10 Questions with Landscape Architect Mikyoung Kim

Chongae Canal was made with materials from all nine of Korea’s provinces. Photo by Robert Such.

From backyard fences to massive public spaces that temporarily unite divided governments, landscape architect Mikyoung Kim has a unique vision that creates community and encourages the use of senses for every project.

After an injury sidelined her piano studies in college, she went on to get her master’s at Harvard Graduate School of Design and taught at Rhode Island School of Design, where she is now a Professor Emeritus. Her work worldwide recently earned her accolades from the American Society of Landscape Architects, which named her to its Council of Fellows for 2014. But Kim says the most rewarding praise comes from those who engage with the work of her Allston-based team at Mikyoung Kim Designs—touching, smelling, hearing, and yes, taking selfies at these projects around the world.

1. What’s your definition of success?

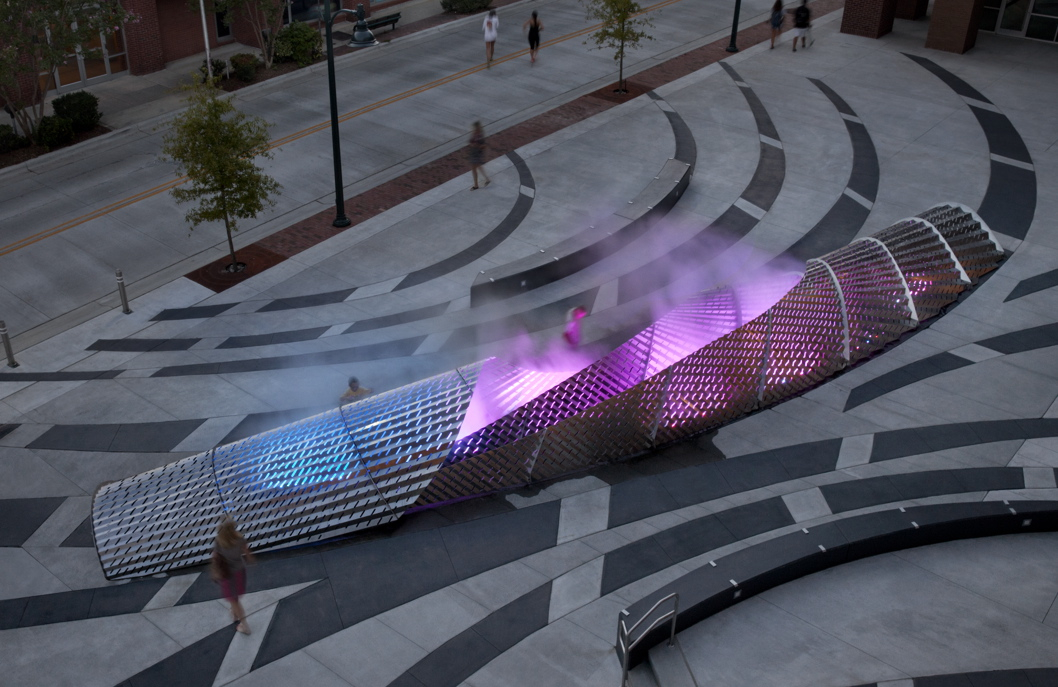

A skateboarder sent us a series of action photos at one of our projects, the “Exhale” sculptural mist fountain (photo below). Selfies are these huge identifiers for us when people want to show us how they’re engaging with the place. That’s really rewarding for me, to know people who weren’t part of the day-to-day process of design “get it,” engage in it, and appreciate it.

2. There are some wonderful shots like that from your ChonGae River Canal Restoration Project in Korea—do you find it reminiscent of WaterFire in Providence, where you taught for many years at RISD?

It’s very much like Providence, where people use it as a gathering space, and both projects transformed the city. We collected stone from multiple quarries around the nine provinces from North and South Korea, and created nine source points through these nine different stones. The idea was that these two separate countries could in the future come together and work together…so the material itself was meaningful but also the process was meaningful—the South Korean government reached out and got these stones from North Korea.

3. Did you feel a special connection to the Korean project, since both of your parents emigrated from there?

Even though I was born here and I’m an American citizen, I grew up at a time when there weren’t many Asians where I was living (Hartford, Connecticut). People tell me I have an uncanny ability to go to a new place and really listen or hear and understand what that place is about.

4. That must help you a lot in your career…

When I go work in Abu Dhabi or Qatar, I feel like everything seems fresh and special and I can bring a new appreciation for the familiar. When my son, Max, first saw a dandelion turn from yellow to those little white tufts, he could just not believe it…for us it’s like, “It happens all the time,” but when you see somebody else get excited it makes you realize, that’s interesting, that is cool.

5. How has being a mom changed your design aesthetic?

I think that being a parent is about developing daily rituals. I’m always interested in the challenges of somebody who sees one of our landscapes 600 times a year. How do we engage them on a daily level or a seasonal level? There’s that kind of notion of engagement—how do we celebrate seasonal interests from summer mist fountains, to winter ice skating rinks?

6. You could live anywhere in the world—why are you still in Boston, and what is the design aesthetic of your own space?

This landscape and the seasonal changes is what I really know and love…the snow and the changing of the leaves…this landscape is like coming home. During the work week I live in a Brookline brownstone townhouse, it’s very vertical with floor-to-ceiling windows. On the weekends and during summers in Rockport, we have more of a vintage-meets-modern house. I have a very small urban shade garden, and a more expansive waterfront garden. They’re kind of outdoor laboratories where I try out different plants and planting patterns and see how they work.

7. Do you like designing for all seasons?

We always do artistic renderings of a project in all seasons…Like the Flex Fence in Lincoln (photo below), that’ a project where we really thought about what that landscape would look like throughout the seasons. It’s woven into this native landscape as a tapestry but in the winter it becomes the star, when the entire landscape is white.

8. You’ve said that metal is a favorite material of yours to work with—but many people think of it as more cold and unemotional.

I actually don’t think of metal as a rigid material because it can bend, you can melt it, heat it, form it, mold it, cut it, perforate it. But I understand that certain kinds of metal have a quality some people would say lacks warmth because of lack of shininess. Now we’re doing a project in Portland, Oregon, collaging different kinds of metals into a kind of quilt–copper, steel polished, stainless–creating a gateway with that.

9. How did your early beginnings with music influence your career in the visual arts, and what you like to call multi-sensory experiences?

I have this condition, it’s very mild—synesthesia. Sometimes when I close my eyes and hear music, I actually “see” color…I think naturally I merge the senses, they’re not separated. With the landscapes we design, we’re trying to say it’s not like a museum. We would like to put signs everywhere to say “Please touch, and smell, and listen, and close your eyes.”

10. What are the greatest lessons you’ve learned as a professor, and now working on a team at Mikyoung Kim Designs?

Teaching really taught me to love engagement and learn that other people have these ideas that can open a door in your mind. I think that my studio is very much like a studio in school in that we try to practice the open engagement of ideas. It’s really a healthy reminder for designers to have young people around that keep your ideas fresh, so the mind is limber. I think it’s every easy for designers to become predictable or stale and that’s probably my biggest fear.

For more information, contact Mikyoung Kim Design, 119 Braintree Street, Suite 103, Boston. Info: 617-782-9130, myk-d.com.

See more for Mikyoung Kim, below.

The “Exhale” sculpture in Chapel Hill, NC emits mists and changes hues. Photo by Mark La Rosa.

The outdoors come indoors at the Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago. Photo by Hedrich Blessing.

Mikyoung Kim’s flex fence at a private residence in Lincoln. Photo by Chris Baker.