way, the 6,995-square-foot abode feels like a home one-third the size.

The property’s multiple exterior spaces take on different moods depending on the season and the time of day. In the morning, Hawkins and Kazda enjoy sitting in the living room as the sun comes around. In the afternoon, they take in the light from the screened porch off the TV room. “We sit there a lot, looking straight out toward the woods,” says Hawkins. “It’s cozy, but still outdoors.” The house was also designed to be as eco-friendly as possible, with bamboo flooring, a double exterior wall that has 12 inches of insulation, and heating and cooling provided by a geothermal system that taps into the ground water via a deep well.

More than just a house, the project is a symbol of Hawkins’s dedication to the arts. She spent years building her collection of works by local painters and sculptors. And now she finally has an architectural tour de force in which to showcase them.

Collection Highlights:

1) A poured-abaca and gouache installation by Acton-based artist Michelle Samour brightens up a second-floor hallway.

2) A ceramic flower piece by George Alexander hangs above a mosaic-tiled sideboard by John Eric Byers in the living room.

3) Cole Morgan’s joyous yellow painting accents a wall adjacent to the kitchen.

4) A matching painting and console table by Randy Shull provide a perfect showcase for offbeat knickknacks.

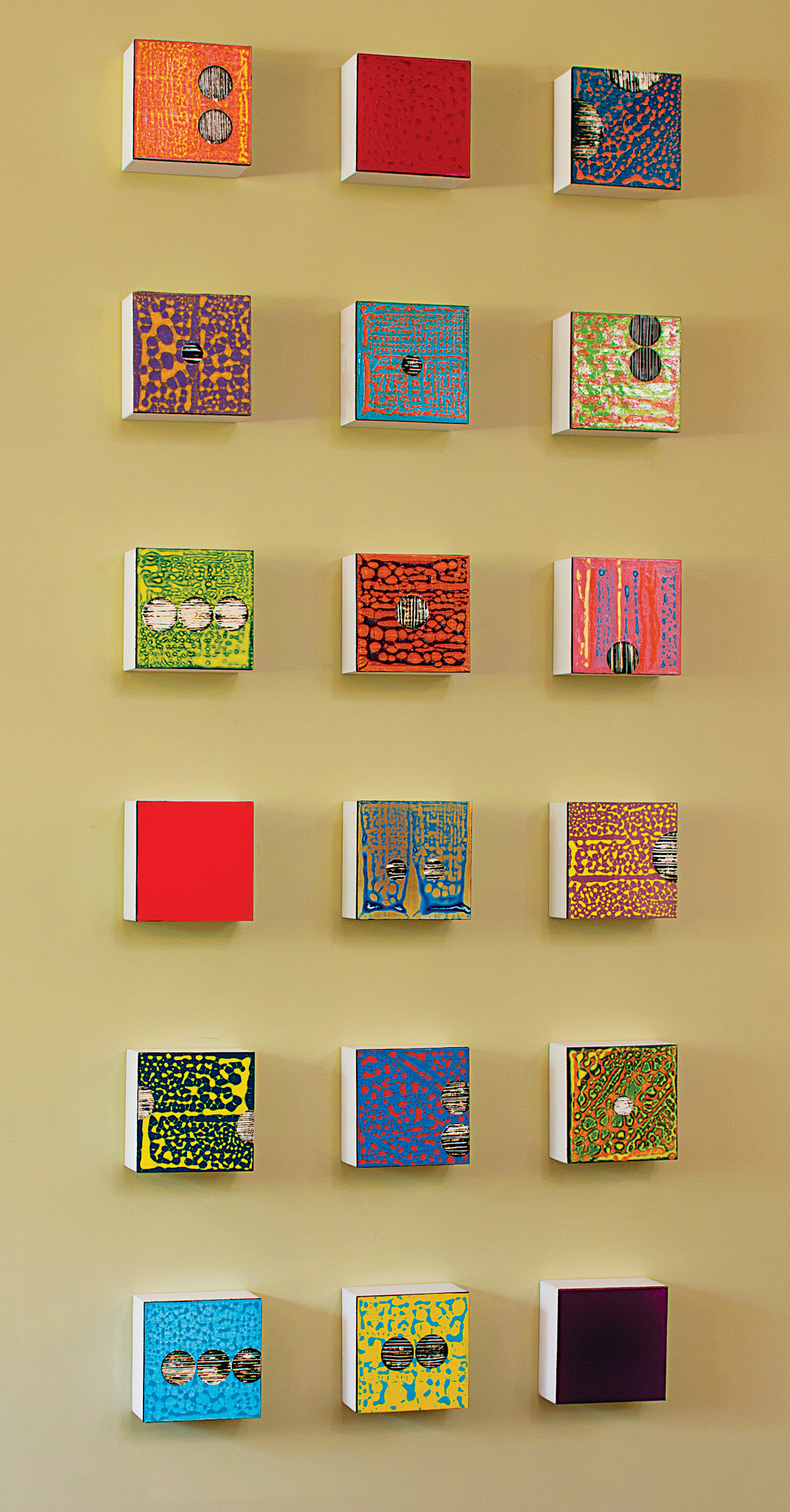

5) Charming mini canvases by Canadian artist Marie Lannoo create a focal point at the base of the main stair.

6) A striking ceramic bust by Peter VandenBerge keeps watch over the landing that leads to the master bedroom suite.